BEST

OF

HIGHlIGHTS

fRoM

ReCenT ISSu

eS

HIGHlIGHTS

fR

ReC oM

e

n

T

I

S

S

u

e

S

Inside −

The Debt Ceiling Deal: The Case for Caving

Can Brian Moynihan Save Bank of America?

The God Clause and the Reinsurance Industry

Taco Bell and the Golden Age of Drive-Thru

The Big Business of Synthetic Highs

How Baidu Won China

Knut, the $140 Million Polar Bear

From Mao Jackets To Silk Suits

The Scent of Fast Money—and Tuna

August 8 — August 14, 2011

Bloomberg Businessweek

Opening Remarks

Compromise

HoLD oUT

Compromise

Deal no

one likes

Political

victory

HoLD oUT

Gop options

White house options

Political

victory

Financial

armageddon

The Case for Caving

Washington’s debt ceiling deal

satisfied no one. Game theory

explains why it couldn’t have

turned out any other way

By Brendan Greeley

Game theory does not concern itself

with good and evil. It seeks to predict

not which strategies are just, but which

are most effective. John von Neumann,

a Hungarian-born polymath with a sideline in predicting the blast radius of an

atomic bomb, co-authored the discipline’s seminal work, Theory of Games

and Economic Behavior, in 1944. He then

began thinking about war-game scenarios that weighed the likelihood of an exchange of nuclear weapons. “Early in nuclear negotiations,” says Steven J. Brams,

a New York University professor of poli-

2 | Bloomberg Businessweek’s Best of

tics who worked under former Defense

Secretary Robert McNamara during the

1960s, “we didn’t know that they were

not meant to be used. It took a few years

before strategists digested this.” At the

height of the Cold War, the application

of game theory convinced leaders of the

two nuclear-armed superpowers “that if

we’re thinking of using them, we’re in

deep s--t.”

This summer’s negotiations over

raising the debt ceiling seemed to present Democrats and Republicans with a

similar dilemma. Failure to reach a deal

threatened to bring on the economic

equivalent of a nuclear winter. The leaders of the two parties, Barack Obama

and Speaker of the House John Boehner (R-Ohio), appeared to grasp this, but

a vocal band of “Tea Party hobbits,” as

their fellow Republican, John McCain

of Arizona, dubbed them, refused to go

along. They made it clear they were not

only willing to bear the catastrophic consequences of a U.S. default, but that they

might actually welcome it. Trapped in a

classic game of “chicken”—a term game

theorists use, too—in which both players

entertain the option of killing everyone,

the President did what game theory suggests a rational actor would do. He recognized his potential maximum losses were

greater than his opponent’s. He caved.

Obama’s decision to agree to a deal

that calls for $2.1 trillion in spending cuts

over 10 years, with no increases in revenue, was greeted with scorn among his

own supporters and disdain from global

markets, which plunged at news of the

accord. Meanwhile, Tea Party Republicans

complained that the agreement didn’t go

far enough. The outcome of the debt ceiling talks left everyone in a foul mood, not

least the President himself, who signed

August 8 — August 14, 2011

Bloomberg Businessweek

the final legislation on Aug. 2 in the Oval

Office, alone and grim-faced.

And yet for all the collective self-loathing that attended the debt ceiling talks,

it’s important to remember that, like just

about everything in human behavior, it

was still reducible to a game. Looked at

through the prism of game theory, it’s

hard to see how the outcome could have

turned out any other way.

Biologists have adopted game theory

to describe successful adaptations. Labor

arbitrators have used it to ease negotiations. And Brams, who has many books

on game theory to his credit, has drawn

a decision tree for God’s last discussion

with Cain in which Cain can choose to

admit, deny, or defend his crime and

God, in turn, can choose to kill or punish

him. Looking back over the Summer of

Debt, Brams can’t find a single move by

any party that’s inconsistent with predictions from his discipline. Crucially, game

theory assumes that no one is crazy, and

it’s true in life that almost no one ever is.

