"The Cult of Bebop"

advertisement

"The Cult of Bebop" i 155

Not play the melody. And then they're surprised they get thrown out and

have strippers put in their place.

BIGARD: Well, I don't know.

ARMSTRONG: Well, you oughta know, pops, you've been around long

enough. Look at the legit composers always going back to folk tunes,

the simple things, where it all comes from. So they'll come back to us

when all the shouting about bop and science is over, because they can't

make u p their own tunes, and all they can d o is embroider it so much

you can't see the design n o more.

MEZZROW: But it won't last.

ARMSTRONG: It can't last. They always say ':jazz is dead" and then they always come back to jazz.

Source: 'Bop Will Kill Business Unless It Kills Itself First'-Louis

"

Armstrong." Down Beat,

April 7 , 1948, pp. 2-3.

LIKE RAGTIME, HOT JAZZ, SWING, FREE JAZZ,

blues, rock, and rap-or, for that matter,

twelfth-century polyphony and Stravinsky's

Rite of Spring--bebop was initially attacked as

unmusical and immoral. Some jazz critics and

musicians condemned the new style, but more

damaging was the sensationalistic media coverage it received. With his beret, goatee, and

horn-rimmed glasses, Dizzy (John Birks) Cillespie (191 7-1 993) became the genre's icon.

Offended by popular conceptions of the music and its subculture, Cillespie devoted a

chapter of his 1979 autobiography, To Be, Or

..

Not. . . To Bop, to setting the record straight.

Cillespie had established himself as a

player in the big swing bands of Teddy Hill,

Cab Calloway, Earl Hines, Duke Ellington, and others; he later led a big band himself, where he experimented successfully with Afro-Cuban rhythms and percussion

instruments. But he is best remembered for his work in small combos, where he and

alto saxophonist Charlie Parker set new speed records for instrumental virtuosity and

musical imagination. One of the most influential trumpeters in history, Cillespie is

usually given chief credit, along with Parker, for developing the genre of bebop during the early 1940s.

In this chapter, Cillespie challenges eleven popular myths about bebop, minimizing the importance of fashions and drugs so that he can underscore the seriousness, artistry, and creativity of the music. Without abandoning the sense of hilarity

that won him his nickname, he explains the music's complex social context, where

strategies for operating in a racist environment included searching for African roots,

converting to Islam, and taking great pride in African-American heroes such as heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis or singer, actor, and black activist Paul Robeson.

31

"The Cult

of Bebop"

. . . To Bop (New York: Doubleday,

1979). excerpted from pp. 278-302 and facing p. 483

Source: Dizzy Gillespie with A1 Fraser, To Be, Or Not

A

round 1946, jive-ass stories about "beboppers" circulated and began

popping up in the news. Generally, I felt happy for the publicity,

but I found it disturbing to have modern jazz musicians and their

followers characterized in a way that was often sinister and downright vicious. This image wasn't altogether the fault of the press because many followers, trying to be "in," were actually doing some of the things the press

accused beboppers of-and worse. I wondered whether all the "weird" pu15i

licity actually drew some of these way-out elements to us and did the music

more harm than good. Stereotypes, which exploited whatever our weaknesses

might be, emerged. Suable things were said, but nothing about the good we

were doing and our contributions to music.

Time magazine. March 25, 1946. remarked: "As such things usually do, it

began on Manhattan's 52nd Street. A bandleader named John (Dizzy) Gillespie, looking for a way to emphasize the more beautiful notes in 'Swing,' explained: 'When you hum it, you just naturally say bebop, be-de-bop. . . .'

"Today. the bigwig of bebop is a scat named Harry (the Hipster) Gibson. who in moments of supreme pianistic ecstasy throws his feet on the

keyboard. No. 2 man is Bulee'(~1im)Gaillard, a skyscraping zooty Negro guitarist. Gibson and Gaillard have recorded such hip numbers as 'Cement Mixer,'

which has sold more than 20,000 discs in Los Angeles alone; 'Yeproc Heresay,' 'Dreisix Cents.' and 'Who Put the Benzedrine in Mrs. Murphy's Ovaltine?' "

The article discussed a ban on radio broadcasts of bebop records in Los

Angeles where station KMPC considered it a "degenerative influence on youth"

and described how the "nightclub where Gibson and Gaillard played" was

"more crowded than ever" with teen-agers who wanted to be bebopped.

"What bebop amounts to: hot jazz overheated, with overdone lyrics full of

bawdiness, references to narcotics and doubletalk."

Once it got inside the marketplace, our style was subverted by the press

and music industry. First, the personalities and weaknesses of the in people

started becoming more important, in the public eye, than the music itself. Then

they diluted the music. They took what were otherwise blues and pop tunes,

added .'mop, mop" accents and lyrics about abusing drugs wherever they could

and called the noise that resulted bebop. Labeled bebop like our music, this

synthetic sound was played heavily on commercial radio everywhere. giving

bebop a bad name. No matter how bad the imitation sounded, youngsters and

people who were musically untrained liked it, and it sold well because it maintained a very danceable beat. The accusations in the press pointed to me as

one of the prime movers behind this. I should've sued, even though the

chances of winning in court were slim. It was all bullshit.

Keeping in mind that a well-told lie usually contains a germ of truth, let's

examine the charges and see how many of those stereotypes actually applied

to me.

Lie number one was that beboppers wore wild clothes and dark glasses

at night. Watch the fashions of the forties o n the late show, long coats, almost down to your knees and full trousers. I wore drape suits like everyone

else and dressed no differently from the average leading man of the day. It

was beautiful. I became pretty dandified, I guess, later during the bebop era

"The Cult of Bebop" / 157

when my pants were pegged slightly at the bottom, but not unlike the modestly flared bottoms o n the slacks of the smart set today.

