Happy accidents: the making of a marvellous man

advertisement

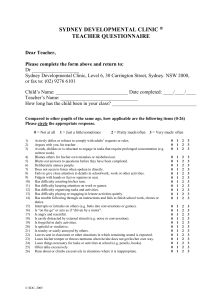

Happy accidents: the making of a marvellous man philosophy Lord (Robert) May interview and photography: Alison Muir I n a recent speech to policymakers in Berlin, world leader in mathematical biology, Australian-born Lord May of Oxford (BSc ’57 PhD ’60) said: “Small actions now are disproportionately important. They are more important than bigger actions later because of the non-linearity of the process we are talking about.” What he and the policymakers were talking about – and what Australia is talking about with renewed vigour since the ratification of the Kyoto Protocol – is climate change. Lord (Robert) May – “call me Bob” – whose first choice of title for his 2001 life peerage was Lord May of Woollahra (vetoed by Australian government protocol, sadly) has made deceptively simple yet potentially world-shaking pronouncements the habit of a lifetime. President of the Royal Society of London from 2000-2005, former chief scientific adviser to the British Government and a professor at Sydney, Harvard, Princeton, Oxford and the Imperial College, London, Lord May graduated from the University of Sydney in 1959 with a doctorate in theoretical physics. Chemical engineering had been his original choice but as he pointed out in November 2007 when he delivered the keynote lecture at the Lowy Institute (he sits on its advisory committee), his life has been “a series of accidents.” “I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do when I left Sydney Boys’ High,” says May. “The careers advisor said I should be a lawyer as we had a rather good debating team, and my family wanted me to do medicine. However, I had a very influential science teacher and it was partly because of him – and because I wanted to do something practical – that I enrolled in first year chemical engineering.” Young Bob May loved puzzles and games and thought it would be “fun” to sit the same exams as his friends. History doesn’t record what they thought when he topped maths and chemistry and came third in physics. “I hadn’t studied for physics,” he says cheerfully but adds that he won a ₤100 prize – one contingent on him completing second year physics and chemistry. “The sheer accident of that meant I studied second year chemical engineering and physics.” He “did pretty well”. By third year, May decided to major in pure maths, applied maths and physics. “Then the people in [the School of] Physics were very keen that I do the Honours year and that’s how it happened.” Science is fun Bob May lecturing at the Harry Messel International Science School, circa 1971 26 SAM Spring 08 May is convinced that anyone planning to study science should want to do it because it looks like “fun”. This was exactly how he viewed his chance to work with eminent Canadian-born physicist Harry Messel, then running the School of Physics. “Sydney University was an extraordinary place to be in the 1950s,” he says, recalling how Messel, one of the first to seek research funds from corporate and private sponsors, ended up in a poker game with Sir Frank Packer and other potential donors. Not long into the game Messel was dealt a royal flush but instead of scooping the pot, he kept his mouth shut and quietly discarded the winning hand. “He thought it would not be very helpful if he won,” May reports with an impish grin. At the time, “Harry and his mates” were working on the hot topic of superconductivity and were having such a good time that May decided to join in the fun and do his PhD in theoretical physics. One of Messel’s “mates”, Robbie Schafroth, became his PhD supervisor. When Schafroth was offered the foundation chair at the University of Geneva, he asked May to join him as his assistant. A short time later, however, Schafroth was killed in a plane crash. May took off for Harvard to do a post-doctorate. It was while at Harvard that he met his wife, Judith, and with his post-doctorate under his belt, the pair flew home to Sydney. They married in the summer of 1962 and built a house in Lane Cove. For the next 10 years May was Professor of Theoretical Physics at Sydney University. Animal dynamics Drawn to Charles Birch, the main figure for founding social responsibility in science in Australia, May says it was during this time that he literally “blundered” into ecology. “I was trying to find out what I was being socially responsible about, when I read Ecology Resource Management by Ken Watt and began thinking about applying mathematics to ecological problem solving,” he says. Birch didn’t think “this theoretical stuff” would be of any use but rather than dismissing it out of hand, he suggested May talk to Princeton’s famous ecologist Robert H. MacArthur. “Again it was just an extraordinary lucky accident because this was at a time when some of those in ecology had begun to frame questions in the style of theoretical physics, such as the structure of the food web, or what determines the relative abundance of species within a community,” May remembers. “For example, why were there six species of warblers in the trees of Vermont and not 60 or just one.” MacArthur, he says, was a leader in framing these questions. “But none of them had the box of tricks to handle it,” he adds. None that is, until May came along. Rather than embark on an 18-month sabbatical to study astrophysics in Britain, May went to Princeton. Terminally ill with renal cancer, MacArthur, 42, had only a few months SAM Spring 08 27 He created the new biology field of “chaotic dynamics” to live. Within an hour of their meeting, he offered May the job as his successor. Thus, as a result of yet another “accident”, May became Professor of Zoology at Princeton for the next 16 years, where, using his skills in theoretical physics and mathematics, he created the new biology field of “chaotic dynamics”. By using mathematical modeling, May not only revealed the fluctuating dynamics of animal populations but contributed greatly to the formulation of environmental policies and how best to manage different ecosystems. “If you look backwards to the theory of evolution, there’s a wonderful phrase in one of Darwin’s letters