There’s also a pragmatic reason to treat

your opponents as sane: You can’t make

predictions about their behavior unless

you do.

Almost everyone—even members of

the Tea Party—knows a hawk from a handsaw, and the best strategy is to assume

the other player has a rational goal and

try to figure out what it is. People act

crazy, but they’re at their craziest when

they want something. All you can do in

response is to make your most honest estimate of what the crazies actually want,

and respond as if they are methodically pursuing it. There is no advantage to

be gained, for example, in pointing out

that Kim Jong Il is a potbellied nut job in

a bad suit. Everything he’s done during

his reign as North Korea’s leader suggests

he’s an amoral, but sophisticated, negotiator. Unpredictability, says Brams, can

be a smart strategy.

Game theorists distinguish between

“cooperative” and “noncooperative”

games. A cooperative game looks to

divide a pie in a way that leaves both

sides with trust in the process. Binding

arbitration, where two sides are obliged

by law to submit to a judge’s decision, is

a cooperative game.

The two parties in Washington pretended to be playing a cooperative game

this summer. At one point, the President

and Boehner simultaneously urged the

other to get “serious” and behave like an

“adult.” The object of the game, as each

leader described it, was about how best

to divide the pain of closing the deficit, in

the same way a family sits down to a pile

of bills on the kitchen table.

The President’s bipartisan commission on deficit reduction, set up late last

year and chaired by Democrat Erskine

Bowles and Republican Alan Simpson,

also played a cooperative game. The rules

were clear and the game was closed, designed only for one iteration: a single

budget, to be sent to Congress if 14 of its

18 commission members approved it. The

commission produced the kind of document you’d expect from a well-designed

game, a series of compromises and innovations designed to distribute pain and

create trust in the result. But it failed, ultimately, because it couldn’t draw enough

votes to be turned into legislation. Six of

the seven who voted against it were sitting legislators. This is not a coincidence.

Washington, as a game theorist would describe it, is noncooperative.

A noncooperative game lacks a higher

authority to impose agreements on both

sides. In Washington, no politician is

bound to reach a compromise to solve

any long-term problem. Everyone, however, is playing a game called “election,”

and the only possible goal in that game is

to win the next one. If you hear someone

in Congress say, “Senator X is just playing

politics,” a perfectly legitimate response

is, “She has to. Those are the rules of the

Constitution.” If we grumble, as voters,

that we need to throw the bums out, all

we’re doing is subjecting a new set of

bums to the same game. Anyone who

promises to fix or change Washington is

merely attempting to impose a cooperative game on a town that, by design, can’t

play one.

Obama and the House Republicans,

says Steven Brams, were playing chicken this summer, a noncooperative, nonzero-sum game in which both players

can lose. A compromise outcome is difficult to achieve in chicken, because it’s

not stable. Brams says that each player

has an incentive to dissemble, because

There’s a pragmatic reason

to treat your opponents as

sane: You can’t predict their

behavior otherwise

he will achieve a better outcome for himself if he does.

A game theorist would say that the

President is trying to play a cooperative

game in a town that can’t play along with

him. The trouble for the White House is

that the Republicans aren’t playing a game

called “fix the budget deficit.” They’re necessarily playing one called “defeat Barack

Obama.” A reasonable offer seldom works

in a divorce; there’s no reason to expect it

would in Congress.

Obama and the Democrats should recognize that anger, too, is a tactic. Brams

argues that there’s no value in trying

to determine whether anger is real or

feigned; it has the same effect either

way. Anger comes of frustration, he says,

which in turn comes of a sense of powerlessness. But frustration can actually

turn a noncooperative game cooperative.

In the Aristophanes play Lysistrata, the

women of Athens and Sparta withhold

sex until their men sue for peace. Intermittent hostility among Greek city-states,

a noncooperative game, was bound into

the cooperative game of a negotiation,

brokered by thwarted lust.

