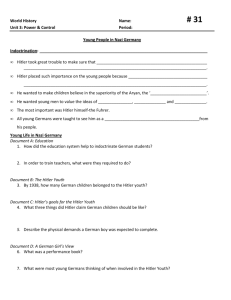

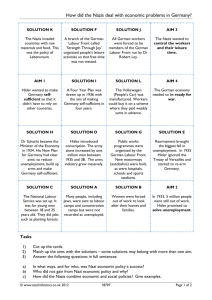

5. Conformity and Obedience - Facing History and Ourselves

advertisement