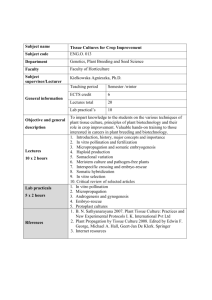

an in-depth look at the vitro bankruptcy proceedings

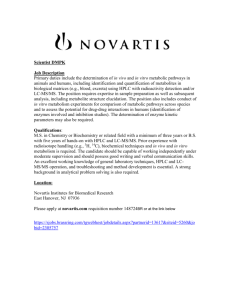

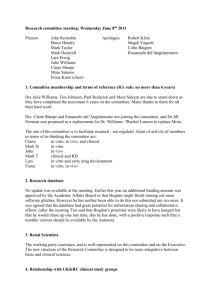

advertisement