The Tea Party, in this sense, has succeeded by adopting a rational frustration

strategy. Like the women in Lysistrata,

the Tea Partiers, in effect, have withheld

their affections from both the Democrats

and the Republican leadership. That has

forced Congress into what may prove to

be a cooperative game: the next round

of deficit negotiations, with a super

committee composed of members from

both parties charged with finding consensus —enforced by triggers that would

cause pain to both sides if they don’t.

You can find fault with the Tea Party’s

prescription for balancing the budget—

most economists do—but if they hadn’t

come to Washington last year, Congress

would have waited for a real bond crisis,

five or 10 years from now, to create its

super committee.

In a new book, Game Theory and the

Humanities, Brams offers another case

study in frustration strategy: Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth, who is desperate to see her husband crowned, but

fears he is too kind. And so she pours

her spirits into her husband’s ear, demanding that he murder King Duncan.

We will know, at the close of the next

round of negotiations, which game the

Tea Party has been playing: Balance the

Budget or Kill the King. <BW>

Businessweek.com | 3

o

To

ca’s slid

i

r

e

m

A

f

o

B ank

4 | Bloomberg Businessweek’s Best of

e into

emo

m

d

e

l

d

n

i

n has rek

w

o

n

k

n

u

the

o

ries

of

A

of

tion’s

a

n

e

h

t

n

a

C

ollapse.

c

’

s

r

e

h

t

o

r

f Lehman B

largest bank survive intact?

By Paul M

.B

arrett and

To

Dawn Kop

ec

ki

il

Businessweek.com | 5

the Countryw

On the afternoon of Aug. 23, Gary G. Lynch, the global chief of

62

legal, compliance, and regulatory relations for Bank of America, was attending a meeting in Washington when the floor

heaved. Although Lynch, a lanky 61-year-old attorney with

swept-back white hair, had never experienced an earthquake,

he possessed the good sense to get beneath a sturdy conference table, along with several other people. “If the ceiling

came down,” he recalls, “I thought we were dead.”

The ceiling held, despite the magnitude 5.8 quake rippling

from its epicenter in Virginia. Minutes later, Lynch pulled out

his BlackBerry and discovered another startling development:

a rumor rattling Wall Street that Bank of America might get

swept into an involuntary, government-orchestrated rescue

by its smaller rival JPMorgan Chase. “This is really getting

nuts,” he thought.

Lynch, who as the head of enforcement at the Securities and Exchange Commission in the late 1980s brought

Ivan Boesky and Michael Milken to heel, knew he’d come

under heavy fire when he parachuted into BofA this July. His

assignment: Defend against a seemingly endless barrage of

multibillion- dollar lawsuits and government investigations

concerning defective mortgage-backed bonds manufactured

at the height of the real estate bubble. No sooner did one

liability bomb explode than it was followed by another. Now

Lynch was doing duck-and-cover for real, while the bank’s

share price was pounded to within a whisker of $6, down

more than 50 percent since Jan. 1. The wild speculation about

a forced merger combined ominously with financial analyst

chatter that the mortgage onslaught would drain BofA’s capital, requiring it to sell more stock in desperation. Would Bank

of America, which just weeks earlier had reported a record

second-quarter loss of $8.8 billion, go the way of Bear Stearns

or Lehman Brothers?

It was starting to smell like 2008. Hotshot BofA investment

bankers gaped at $14 restricted stock units, granted in 2010 and

early 2011, which on paper had lost half of their value. They

began thumbing smartphones for contact info of potential alternative employers. Managers interrupted vacations to rush

into the office and calm valuable dealmakers.