We had costumes for the stage-uniforms with wide lapels and beltsgiven to us by a tailor in Chicago who designed them, but w e didn't wear

them offstage. Later, we removed the wide lapels and sported little tan cashmere jackets with no lapels. This was a trendsetting innovation because it

made no sense at all to pay for a wide lapel. Esquire magazine, 1943, Arnerica's leading influence on men's fashions, considered us elegant, though bold,

and printed our photographs.

Perhaps I remembered France and started wearing the beret. But I used

it as headgear I could stuff into my pocket and keep moving. I used to lose

my hat a lot. I liked to wear a hat like most of the guys then, and the hats

I kept losing cost five dollars apiece. At a few recording sessions when I

couldn't lay my hands on a mute, I covered the bell of the trumpet with the

beret. Since I'd been designated their "leader." cats just picked up the style.

My first pair of eyeglasses, some rimless eyeglasses, came from Maurice

Guilden, an optometrist at the Theresa Hotel, but they'd get broken all the

time, so I picked u p a pair of horn rims. I never wore glasses until 1940. As

a child, I had some minor problems with vision. When I'd wake up in the

morning, I couldn't open my eyelids-they'd stick together. My mother gave

me a piece of cotton; someone told her that urine would he1p:Ever-y time I

urinated, I took a piece of cotton and dabbed my eyes with it. It cured me.

I read now without glasses and only use glasses for distance. Someone coming from the night w h o saw me wearing dark glasses onstage to shield my

eyes from the glare of the spotlights might misinterpret their meaning. Wearing dark glasses at night could only worsen my eyesight. I never wore dark

glasses at night. I had to be careful about my eyes because I needed them

to see music.

Lie number two was that only beboppers wore beards, goatees, and other

facial hair and adornments. I used to shave under my lip. That spot prickled

and itched with scraping. The hair growing back felt uncomfortable under

my mouthpiece, s o I let the hair grow into a goatee during my days with

Cab Calloway. Now a trademark, that tuft of hair cushions my mouthpiece

and is quite useful to me as a player; at least I've always thought it allowed

me to play more effectively. Girls like my goatee too.

I used to wear a mustache, thinking you couldn't play well without one.

One day I cut it off accidentally and had to play, and I've been playing without a mustache ever since. Some guy called me "weird" because he looked

at me and thought h e saw only half a mustache. The dark spot above my

upper lip is actually a callus that formed because of my embouchure. The

right side of my upper lip curls down into the mouthpiece when I form my

embouchure to play.

Many modern jazz musicians wore no facial hair at all. Anyway, we

weren't the only ones during those days with hair on our faces. What about

Clark Gable?

Number three: that beboppers spoke mostly in slang or tried to talk like

Negroes is not s o untrue. We used a few "pig Latin" words like "ofay." Pig

Latin as a way of speaking emerged among blacks long before our time as

158 / The Forties

a secret language for keeping children and the uninitiated from listening to

adult conversations. Also, blacks had a lot of words they brought with them

from Africa, some of which crept over into general usage, like "yum-yum."

Most bebop language came about because some guy said something and

it stuck. Another guy started using it, then another one, and before you knew

it, we had a whole language. "Mezz" meant "pot," because Mezz Mezzrow,

was selling the best pot. When's the "eagle gonna" fly, the American eagle,

meant payday. A "razor" implied the draft from a window in winter with cold

air coming in, since it cut like a razor. We added some colorful and creative

concepts to the English language, but I can't think of any word besides bebop that I actually invented. Daddy-0 Daylie, a disc jockey in Chicago, originated much more of the hip language during our era than I did.

We didn't have to try; as black people we just naturally spoke that way.

People who wished to communicate with us had to consider our manner of

speech, and sometimes they adopted it. As we played with musical notes,

bending them into new and different meanings that constantly changed, we

played with words.

Number four: that beboppers had a penchant for loose sex and partners

racially different from themselves, especially black men who desired white

women, was a lie.

It's easy for a white person to become associated with jazz musicians,

because most of the places we play are owned and patronized by whites. A

good example is Pannonica Koenigswater, the baroness, who is the daughter of a Rothschild. She'll be noticed when she shows up in a jazz club over

two or three times. Nica has helped jazz musicians, financially. She saw to it

that a lotta guys who had no place to stay had a roof or put some money

in their pockets. She's willing to spend a lot to help. There's not too much

difference between black and white women, but you'll find that to gain a

point, a white woman will do almost anything to help if it's something that

she likes. There's almost nothing, if a white woman sees it's to her advantage, that she won't do because she's been taught that the world is hers to

do with as she wants. This shocks the average black musician who realizes

that black women wouldn't generally accept giving so much without receiving something definite in return.

A black woman might say: "I'll love him . . . but not my money." But a

white woman will give anything, even her money, to show her own strength.

She'll be there on the job, every night, sitting there supporting her own goodies. She'll do it for kicks, whatever is her kick. Many white women were great

fans and supporters of modern jazz and brought along white males to hear our

music. That's a secret of this business: Where a woman goes, the man goes.

"Where you wanna go, baby?"

"I wanna go hear Dizzy."

"O.K., that's where we go." The man may not support you, but the woman

does, and he spends his money.'

'Here Gillespie echoes the author of "Here's the Lowdown on 'Two Kinds of

Women' "-but without the resentment! See "Jazz and Gender During the War

Years," earlier in this volume.

"The Cult of Bebop" / 159

As a patron of the arts in this society, the white woman's role, since white

males have been so preoccupied with making money, brought her into close

contact with modern jazz musicians and created relationships that were often very helpful to the growth of our art. Some of these relationships became

very personal and even sexual but not necessarily so. Often, they were supportive friendships which the musicians and their patrons enjoyed. Personally, I haven't received much help from white female benefactors. All the help

I needed, I got from my wife-an outspoken black woman, who will not let

me mess with the money-to whom I've been married since 1940. Regarding friendships across racial lines, because white males would sometimes lend

their personal support to our music, the bebop era, socially speaking, was a

major concrete effort of progressive-thinking black and white males and females to tear down and abolish the ignorance and racial barriers that were

stifling the growth of any true culture in modern America.

