Scott Canavan MUSC 151 2nd Analysis Paper Fall 2013 Parker and

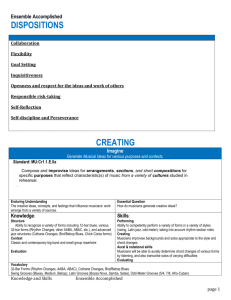

advertisement

Scott Canavan MUSC 151 2nd Analysis Paper Fall 2013 Parker and Gillespie as Revolutionaries Duke Ellington’s “Cottontail” and Charlie Parker’s “Shaw ‘Nuff” are both alternative interpretations of George Gershwin’s standard “I Got Rhythm.” In popular 32bar form, these arrangements follow the ‘rhythm changes’ as Gershwin laid out, a harmonic progression which artists could follow, thus enabling improvisatory musicians to collectively play head arrangements with their own melodies, and not risk infringing on any copyright laws. Although the song was originally written for a musical (Girl Crazy in 1930) it has been countlessly reinterpreted in context of a multitude of jazz genres, thus reflecting their respective qualities and aspects. In terms of reinterpretation and manipulation of stylistic traits, “Shaw ‘Nuff” is a radical breaking away from classical tradition. It demonstrates such an extreme reformation of finesse and technique, especially in the solos taken by Parker and Gillespie, that one must appreciate the exemplary forms of bebop to be manifestations of a strictly revolutionary spirit within themselves. Composed for big band during the swing era, “Cottontail” features an orchestral grouping of choirs and sectionals, segregated by brass horns and reeds, simultaneously playing alongside a three-piece rhythm section of drums, piano, and bass. Arranged for such a large band, Ellington was forced to compose this song featuring unorthodox choirs, interspersed with both horns and saxes; the melody is harmonized initially by both horns and saxes in unison (0:00-0:08) while later being contrapuntally interrupted by riffing, mostly done by the horns. (0:08-0:12) The tempo isn’t strikingly fast, but has a driving tempo instituted by both the walking bass and the ‘four to the floor’ pulse emitted by the drums. The solo Ben Webster takes at 0:29 is an attractive fluid melody, that slowly develops in note frequency and fluctuation between register as it begins to incorporate backing horn riffs. (0:44-0:53)(0:59-1:02) The little descending lines Webster articulates between 0:44-0:55 is pretty typical of this style of soloing: smooth warm lines, padded by space and tonal enunciation. Between 1:04-1:07 Webster repeats this pattern but rising up in crescendo to a heavy blasted note (1:08-9) followed by some vibrato. (1:12-1:13) As the horns enter again at 1:18, Webster’s solo lights up in intensity and depict some beautiful moving lines, with much more rapid oscillations and sliding between notes. (1:26-1:33)(More similar to Parker’s solo, as later mentioned) Another arranged section is intruded upon by a short sax solo (1:49-1:57), which leads into a brief piano interlude. (1:58-2:04) From then on (until 2:36) is a section functioning as development and contrasting material to the head, which is then capped by a recapitulation of the A section. (2:36) This is concluded by the head out at 3:01. Parker’s arrangement “Shaw Nuff” provides a stark contrast to “Cottontail,” as a quintet of piano, bass, drums, alto sax, and trumpet perform it. The intro is slightly unsettling as it is composed of just the drums and piano (an outstanding juxtaposition on its own) followed by the eighth notes played by the trumpet and sax in unison up till 0:17. Similarly to Ellington’s work, this piece is also a form of arranged music supported by a walking bass line. That’s essentially where the similarities end though. The rhythm section is incredibly unstable and features little foundation for the rest of the accompanying instruments. (as it is supposed to function) The drum kit basically just provides ride cymbal and rhythmic interjections on snare and bass, known as ‘dropping bombs.’ A concentrated stream of notes is dished out spasmodically by the piano (0:180:19) and section A follows with Gillespie and Parker playing the piece, as arranged, in homophony while the piano strikes a few supporting chords. (0:20-0:47) Parker’s solo follows and in just the first phrase, (0:43-0:54) playing an incredible amount of eighth notes at a ridiculously fast-paced tempo, his intonation and virtuosity shades over Webster’s own performance. The solo features many of the same repetitious scalar rise and falls as Websters own, (1:01-1:05) but he plays them with such expedient gracefulness that it’s almost impossible to separate all of the individual notes. Playing off a cycling of phrases and riffs in his head, (you can hear the repetition between 1:01-1:07) Parker’s solo is characteristic of bebop in its virtuosic complexity and the intricateness relayed through its breakneck tempo, only possibly executed by someone as practiced as Bird. Following Parker’s solo, Dizzy rips up a line pauses and then plunges into, plausibly, an even faster stream of notes, coincidentally with mountainous geography. The line he plays on a single breath (1:23-1:28) is incredible in its absurd concentration of notes, and virtuosic rhythmic discipline. The subsequent higher register half notes (1:28-1:30) bring in just enough feeling of space to be complimentary, but not in excess, before the next crazy plunging line (1:31-1:42). Listening to this stretch of music on its own personifies almost all of the radical aspects of Gillespie’s soloing style, especially the brightly blended notes he conveys between 1:34-1:38. The half-valving technique muddles the lower register notes and gives him the harmonic flavor to weigh against the up and down motion of the stream-lines. A piano solo follows, (1:42-2:08) reflecting on the qualities of the previous two soloists and adding its own passionate fervor. “Shaw Nuff” is best interpreted as a revolutionary break away from classical Jazz tradition (if it could be said they’re existed one after only prevailing for a little over 30 years) as it no longer catered to popular demand and appeal. Instead of being composed to be the next big radio swing hit, (such as Benny Goodman was attempting) bebop was music made by musicians purely for their own personal enjoyment and gratification. Bebop was so explicitly complex and technical that most white ‘imitation’ musicians couldn’t reproduce it and so it took on a uniquely African American tone. Like Jazz was originally intended, in Storyville or Dixieland, it was being preformed for all participants to enjoy without consideration of its reception or public appreciation; its aesthetic value was purely immediate and collective. While the style of Jazz was evolving in a certain sense, new styles had emerged that had not preexisted; Jazz was returning to its old roots form- that of a small combo: performing head sections and melodies and chiefly focusing on improvisatory skill and expertise. A revolutionary fervor was taking hold in the Jazz world as musicians began to become aware of their communal exploitation at the hands of the music industry and government indentures. Artists were sick of the production of jazz music for purely public consumption and were afflicted by the longing to have Jazz become more of a higher form of art. The virtuosity and technical skill that bebop required to play did just that. Bebop enabled musicians to produce contrafact arrangements, new melodic inventions over familiar harmonic progressions that allowed bebop musicians to get away without paying royalties, or composer wages. Thus they laid the grounds for a new musical genre to root itself and grow into a capacious flowering dimension, thus upending the accepted order of Jazz and instating something new.