Calm of a temporary sort returned two days later, thanks

to a theatrical Buffett-ex-machina intervention. Three years

ago, Bear was sold for scrap, while Lehman was allowed to

collapse into bankruptcy, setting off a global financial crisis

and recession. Announced on Aug. 25, Buffett’s purchase of

$5 billion in BofA preferred stock—on typical only-for-Warren

terms, including a $300 million annual dividend—allowed the

bank to edge back from the abyss, much as Buffett’s $5 billion

vote of confidence arrested a run on Goldman Sachs stock in

2008. On Sept. 6, only hours after he sat for an exclusive interview with Bloomberg Businessweek, BofA Chief Executive

Officer Brian T. Moynihan grabbed attention again by reshuffling his management ranks, elevating a pair of new co-chief

operating officers and ousting Sallie Krawcheck, the high-profile head of wealth management. After all the excitement, the

bank’s shares were up 19 percent from their nadir.

For now, Bank of America will not go the way of Lehman or

Bear. It has $400 billion in cash and liquid investments and,

more important, with $2.3 trillion in assets, it exemplifies

the sorry concept of “too big to fail.” No matter what anyone

says to the contrary, the U.S. government cannot afford to

6 | Bloomberg Businessweek’s Best of

there aren

’t

ide acquisitio

n,” says

allow a financial institution of that size to go down and drag

the rest of the country with it. BofA’s difficulties are too complex, however, to be solved by Buffett swashbuckling, executive replacements, or the retention of a really sharp lawyer.

America’s biggest bank is inextricably intertwined with a stilldebilitated U.S. housing market and an unemployment rate

stuck painfully above 9 percent.

“Bank of America is the purest reflection of the United

States economy of any of the largest financial institutions,” observes John A. Kanas, the chief executive officer of BankUnited.

BofA owns or services one in five home loans in the U.S., operates more than 5,700 retail branches, and serves 58 million

customers. “As America goes,” says Kanas, “so will Bank of

America.”

Then there’s Countrywide Financial, the worst corporate

acquisition in living memory. BofA’s former CEO, Kenneth D.

Lewis, bought the California subprime cesspool in 2008; its

stench has permeated the Charlotte-based bank ever since.

Rampant fretting over whether BofA has sufficient capital and

needs to sell more stock traces primarily to fear that it can’t

quantify its mounting write-offs and losses connected to hundreds of thousands of mortgages gone bad. So far, the aggregate Countrywide damage exceeds $30 billion.

“Obviously there aren’t many days when I wake up and think

positively about the Countrywide acquisition,” Moynihan said

on Aug. 10 during a conference call arranged to reassure anxious investors. Even some of his loyal aides concede that the

call, like a series of other pronouncements he has made this

year, didn’t comfort many uneasy money managers. Moynihan

received his CEO stars in a battlefield promotion in December

2009, after Lewis was perceived as losing investor confidence.

A compact 51-year-old former rugby player at Brown Univer-

BreNDaN HoFFmaN/BloomBerg

“Obvious

ly

September 12 — September 18, 2011

Bloomberg Businessweek

many day

s when I w

ake up an

d think p

ositively a

CEO Moyniha

n of the wors

bout

t merger in living m

emory.

The C o

untrywid

sity, he has admirers who praise his herculean work ethic and

intelligence. Charismatic he is not. Moynihan displays little if

any humor in public and swallows many of his words. His outof-earshot nickname within the bank, according to several employees, is “the Mumbler.” Asked for a self-evaluation during the

Aug. 10 conference call, he said: “I think my performance with

the management team in terms of transforming the company,

I think, has been strong. Our performance on the share performance has not been strong.”

More serious than his bouts of verbal artlessness, Moynihan

has overpromised on critical occasions, most notably in predicting prematurely that he would raise the bank’s penny-a-share

dividend this year. Such mistakes have obscured his reasonable

attempt to remake the bloated organization he inherited. To his

credit he is different from the generation of hubristic bankers

typified by Lewis, 64, and former Citigroup CEO Sanford I. Weill,

78. During a prolonged era of bipartisan antiregulatory ideolo�y, the Lewis-Weill cohort built the behemoths that were too

big to manage and ultimately too big for Washington to allow to

go under. The instability of those institutions contributed to the

panic of 2008 and its messy, unfinished cleanup.

Moynihan, who for six years toiled as Lewis’s lieutenant,

seems determined to learn from his former boss’s mistakes.

