When Any Job Isn't Enough - Mary Reynolds Babcock Foundation

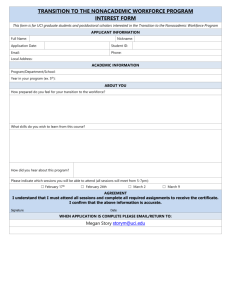

advertisement