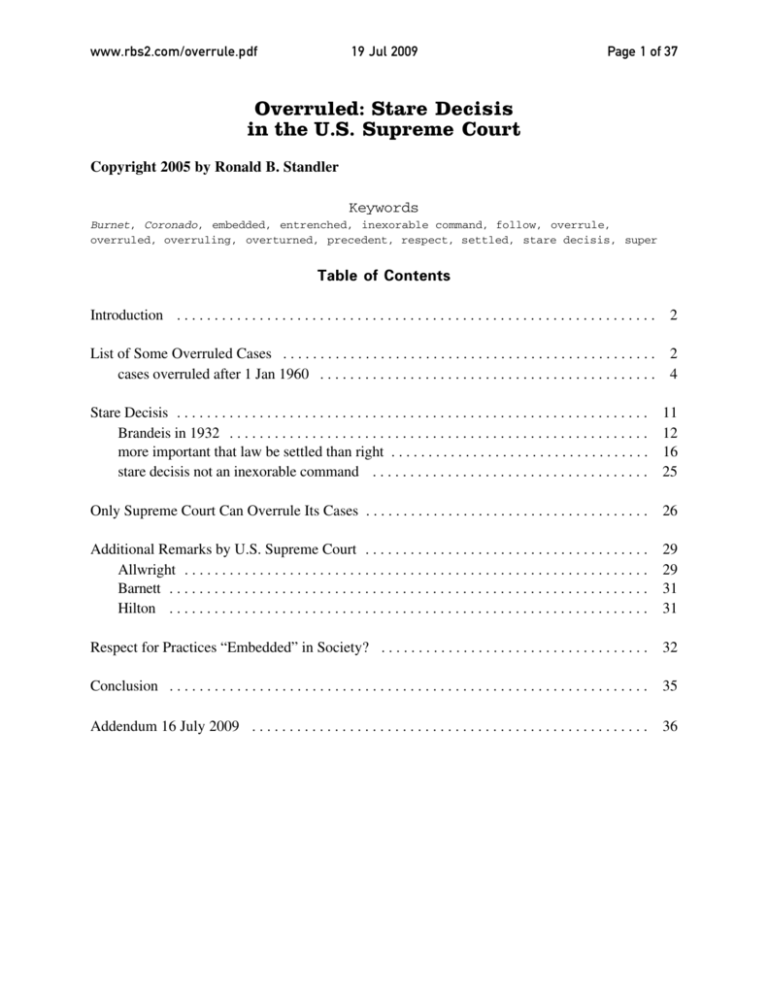

Overruled: Stare Decisis in the US Supreme Court

advertisement