The younger man came into his job planning to sell off extraneous assets acquired by Lewis. In the process he has made the

bank a more focused institution that in the long run ought to

be less dangerous to the financial system. Whether he has the

dexterity to survive the current crisis and complete the task is

an open question.

In the space of only a dozen years, Bank of America transformed itself from an unremarkable regional business into a

financial supermarket of gargantuan proportions. Charlotte,

in turn, grew into the country’s second-biggest banking center

after New York.

Lewis, who never concealed his Southerner’s disdain for

hifalutin Wall Street types, capped an extraordinary acquisition spree in 2008, first by absorbing Countrywide, a subprime-mortgage factory on the verge of bankruptcy. Then,

with encouragement from the Bush Administration, he took

over Merrill Lynch, the faltering brokerage and investment

bank. Merrill turned out to be Lewis’s undoing; he lost his job

in 2009 when questions arose over whether he fully disclosed

its precarious financial condition as he pushed BofA shareholders to approve the $29 billion deal.

Moynihan had joined the ballooning BofA in 2004, when

Lewis paid $47 billion for FleetBoston Financial, itself the product of rapid-fire mergers and acquisitions. The Fleet executive

had a law degree from the University of Notre Dame but set his

sights higher than the legal department. Many of his Bostonbased former colleagues couldn’t—or chose not to—adjust to

life under the notoriously demanding Lewis. Moynihan adapted. Years later, in his 2005 book Winning, former General Electric Chief Executive Officer Jack Welch held him up as a model

of corporate stamina: “He showed exactly what you should

e damag

es? $30b

-plus

show if you want to survive a merger—enthusiasm, optimism,

and thoughtful support.”

At Bank of America, Moynihan didn’t specialize. Like a

leather-helmeted footballer of yore, he played offense and defense and, in a pinch, came in to punt. To make absolutely

sure he got no sleep, he often commuted to BofA’s large New

York outpost from Boston, where his family—wife, Susan Berry,

an attorney, and three young children—remained. His dedication inspires awe in the office. “Flash or pizzazz isn’t what clients want,” says Purna Saggurti, Bank of America’s chairman

of global corporate and investment banking. “Clients want content and a trusted adviser.”

As Lewis’s grip on his empire loosened in 2009, Moynihan, lacking deep roots in Charlotte or a proven CEO’s credential, was a dark horse candidate to succeed him. But the

bank’s directors were feuding, and other candidates fell away.

In December, Moynihan walked into a New York hotel room

to meet with the board of directors’ search committee. He

held a single sheet of paper on which he had written a strategic vision that actually could have fit on a note card: enough

already with the acquisitions, let’s get back to banking (or

words to that effect). He got the job.

Lewis hosted a large ceremony in Charlotte to introduce

the new CEO. “Many of you know him,” the outgoing chief

executive said of Moynihan, “because he’s been in so many

different jobs. And so, hopefully, he’ll be in this job much

longer than the last three or four.” The audience of Bank of

America employees, many wearing the company’s red-whiteand-blue flagscape lapel pin, laughed. Standing to the side

of the auditorium stage, Moynihan smiled tightly. The backhanded compliments continued. “Another unique characteristic about him,” Lewis noted, “is that he wanted the job.”

With that inauspicious endorsement, Moynihan took control

of a vast assemblage of businesses, which collectively had

received federal cash injections totaling $45 billion and appeared to be on life support.

Then, with miraculous speed, Merrill began to recover. The

acquisition that brought down Lewis became a surprise turnaround story. Federal bailout money was repaid. In April 2010,

to everyone’s relief, the rookie CEO announced a first-quarter

profit of $3.2 billion.

On a less happy note, Countrywide, a relative detail in

2008, was metastasizing into a disaster. When speaking privately, Bank of America executives will now acknowledge that

Countrywide behaved deplorably during the real estate frenzy.

In June 2010, BofA agreed to pay $108 million to settle federal

charges that Countrywide overcharged mortgage customers.