Number five: that beboppers used and abused drugs and alcohol is not

completely a lie either. They used to tell jokes about it. One bebopper walked

up to another and said, "Are you gonna flat your fifths tonight?" The other

one answered, "No, I'm going to drink mine." That's a typical joke about beboppers.

When I came to New York, in 1937, I didn't drink or smoke marijuana.

"You gonna be a square, muthafucka!" Charlie Shavers said and turned me

on to smoking pot. Now, certainly, we were not the only ones. Some of the

older musicians had been smoking reefers for forty and fifty years. Jazz musicians, the old ones and the young ones, almost all of them that I knew

smoked pot, but I wouldn't call that drug abuse.

The first guy I knew to "take off" was Steve, a trumpet player with Jimmie Lunceford, a young college kid who came to New York and got hung

up on dope. Everybody talked about him and said, "That guy's a dope addict! Stay away from him because he uses shit." Boy, to say that was really

stupid, because how else could you help that kinda guy?

Dope, heroin abuse, really got to be a major problem during the bebop

era, especially in the late forties, and a lotta guys died from it. Cats were always getting "busted" with drugs by the police, and they had a saying, "To

get the best band, go to KY." That meant the "best band" was in Lexington,

Kentucky, at the federal narcotics hospital. Why did it happen? The style of

life moved so fast, and cats were struggling to keep up. It was wartime, everybody was uptight. They probably wanted something to take their minds

off all the killing and dying and the cares of this world. The war in Vietnam

most likely excited the recent upsurge in heroin abuse, together with federal

narcotics control policies which, strangely, at certain points in history, en,-couraged narcotics abuse, especially among young blacks.

Everybody at one time or another smoked marijuana, and then coke became popular-I did that one too; but I never had any desire to use hard

drugs, a drug that would make you a slave. I always shied away from anything powerful enough to make me dependent, because realizing that everything here comes and goes, why be dependent on any one thing? I never

even tried hard drugs. One time on Fifty-second Street a guy gave me something I took for coke and it turned out to be horse. I snorted it and puked

160

/

The Forties

up in the street. If I had found him, he would have suffered bodily harm,

but I never saw him again.

With drugs like benzedrine, we played practical jokes. One record date

for Continental, with Rubberlegs Williams, a blues singer, I especially remember. Somebody had this date-Clyde Hart, I believe. He got Charlie

Parker, me, Oscar Pettiford, Don Byas, Trummy Young, and Specs Powell.

The music didn't work up quite right at first. Now, at that time, we used to,'

break open inhalers and put the stuff into coffee or Coca-Cola; it was a kick

then. During a break at this record date, Charlie dropped some into Rubberlegs's coffee. Rubberlegs didn't drink or smoke or anything. He couldn't

taste it. So we went on with the record date. Rubberlegs began moaning and

crying as he was singing. You should hear those records! But I wouldn't condone doing that now; Rubberlegs might've gotten sick or something. The

whole point is that, like most Americans, we were really ignorant about the

helpful or deleterious effects of drugs on human beings, and before we concluded anything about drugs or used them and got snagged. we should have

understood what we were doing. That holds true for the individual or the

society, I believe.

The drug scourge of the forties victimized black musicians first, before

hitting any other large segment of the black community. But if a cat had his

head together, nothing like that. requiring his own indulgence, could've

stopped him. I've always believed that. I knew several guys that were real

hip, musically, and hip about life who never got high. Getting high wasn't

one of the prerequisites for being hip, and to say it was would be inaccurate.

Number six is really a trick: that beboppers tended to express unpatriotic attitudes regarding segregation. economic injustice, and the American way

of life.

We never wished to be restricted to just an American context, for we

were creators in an a n form which grew from universal roots and which had

proved it possessed universal appeal. Damn right! We refused to accept racism,

poverty, or economic exploitation, nor would we live out uncreative humdrum lives merely for the sake of survival. But there was nothing unpatriotic

about it. If America wouldn't honor its Constitution and respect us as men,

we couldn't give a shit about the American way. And they made it damn near

un-American to appreciate our music.

Music drew Charlie Parker and me together, but Charlie Parker used to

read a lot too. As a great reader, he knew about everything, and we used to

discuss politics, philosophy, and life-style. I remember him mentioning Baudelaire-I think he died of syphilis-and Charlie used to talk about him all the

time. Charlie was very much interested in the social order, and we'd have

these long conversations about it, and music. We discussed local politics, too,

people like Vito Marcantonio, and what he'd tried to do for the little man in

New York. We liked Marcantonio's ideas because as musicians we weren't

paid well at all for what we created.

There were a bunch of musicians more socially minded, who were closely

connected with the Communist Party. Those guys stayed busy anywhere labor was concerned. I never got that involved politically. I would picket, if

:

i

"The Cult of Bebop" / 16 1

{'

necessary, and remember twice being on a picket line. I can't remember just

what it was I was picketing for, but they had me walking around with a sign.

Now, I would never cross a picket line.

Paul Robeson became the forerunner of Martin Luther King. I'll always

remember Paul Robeson as a politically-committed artist. A few enlightened

musicians recognized the importance of Paul Robeson, amongst them Teddy

Wilson, Frankie Newton, and Pete Seeger-all of them very outspoken politically. Pete Seeger is so warm; if you meet Pete Seeger, he just melts, he's

so warm. He's a great man.

