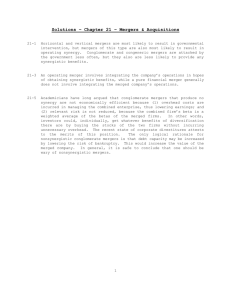

Effective Mergers and Acquisitions

advertisement