The firm “profited from making risky loans to homeowners

during the boom years, and then profited again when the loans

failed,” the Federal Trade Commission asserted. As a

➡

formal matter, BofA didn’t admit or deny the allegations,

63

Businessweek.com | 7

ear ll

Y

s

’

A

f

Bo From He

JAN

re

Shace

i

pr

FEB

to eddie

n

o

i

is and Fr

v

o

b pr nnie

MAR

da

e

t

c

je s e

e

r

d

rea

Fe

APR

ue

q

e

r

st

64

4

modifications a month by late 2010. Contrary to expectations,

though, home prices continued to slump in many areas, and

overall economic growth remained weak, despite the Federal

Reserve’s policy of keeping interest rates essentially at zero.

New threats came into focus. Even as state and federal

prosecutors revved up investigations of fraud in the issuing

and servicing of loans by Countrywide and its former competitors, other antagonists filed complaints. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the quasi-governmental housing finance companies,

argued that millions of mortgages they bought as part of their

mission to spur homeownership were turning out to be rotten.

Fannie and Freddie wanted Bank of America (and other lenders) to buy back billions in defective loans. In addition, there

were unhappy institutional investors that had purchased mortgage-backed securities, a type of bond assembled from bundles

of home loans. When broke borrowers stopped paying on the

mortgages, the bonds defaulted. Investors wanted compensation. On Oct. 18, 2010, one bondholder group led by BlackRock

and Pacific Investment Management (Pimco) sent BofA a stern

letter demanding the bank buy back mortgages packaged into

$47 billion of bonds. There was no reason to think the BlackRock demand would be the last of its kind.

A day later, BofA announced an $872 million third-quarter

2010 provision to resolve mortgage repurchase claims. That

compared with $1.25 billion in the second quarter and $526 million in the first. Moynihan tried to allay nervousness over a perpetually open spigot. “It’s a half billion, half billion, half billion,” he said during an investor conference call. “Those are

the kinds of numbers that would be more recurring.” In other

words: Half a billion dollars per quarter may seem like a lot to

ordinary folk, but we can handle it.

Not that Bank of America would surrender those half-abillions without a fight. “It’s day-to-day, hand-to-hand combat,”

Moynihan told an investor conference in New York in November 2010. All the same, he said in December, the bank planned

to increase its dividend as fast as possible—a signal that its capital levels were sound. “I don’t see anything that would stop

us,” he added. In January 2011, he had yet more encouraging

news: The bank would take an additional $3 billion provision

8 | Bloomberg Businessweek’s Best of

to settle claims from the government-sponsored enterprises

(GSEs) Fannie and Freddie. “We are pleased to put the GSEs

behind us this quarter,” Moynihan said on Jan. 21.

He spoke too soon. “Brian, while he is a very experienced executive, is an inexperienced chief executive,” notes

BankUnited CEO John Kanas, a Moynihan fan. “He has made a

couple of political mistakes, overpromising.”

On Mar. 23, Bank of America admitted in a regulatory filing

that the Federal Reserve had rejected its request for a dividend

increase in the second half of 2011. Among the four largest U.S.

lenders, a group rounded out by JPMorgan, Citigroup, and Wells

Fargo, BofA was the only one that didn’t announce a higher dividend after the Fed reviewed the companies’ financial health in

March. In an interview with Bloomberg News, Jonathan Hatcher,

a credit strategist at Jefferies in New York, called the Fed action

“a soft warning shot” across Bank of America’s bow.

More warnings followed. In April, BofA announced a $1.6 billion deal with Assured Guaranty to resolve claims tied to tainted mortgage-backed securities the insurance company had

covered. Outstanding mortgage-buyback demands climbed to

$13.6 billion, the bank said the same month. Then, in May, it

conceded in a regulatory filing that the cost of private-investor

demands might rise to between $11 billion and $14 billion, or

$4 billion more than the previously publicized range. Later

in May, Moynihan said that the settlement with Fannie Mae

might have sprung a leak, as the larger GSE stepped up its buyback demands. “We still have some work to do” on resolving

Fannie Mae demands, Moynihan conceded. In June, BofA said

it agreed to pay $8.5 billion to settle claims by the BlackRockPimco group of bondholders.