In my religious faith-the Baha'i faith-the

Bab is the forerunner of

Raha'u'llah, the prophet. "Bab" means gate, and Paul Robeson was the "gate"

to Martin Luther King. The people in power made Paul Robeson a martyr,

but he didn't die immediately from his persecution. He became a martyr because if you are strangled for your principles, whether it's physical strangulation or mental strangulation or social strangulation, you suffer. The dues

that Paul Robeson paid were worse than the dues Martin Luther King paid.

Martin Luther only paid his life, quick, for his views, but Paul Robeson had

to suffer a very long time.

When the play Othello opened in New York with Paul Robeson, Jose Ferrer, and Uta Hagen, I went to the theater to see it. I was sitting way up in

the highest balcony. Paul Robeson's voice sounded like we were talking together in a room. That's how strong his voice was coming from the stage,

three miles away. Paul Robeson, big as he was, looked about as big as a

cigar from where I was sitting. But his voice was right up there next to me.

I dug Paul Robeson right away, from the first words. A lot of black people were against Paul Robeson; he was trying to help them and they were

talking against him, like he was a communist. I heard him speak on many

occasions and, man, talk about a speaker! He could really speak. And he was

fearless! You never hear people speak out like he did with everything arrayed against you and come out like he didr Man, I'll remember Paul Robeson until I die. He was something else.

Paul Robeson became "Mr. Incorruptibility." No one could get to him because that's the rarest quality in man, incorruptibility. Nothing supersedes that

because, man, there are so many ways to corrupt a personality. Paul Robeson stands as a hero of mine and he was truly the father of Malcolm X, another dynamic personality who I talked to a lot. Oh, I loved Malcolm, and

you couldn't corrupt Malcolm or Paul. We have a lot of leaders that money

corrupts, and power. You give them a little money and some power, and

they nut. They go nuts with it. Both Malcolm and Paul Robeson, you

couldn't get to them. The people in power tried all means at their disposal

to get them. So they killed Malcolm X and they destroyed Paul Robeson. But

they stood up all the time. Even dying, their heads were up.

One time, on the Rudy Vallee show, I should've acted more politically.

Rudy Vallee says, introducing me, "What's in the Ubangi department tonight?"'

2"Ubangi" is a general name for various groups of people who live in the Congo

Basin of Africa. Vallee (and others) used it as a demeaning reference to African

Americans.

A

162 / The Forties

I almost walked off the show. I wanted to sue him but figured there wasn't

any money in it, so I just forgot about it and we played. Musicians today

would never accept that, but then, somehow, the money and the chance to

be heard seemed more important.

We had other fighters, like Joe Louis, who was beautiful. I've known Joe

Louis since way, way back when I hung out in Sugar Ray's all the time, playing checkers. Sugar Ray's a good checker player, but dig Joe Louis. He'd

come down to hear me play. and people would want Joe Louis to have a

ringside seat. He'd be waaay over in a corner someplace, sitting there digging the music. If you announced him, "Ladies and gentlemen, the heavyweight champion of the world, Joe Louis, is sitting over there," he'd stand

up to take a bow and wave his hands one time. You look around again, he's

gone. Other guys I know would want a ringside seat, want you to announce

them and maybe come u p on the stage. But Joe Louis was like that. He was

always shy, beautiful dude. He had mother wit.

It's very good to know you're a part of something that has directly influenced your own cultural history. But where being black is concerned, it's

only what I represent, not me, myself. I pay very little attention to "Dizzy

Gillespie," but I'm happy to have made a contribution. To be a "hero" in the

black community, all you have to do is make the white folks look up to you

and recognize the fact that you've contributed something worthwhile. Laugh,

but it's the truth. Black people appreciate my playing in the same way I

looked up to Paul Robeson or to Joe Louis. When Joe would knock out someone, I'd say. "Hey . . . !" and feel like I'd scored a knockout. Just because

of his prowess in his field and because he's black like me.

Oh, there was a guy in Harlem, up there on the corner all the time

preaching. Boy, could he talk about white people! He'd get a little soap box.

I don't know his name, but everybody knew him. He wasn't dressed all fancy,

or nothing, and then he had a flag, an American flag. Ha! Ha! That's how I

became involved with the African movement, standing out there listening to

him. An African fellow named Kingsley Azumba Mbadiwe asked me who I

was and where I came from. I knew all the right answers. That was pretty

hip being from South Carolina and not having been in New York too long.

Out friendship grew from there; and I became attached to this African brother.

One time, after the Harlem riots, 1945, Mbadiwe told me, "Man, these white

people are funny here."

.'Whaddayou mean . . . ?"

"Well, they told me to stay outta Harlem," he said.

"Why is that?'' I asked.

"They say that it's dangerous for me u p here. I might get killed."

"What'd you tell them?"

"Well, I asked them how they gonna distinguish me from anybody else

up here? I look just like the rest of them."

Heh, heh, heh. It was at that time I observed that the white people

didn't like the "spooks" over here to get too close to the Africans. They didn't

want us-the

spooks over here-to

know anything about Africa. They

wanted you to just think you're somebody dangling out there, not like the

white Americans who can tell you they're German or French or Italian. They

"The Cult of Bebop" / 163

I

1

didn't want us to know w e have a line so that when you'd ask us, all w e

could say was w e were "colored." It's strange how the white people tried to

keep us separate from the Africans and from our heritage. That's why, today,

you don't hear in our music, as much as you d o in other parts of the world,

African heritage, because they took our drums away from us. If you go to

Brazil, to Bahia where there is a large black population, you find a lot of

African in their music; you g o to Cuba, you find they retained their heritage;

in the West Indies, you find a lot. In fact, I went to Kenya and heard those

cats play and I said, "You guys sound like you're playing calypso from the

West Indies."

A guy laughed and h e said to me, "Don't forget, w e were first!"

