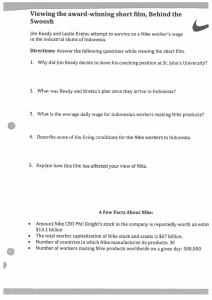

How Does This Idea Play Out In Reality Behind Nike`s Logo

advertisement