Bank of America generates an enormous amount of

revenue—$111.2 billion in 2010—so it can afford to settle a lot

of liability claims. “The problem,” says William B. Smith, the

CEO of Smith Asset Management, a New York hedge fund,

“is the unknown.” By midsummer it became apparent that

no one, including Bank of America, understood the ultimate

damage attributable to Countrywide.

Data: BloomBerg

olve

s

e

r

a

e d inc

l to ty

s $3 s by F

h

a

t

e

t

e

k

n

a

laim

b d uaran

A ta

s th divide

6

e

.

s

1

Bof solve c

o

G

l

for a

s a $ sured

re

e

Dis c

c

As

oun

Ann ms from

b

saying instead that it agreed to the settlement “to avoid the exing $13.6

clai

d

pense and distraction associated with litigating the case.”

n

tsta nds to

The expense and distraction were just beginning. In the

u

o

a

fall of 2010, with consumer complaints about mortgage abuses

se in e dem

a

e

increasing, BofA temporarily halted foreclosures across the

r

g

c

country. Moynihan said the bank was modifying Countryls in mortga

a

e

wide mortgage terms to keep people in their houses—20,000

Rev

.3

$13

MAY

JUN

JUL

AUG

4b

1

b

$11

stor

e

v

to

ttle ims

in

e

e

s

s

e

i

t

r

to co cla

t

va

i

b

h

r

p

5

g

i

s

8. k-Pim

e

that nds m

$

v

s

y

i

c

e

r

a

a

ced

o pBlackRo

h ar

t

c

dem

s

n

Con

e

e

y Ly

Agr

Gar

re

r

a

W

5

es $

s

a

k

h

urc d stoc

p

t

ffept referre

u

B

n

b in

er ll Street

g

r

me Wa

ed face on

c

r

fo

ur

Ru

of aChase s

s

r

mo ith

w

11

9/7/ 8

$7.4

Smith Asset Management, nevertheless, owns BofA stock.

“For those of us who are bullish, we don’t believe the mortgage hit is crippling,” William B. Smith says. “Those who are

bearish believe it is.” Like a number of other investors, he

takes solace from market analysis showing that BofA’s breakup value exceeds its current market value of about $76 billion.

“Tear this thing apart after you get down the road a bit,” says

Smith, and the stock could triple in value.

That’s not what Bank of America’s management or its

285,000 employees want to hear. Nor does the notion that

Bank of America might be worth more dismembered provide

any consolation to hundreds of thousands of homeowners

behind on their mortgage payments, some of whom accuse

BofA or its blacksheep subprime-mortgage unit of mistreating

them. “They were greedy. … It was a bad decision [to acquire

Countrywide],” says Don Barrett, a plaintiffs’ lawyer in Lexington, Miss., who is representing allegedly defrauded borrowers. “If Bank of America is going to survive, they’d better

get closure. They need closure with investors, but they also

need closure with the legitimate borrowers.”

Brian Moynihan’s private conference room on the 58th floor

of the Bank of America Corporate Center in downtown Charlotte has the usual photo of its occupant with the incumbent

President, along with other CEO knickknacks. Moynihan has

draped a canary-yellow T-shirt where every visitor can see it.

“Grind Together, Shine Together,” the black lettering on the

shirt instructs, and Moynihan presents himself as a grind-itout kind of guy.