But over here, they took our drums away from us, for the simple reason

of self-protection when they found out those cats could communicate four

or five miles with the drums. They took our language away from us and

made us speak English. In slavery times, if they found out that two slaves

could speak the same African language, they sold off one. As far as our heritage goes, a few words creeped in like buckra-I used to hear my mother

say, "that ole poor buckran-buckra meant white. But with those few exceptions when they took our drums away, our music developed along a

monorhythmic line. It wasn't polyrhythmic like African music. I always knew

rhythm or I was interested in it, and it was this interest in rhythm that led

me to seize every opportunity to find out about these connections with Africa

and African music.

Charlie Parker and I played benefits for the African students in New York

and the African Academy of Arts and Research which was headed by Kingsley Azumba Mbadiwe. Eventually, Mbadiwe wound up becoming a minister

of state in Nigeria under one of those regimes, but over here, as head of the

African Academy, he arranged for us to play some benefit concerts at the

Diplomat Hotel which should've been recorded. Just me, Bird, and Max Roach,

with African drummers and Cuban drummers; no bass, nothing else. We also

played for a dancer they had, named Asadata Dafora.* (A-S-A-D-A-T-A

D-A-F-0-R-A-if you can say it, you can spell it.) Those concerts for the

African Academy of Arts and Research turned out to b e tremendous. Through

that experience, Charlie Parker and I found the connections between AfroCuban and African music and discovered the identity of our music with theirs.

Those concerts should definitely have been recorded, because w e had a ball,

discovering our identity.

Within the society, w e did the same thing we did with the music. First

w e learned the proper way and then w e improvised on that. It seemed the

natural thing to d o because the style or mode of life among black folks went

the same way as the direction of the music. Yes, sometimes the music comes

I'

'The first African dancer to present African dance in concert form in the United

States. Dafora is called "one of the pioneer exponents of African Negro dance and

culture." Born in Sierra Leone in 1890, Mr. Dafora studied and performed as a

singer at La Scala before coming in 1929 to the United States where he died in

1965. Dafora also staged the voodoo scene in the Orson Welles production of Macbeth.

164 / The Forties

first and the life-style reflects the music because music is some very strong

stuff, though life in itself is bigger. Artists are always in the vanguard of social change, but we didn't go out and make speeches or say "Let's play eight

bars of protest." We just played our music and let it go at that. The music

proclaimed our identity; it made every statement we truly wanted to make.

Number seven: that "beboppers" expressed a preference for religions other

than Christianity may be considered only a half-truth, because most black

musicians, including those from the bebop era, received their initial exposure

and influence in music through the black church. And it remained with them

throughout their lives. For social and religious reasons, a large number of

modern jazz musicians did begin to turn toward Islam during the forties, a

movement completely in line with the idea of freedom of religion.

Rudy Powell, from Edgar Hayes's band, became one of the first jazz musicians I knew to accept Islam; he became an Ahmidyah Muslim. Other musicians followed, it seemed to me, for social rather than religious reasons, if

you can separate the two.

"Man, if you join the Muslim faith, you ain't colored no more, you'll be

white," they'd say. "You get a new name and you don't have to be a nigger

no more." So everybody started joining because they considered it a big advantage not to be black during the time of segregation. I thought of joining,

but it occurred to me that a lot of them spooks were simply trying to be anything other than a spook at that time. They had no idea of black consciousness; all they were trying to do was escape the stigma of being "colored."

When these cats found out that Idrees Sulieman, who joined the Muslim faith

about that time, could go into these white restaurants and bring out sandwiches to the other guys because he wasn't colored-and he looked like the

inside of the chimney-they started enrolling in droves.

Musicians started having it printed on their police cards where it said

"race," "W" for white.3 Kenny Clarke had one and he showed it to me. He

said, "See, nigger, I ain't no spook; I'm white, 'W.' " He changed his name

to Arabic, Liaquat Ali Salaam. Another cat who had been my roommate at

Laurinburg, Oliver Mesheux, got involved in an altercation about race down

in Delaware. He went into this restaurant, and they said they didn't serve colored in there. So he said, "I don't blame you. But I don't have to go under

the rules of colored because my name is Mustafa Dalil."

Didn't ask him no more questions. "How do you do?" the guy said.

When I first applied for my police card, I knew what the guys were doing, but not being a Muslim, I wouldn't allow the police to type anything in

that spot under race. I wouldn't reply to the race question on the application black. When the cop started to type something in there, I asked him,

"What are you gonna put down there, C for me?"

'From 1940 to 1967, New York City required everyone who worked in a nightclub,

including jazz and other popular musicians, to be fingerprinted and to carry a special "cabaret card." Police could confiscate the cards for drug violations or other offenses, preventing musicians from working in the city. Ostensibly a means of combatting organized crime, the system reflected racism and class prejudice and

disrupted the careers of even major stars.

9

"The Cult of Bebop" i 165

"You're colored, ain't you?"

"Colored . . . ? No."

"Well, what are you, white?"

"No, don't put nothing on there," I said. 'yust give me the card." They

left it open. I wouldn't let them type me in W for white nor C for colored;

just made them leave it blank. WC is a toilet in Europe.

As time went on, I kept considering converting to Islam but mostly because of the social reasons. I didn't know very much about the religion, but

I could dig the idea that Muhammad was a prophet. I believed that, and there

were very few Christians who believed that Muhammad had the word of God

with him. The idea of polygamous marriage in Islam, I didn't care for too

much. In our society, a man can only take care of one woman. If he does a

good job of that, he'll be doing well. Polygamy had its place in the society

for which it was intended, as a social custom, but social orders change and

each age develops its own mores. Polygamy was acceptable during one part

of our development, but most women wouldn't accept that today. People

worry about all the women with no husbands. and I don't have any answer

for that. Whatever happens, the question should be resolved legitimately and

in the way necessary for the advancement of society.

