PDF - Scottish Left Review

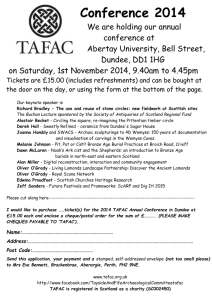

advertisement