in which he bemoans the fact that he didn’t have maths,” says May. HIV and AIDS Leaving the USA in 1988, May took up professorships at the Imperial College, London, and Oxford University, where he continued his research into mathematical biology, analysing the conditions under which viruses and bacteria affect host populations. The results he obtained impacted a broad spectrum of science in the public health sector, ranging from genetic research into disease carriers to strategies for dealing with parasites. In addition he investigated the spread of AIDS and offered effective proposals for policies to slow the spread of HIV, AIDS and other contagious diseases. “Ecologists like more romantic things – preferably things with fur and feathers – rather than looking down a microscope and thinking about diseases,” he says. “But my colleague, Roy Anderson, and I were interested in The Search For Please take 10 minutes to take the on-line Faculty of Science Alumni Survey: Scien ce Alum ni Did you graduate from the Faculty of Science at Sydney? What are you up to now? Science can lead you in so many different directions and it is always interesting to learn about the career paths and achievements of our alumni. I would like to find out more about our Alumni and how you would like to be contacted by the University and the Faculty. Would you like to know more about our outreach activities, your classmates and be invited to events? Would you be interested in mentoring current students or finding out more about the research and achievements of our scientists? www.science.usyd.edu.au/alumnisurvey Please complete the survey by midnight on 3rd October 2008 and have a chance to win one of four iPod Nanos! If you would like to know more about the survey or about our current range of activities please contact Trixie Barretto: trixie@science.usyd.edu.au In addition to this, our current and prospective students are always keen to know what a degree in science will mean to them in terms of preparing for an interesting career - I hope that feedback gathered by the survey will provide information about how a science training can be used to prepare for the wide range of careers in which we know our alumni are engaged. I encourage you to provide us with information through the survey and look forward to your feedback – it will assist me and my team to better understand the science student and alumni experience, enabling us to change or improve our services where necessary. Professor David Day, Dean of Science Professor David Day, Dean of Science 28 SAM Spring 08 The Faculty of Science the degree to which infectious disease might affect the numerical abundance and geographical distribution of animals and plants. That led us back to thinking about humans and their engagement with infectious disease.” May and Anderson published the world’s first estimate of HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa in 1991 but cautions that understanding the exact pathogenesis of HIV is still some way off. “We understand how individual molecules act, how the virus interacts with the immune system cells, and we can describe it at a molecular level. But we still don’t understand how lots of strains of HIV interact with lots of strains of the immune system cells. We are probably going to need to do this before we have a vaccine.” While many would regard the USA as the number one leader in science, May disputes this, particularly in regard to AIDS research. “Australia is one of the leaders here and from the beginning looked at the science and did not befuddle it with faith-based doctrinaire prejudices,” he says, citing the US government’s opposition to needle distribution programs and the distribution of condoms. It is more valid, he believes, to measure the health of ecosystems in conventional GDP terms Climate change From his own research as well as his work as Scientific Adviser to the UK Government from 1995-2000 and his time as President of the Royal Society, May is well aware of the problems facing the world from climate change, new and re-emerging diseases and the loss of biological diversity. “Ahead of us are dangerous times,” he warns. “Many of these threats are not yet immediate, yet their non-linear character is such that we need to be acting today.” Examining the different arguments put forward by conservationists in their bid to save various creatures from Above left: Lord May and Bob May above extinction, he dismisses claims that today’s flora and fauna are the raw stuff of tomorrow’s biotech industry. Instead he contends that in the future scientists will begin designing breakthrough medicines and biotech products from the molecule up rather than go bio-prospecting for them. It is more valid, he believes, to measure the health of ecosystems in conventional GDP terms. “Attempts are now being made to do this but we still don’t understand enough about how ecosystems are structured, how they function, or what happens when we take bits out of them or put new bits into them unintentionally,” he says. He quotes one of the founding fathers of the conservation movement, Aldo Leopold, who said that the first rule of intelligent tinkering “was to keep all the pieces”. May cites the 2001 United Nations-sponsored Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (www. milleniumassassment.org) which grouped ecosystem services under 25 broad headings to find out what sort of shape they were in. With five of the categories it was hard to say. With three associated with human food production, they had actually improved. Worryingly, however, the remaining 17 were all deemed to be in serious trouble. But while May believes this creates a compelling argument for stewardship, he points out that “stewardship is a motive that comes more comfortably with the luxury of the comfortable life. If you are someone struggling to feed your family in the developing world it may be a less powerful motive.” He pauses, then flashes a quick smile. “As a scientist, though, it is not a question of whether or not I care about these things. I work on the problem not out of some sort of motive to be a good person but simply because they are good problems.” SAM SAM Spring 08 29