The movement among jazz musicians toward Islam created quite a stir,

especially with the surge of the Zionist movement for creation and establishment of the State of Israel. A lot of friction arose between Jews and Muslims, which took the form of a semiboycott in New York of jazz musicians

with Muslim names. Maybe a Jewish guy, in a booking agency that Muslim

musicians worked from, would throw work another way instead of throwing

to the Muslim. Also, many of the agents couldn't pull the same tricks on Muslims that they pulled on the rest of us. The Muslims received knowledge

about themselves that we didn't have and that we had no access to; so therefore they tended to act differently toward the people running the entertainment business. Much of the entertainment business was run by Jews. Generally, the Muslims fared well in spite of that, because though we had some

who were Muslim in name only, others really had knowledge and were taking care of business.

Near the end of the forties, the newspapers really got worried about

whether I'd convert to Islam. In 1948 Lift. magazine published a big picture

story, supposedly about the music. They conned me into allowing them to

photograph me down on my knees, arms outstretched, supposedly bowing

to Mecca. It turned out to be a trick bag. It's of the few things in my whole

career I'm ashamed of, because I wasn't a Muslim. They tricked me into committing a sacrilege. The newspapers figured that if the "king of bebop" converted, thousands of beboppers would follow suit, and reporters questioned

me about whether I planned to quit and forsake Christianity. But that lesson

from Life taught me to leave them hanging. I told them that on my trips

through the South, the members of my band were denied the right of worshipping in churches of their own faith because colored folks couldn't pray

with white folks down there. "Don't say I'm forsaking Christianity," I said,

"because Christianity is forsaking me-or better, people who claim to be

Christian just ain't. It says in the Bible to love thy brother, but people don't

practice what the Bible preaches. In Islam, there is no color line. Everybody

is treated like equals."

With one reporter, since I didn't know much about the Muslim faith, I

called on our saxophonist, formerly named Bill Evans, who'd recently accepted Islam to give this reporter some accurate information.

"What's your new name?" I asked him.

"Yusef Abdul Lateef," he replied. Yusef Lateef told us how a Muslim mjssionary, Kahlil Ahmed Nasir, had converted many modern jazz musicians in

New York to Islam and how he read the Quran daily and strictly observed

the prayer and dietary regulations of the religion. I told the reporter that I'd

been studying the Quran myself, and although I hadn't converted yet, I knew

one couldn't drink alcohol or eat pork as a Muslim. Also I said I felt quite

intrigued by the beautiful sound of the word "Quran," and found it "out of

this world," "way out," as we used to say. The guy went back to his paper

and reported that Dizzy Gillespie and his "beboppers" were "way out" on the

subject of religion. He tried to ridicule me as being too strange, weird, and

exotic to merit serious attention.* Most of the Muslim guys who were sincere

in the beginning went o n believing and practicing the faith.

Number eight: that beboppers threatened to destroy pop, blues, and oldtime music like Dixieland jazz is almost totally false.

It's true, melodically, harmonically, and rhythmically, we found most pop

music too bland and mechanically unexciting to suit our tastes. But we

didn't attempt to destroy it-we simply built on top of it by substituting our

own melodies, harmonies, and rhythms over the pop music format and then

improvised on that. We always substituted; that's why no one could ever

charge us with stealing songs or collect any royalties for recording material

under copyright. We only utilized the pop song format as a take-off point for

improvisation, which to us was much more important. Eventually, pop music survived by slowly adopting the changes we made.

Beboppers couldn't destroy the blues without seriously injuring themselves. The modern jazz musicians always remained very close to the blues

musician. That was a characteristic of the bopper. He stayed in close contact

with his blues counterpart. I always had good friendships with T-Bone Walker,

B. B. King, Joe Turner, Cousin Joe, Muddy Waters-all those guys-because

we knew where our music came from. Ain't no need of denying your father.

That's a fool, and there were few fools in this movement. Technical differences existed between modern jazz and blues musicians. However, modern

jazz musicians would have to know the blues.

Another story is that we looked down on guys who couldn't read [music]. Errol1 Gamer couldn't read and we certainly didn't look down on him,

even though he never played our type of.music. A modem jazz musician

'Playing on this, sometimes in Europe I'd wear a turban. People would see me on

the streets and think of me as an Arab or a Hindu. They didn't know what to think,

really, because I'd pretend I didn't speak English and listen to them talk about me.

Sometimes Americans would think I was some kind of "Mohommedan" nobleman.

You wouldn't believe some of the things they'd say in ignorance. So to know me,

study me very closely; give me your attention and above all come to my concert.

"The Cult of Bebop" / 167

'

wouldn't necessarily have to read well to be able to create, but you couldn't

get a job unless you read music; you had to read music to get in a band.

The bopper knew the blues well. He knew Latin influence and had a

built-in sense of time, allowing him to set u p his phrases properly. He knew

chord changes, intervals, and how to get from one key to another smoothly.

He knew the music of Charlie Parker and had to b e a consummate musician.

In the current age of bebop, a musician would also have to know about the

techniques of rock music.

Ever since the days at Minton's w e had standards to measure expertise

in our music. Some guys couldn't satisfy them. Remember Demon, who used

to come to play down at Minton's; he came to play, but he never did, and

he would play with anybody, even Coleman Hawkins. Demon'd get u p on

the stand and play choruses that wouldn't say shit, but he'd b e there. We'd

get so tired of seeing this muthafucka. But he'd be there, and s o w e let him

play. Everybody had a chance to make a contribution to the music.

The squabble between the boppers and the "moldy figs," who played or

listened exclusively to Dixieland jazz, arose because the older musicians insisted o n attacking our music and putting it down. Ooooh, they were very

much against our music, because it required more than what they were doing. They'd say, "That music ain't shit, man!" They really did, but then you

noticed some of the older guys started playing our riffs, a few of them, like

Henry "Red" Allen. The others remained hostile to it.

Dave Tough was playing down at Eddie Condon's once, and I went down

there to see Dave because h e and his wife are good friends of mine. When

h e looked u p and saw me, h e says, "You the gamest muthafucka I ever seen

in my life."

"Whaddayou mean?" I said.

"Muthafucka, you liable to get lynched down in here!" he said. That was

funny. I laughed my ass off. Eddie Condon's and Nick's in the Village were

the strongholds of Dixieland jazz.

Louis Armstrong criticized us but not me personally, not for playing the

trumpet, never. He always said bad things 'about the guys who copied me,

but I never read where h e said that I wasn't a good trumpet player, that I

couldn't play my instrument. But when h e started talking about bebop, "Aww,

that's slop! No melody." Louis Armstrong couldn't hear what w e were doing.

Pops wasn't schooled enough musically to hear the changes and harmonics

w e played. Pops's beauty as a melodic player and a "blower" caused all of

us to play the way w e did, especially trumpet players, but his age wasn't

equipped to g o as far, musically, as w e did. Chronologically, I knew that

Louis Armstrong was our progenitor as King Oliver and Buddy Bolden had

been his progenitors. I knew how their styles developed and had been knowing it all the time; s o Louis's statements about bebop didn't bother me. I knew

that I came through Roy Eldridge, a follower of Louis Armstrong. I wouldn't

say anything. I wouldn't make any statements about the older guys' playing

because I respected them too much.

Time 1/28/47 quoted me: "Louis Armstrong was the one who popularized the trumpet more than anyone else-he sold the trumpet to the public.

He sold it, man.

168 / The Forties

"Nowadays in jazz we know more about chords, progressions-and we

try to work out different rhythms and things that they didn't think about when

Louis Armstrong blew. In his day all he did was play strictly from the soul,

just strictly from his heart he just played. He didn't think about no chordshe didn't know nothing about no chords. Now, what we in the younger generation take from Louis Armstrong . . . is the soul."

I criticized Louis for other things, such as his "plantation image." w e '

didn't appreciate that about Louis Armstrong, and if anybody asked me about

a certain public image of him, handkerchief over his head, grinning in the

face of white racism, I never hesitated to say I didn't like it. I didn't want the

white man to expect me to allow the same things Louis Armstrong did. Hell,

I had my own way of "Tomming." Every generation of blacks since slavery

has had to develop its own way of Tomming, of accommodating itself to a

basically unjust situation. Take the comedians from Step 'n Fetchit daysthere are new comedians now who don't want to be bothered with "Ah yassuh, boss. . . ." But that doesn't stop them from cracking a joke about how

badly they've been mistreated. Later on, I began to recognize what I had considered Pops's grinning in the face of racism as his absolute refusal to let

anything, even anger about racism, steal the joy from his life and erase his

fantastic smile. Coming from a younger generation, I misjudged him.

Entrenched artists, or the entrenched society, always attack anything that's

new coming in-in religion, in social upheavals, in any field. It has something to do with living and dying and the fear among the old of being replaced by the new. Louis Armstrong never played our music, but that

shouldn't have kept him from feeling or understanding it. Pops thought that

it was his duty to attack! The leader always attacks first; so as the leader of

the old school, Pops felt that it was his duty to attack us. At least he could

gain some publicity, even if he were overwhelmed musically.

"It's a buncha trash! They don't know what they're doing, them boys,

running off."

Mezz Mezzrow knocked us every time he'd say something to the newspapers over in Europe about bebop. "They'd never play two notes where a

hundred notes are due."

Later, when I went to Europe in 1948. they put a knife in my hand, and

Mezz Mezzrow was holding his head down like I was gonna chop it off. They

printed headlines: DIZZY IS GONNA CARVE MEZZ MEZZROW. . . . Thank goodness

this is the age of enlightenment, and we don't have to put down the new

anymore; that ferocious competition between the generations has passed.

In our personal lives, Pops and I were actually very good friends. He

came to my major concerts and made some nice statements about me in the

press. We should've made some albums together, I thought, just to have for

the people who came behind us, about twenty albums. It seemed like a good

idea some years later, but Pops was so captivated by Joe Glaser, his booking agent, he said, "Speak to Papa Joe." Of course that idea fizzled because

Joe Glaser, who also booked me at the time, didn't want anybody encroaching

o n Louis Armstrong. Pops really had no interest in learning any new music;

he was just satisfied to do his thing. And then Hello Dolly! came along and

7

"The Cult of Bebop" / 169

catapulted him into super, super fame. Wonder if that's gonna happen to me?

I wonder. Playing all these years, then all of a sudden get one number that

makes a big hero out of you. History repeating itself.

Number nine: that beboppers expressed disdain for "squares" is mostly

true.

A "square" and a "lame" were synonymous, and they accepted the complete life-style, including the music, dictated by the establishment. They rejected the concept of creative alternatives, and they were just the opposite

of "hip," which meant "in the know," "wise," or one with "knowledge" of life

and how to live.* Musically, a square would chew the cud. He'd spend his

money at the Roseland Ballroom to hear a dance band playing standards,

rather than extend his ear and spirit to take an odyssey in bebop at the Royal

Roost. Oblivious to the changes which replaced old, outmoded expressions

with newer, modern ones, squares said "hep" rather than "hip." They were

apathetic to, or actively opposed to, almost everything we stood for, like intelligence, sensitivity, creativity, change, wisdom, joy, courage, peace, togetherness, and integrity. To put them down in some small way for the sharpcornered shape of their boxed-in personalities, what better description than

"square"?

Also, in those days, there were supposedly hip guys who really were

squares, pseudohip cats. How do you distinguish between the pseudo and

the truly hip? Well, first, a really hip guy wouldn't have any racial prejudice,

one way or the other, because he would know the hip way to live is with

your brother. Every human being, unless he shows differently, is your brother.

Number ten: that beboppers put down as "commercial" people who were

trying to make money is 50 per cent a lie, only half true. We all wanted to

make money, preferably by playing modern jazz. We appreciated people who

tried to help us-and they were very few-because we needed all the help

we could get. Even during the heyday of bebop, none of us made much

money. Many people who pretended to help really were there for a rip-off.

New modern jazz nightclubs like the Royal Roost, which had yellow leather

seats and a milk bar for teenagers, and the Clique were opening every day,

all over the country. Bebop was featured on the Great White Way, Broadway, at both the Paramount and the Strand theaters. We received a lot of

publicity but very little money.

People with enough bucks and foresight to invest in bebop made some

money. I mean more than just a little bit. All the big money went to the guys

who owned the music, not to the guys who played it. The businessmen made

much more than the musicians, because without money to invest in producing their own music, and sometimes managing poorly what they earned, the

modern jazz musicians fell victim to the forces of the market. Somehow, the

jazz businessman always became the owner and got back more than his "fair"

share, usually at the player's expense. More was stolen from us during the

bebop era than in the entire history of jazz, u p to that point. They stole a

*"Hip cat" comes from Wolof, "hipicat"-a man who is aware or has his eyes open.

I

!

1

i

1

170 / The Forties

lot of our music, all kinds of stuff. You'd look up and see somebody else's

name o n your composition and say, "What'd he have to d o with it?" But you

couldn't d o much about it. Blatant commercialism we disliked because it debased the quality of our music. Our protests against being cheated and ripped

off never meant we stood against making money. The question of being politically inclined against commercialism or trying to take over anything never

figured too prominently with me. The people who stole couldn't create, so

I just kept interested in creating the music, mostly, and tried to make sure

my works were protected.

Number eleven: that beboppers acted weird and foolish is a damned lie.

They tell stories about people coming to my house at all hours of the day

and night, but they didn't d o it. They knew better than to ring my bell at

four o'clock in the morning. Monk and Charlie Parker came up there one

time and said, "I got something for you."

I say, "O.K., hand it to me through the door!" I've been married all my

life and wasn't free to d o all that. I could go to most of their houses, anytime, because they were always alone or had some broad. Lorraine never

stood for too much fooling. My wife would never allow me to d o that.

Beboppers were by n o means fools. For a generation of Americans and

young people around the world, who reached maturity during the 1940s, bebop symbolized a rebellion against the rigidities of the old order, an outcry

for change in almost every field, especially in music. The bopper wanted to

impress the world with a new stamp, the uniquely modern design of a new

generation coming of age.

Dizzy's Desiderata

Drawing o n lessons learned over the course of his career, Cillespie sketched this

guide t o achieving musical excellence in jazz. To Be, or Not . . . to Bop includes a

photograph of his handwritten notes.

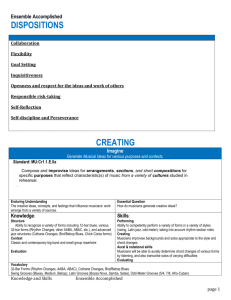

SOME OF THE PREREQUISITES FOR A

SUCCESSFUL JAZZ MUSICIAN

I. Mastery of the Instrument-important

because when you think of

something to play, you must say it quickly, because you don't have

time to figure h o w 4 w i t h l chords changing so quickly.

11. Style-which I think is the most difficult to master-inasmuch as there

are not too many truly distinctive styles in all of jazz.

111. Taste-is a process of elimination-some phrases that you play may

be technically correct but d o not portray the particular mood that you

are trying for.

W . Communication-after all, you make your profession jazz first, because you love it, and second, as a means of livelihood. So if there

is no direct communication with the audience for whom you are

playing-there goes your living.

'

"The Golden Age, Time Past" / 1 7 1

I'

V. Chord Progressions-as

there are rules that govern you biologically

and physically, there are rules that govern your taste musically. Therefore it is of prime interest and to one's advantage to learn the keyboard of the piano, as it is the basic instrument for Western music,

which jazz is an integral part of.

VI. Rhythm-which includes all of the other attributes, because you may

have all of these others and don't have the rhythmic sense to put

them together; that would negate all of your other accomplishments.

A SOMETIME JAZZMUSICIAN AND FREELANCE

photographer before he became a writer,

Ralph Ellison (1914-1 994) is best known for

his novel Invisible Man (1952) and for Shadow

and Act (1964), the collection of essays on literature, music, and cultural politics from

which this one is drawn. This essay is about

the 1940s, but it could not have been written then; as much as any selection in this volume, it directly addresses the problem of

99

"keeping time." Ellison's purpose is to conjure up vivid images of bebop's early days

even as he probes the faultiness of such recollections. With bebop, as with so many innovations, what seemed rebellious and risky

now seems historical and pioneering, even to

those who remember it firsthand. We have no way to think about the past apart

from the present in which it is being thought about, and since the present is complex and conflicted, so are our collective memories. Ellison discusses the varying reception of jazz in terms of clashing sensibilities, concluding with an insightful analysis of the jam session as the jazz musicians' academy, where traditions and

innovations meet in a delicate balance of individual competition with communal validation and interdependence.

32

"The Golden

Age, Time

Pasf

That which we do is what we are. That which we remember is, more ofien

than not, that which we would like to have been; or that which we hope to

be. Thus our memoy and our identity are ever at odds; our histoy ever a

tall tale told by inattentive idealists.

It has been a long time now, and not many remember how it was in the old

days; not really. Not even those who were there to see and hear as it happened, who were pressed in the crowds beneath the dim rosy lights of the

bar in the smoke-veiled room, and who shared, night after night, the mysterious spell created by the talk, the laughter, grease paint, powder, perfume,

sweat, alcohol and food-all blended and simmering, like a stew on the

Source: Ralph Ellison, "The Golden Age, Time Past," Esquire, January 1959; reprinted in

Shadow and Act (New York: Vintage Books, 19721, pp. 199-212.