M

es

ffl

u

sh eck

e

r

n

iha the d

oyn

He recognizes that he sees one company, while Wall Street

lately sees another. “We have the strongest capital we’ve ever

had in the company for decades,” he says. “We have the strongest liquidity.” He sounds frustrated. The bank has $115 billion

in what is known as Tier One common equity, which translates

to a capital ratio of 8.2 percent under today’s rules. That’s more

than enough to meet current requirements and puts BofA well

within shooting distance of tougher international standards

that will be phased in over coming years, Moynihan says. (“Litigation aside, there’s nothing wrong with this company,” says

Paul Miller, a former examiner for the Federal Reserve Bank

of Philadelphia who is now an analyst at FBR Capital Markets

in Arlington, Va.)

How will Moynihan close the perception gap?

“We have to keep educating and pounding and pounding and pounding,” he says. “The No. 1 thing for me was

to make the company clearer, more focused, get away from

the acquisition heritage of big is great, as opposed

➡

to great is great.”

Businessweek.com | 9

66

No question he’s slimmed the bank down. He has sold

off assets worth nearly $40 billion. These include stakes in a

bank in Brazil ($3.9 billion) and one in Mexico ($2.5 billion); a

$10.9 billion investment in BlackRock; a $2.3 billion portion

of an insurance company; more modestly valued credit-card

portfolios in the U.K., Spain, and Canada; and, most recently,

half of Bank of America’s stake in China Construction Bank,

which sold for $8.3 billion. The Lewis-era binge left BofA with

all kinds of pointless overhead. “Nobody sat down and said,

‘We want 63 data centers.’ We inherited 63 data centers,” says

Moynihan. He intends to get that down to the single digits.

He frames the Sept. 6 management shake-up as a streamlining maneuver. Where there had been no chief operating

officer, now there will be two, promoted from within: David

C. Darnell will oversee businesses responsible for serving

individual customers, including deposits, credit cards, home

mortgages, and wealth management. Thomas K. Montag will

supervise operations related to corporations and institutional

investors. “They are accountable now for delivering our entire

franchise to all our customers and clients,” Moynihan said in a

written announcement. Joe Price, who had been president of

consumer and small business banking, was ousted along with

Sallie Krawcheck, the former wealth-management chief.

Moynihan is in no mood, however, to apologize. He says he

has no regrets about promising to raise the dividend and then

not being able to follow through. He waves off the criticism as

missing the larger point that shareholders will benefit in the

long run from a stronger, better capitalized bank. Similarly, he

dismisses suggestions that he’s an ineffective public communicator. His job is to make sure that every employee understands

that at all times they should be serving one of the bank’s three

customer groups: individuals, companies, and institutional investors. Because he has pounded this home so consistently, he

adds, “There’s 285,000 people could probably give that speech

right now.” (Or maybe fewer. Moynihan has announced 6,000

layoffs so far this year, with more to come.)

The CEO doesn’t utter the word “Countrywide” voluntarily.

He won’t comment on one option—putting the unit into bankruptcy—and he refers to the mess in shorthand: “We have to

keep taking uncertain risks and eliminate them, and that’s

what we’ve been doing in the mortgage area.” For Countrywide details, he recommends talking to Gary Lynch.

Bank of America’s top in-house lawyer works in a serene

sanctum high above Sixth Avenue in New York. The room features cool white marble and white leather. Lynch has made

a career of remaining unruffled—at the SEC during its 1980s

insider-trading investigations, later as a partner at the New

York corporate law firm Davis Polk & Wardwell, and then as

the senior-most attorney at investment banks Credit Suisse

First Boston and Morgan Stanley.

It’s no wonder that Moynihan hired Lynch, but is the attorney still glad he moved over to Bank of America? Lynch laughs, a

public relations man holds his breath, and the lawyer says yes.

With professorial precision he proceeds to sort the categories of legal risks facing BofA into three “buckets.” Over

time, he explains, the bank can gradually empty each bucket.

First, there are “representations and warranties” claims, such

as those made by the GSEs and the BlackRock-Pimco bondholder group. Those parties want BofA to buy back mortgages

allegedly based on false information about borrowers or property. Bank of America has negotiated compromise payments

for most of the reps-and-warranties claims.

Bucket No. 2 contains fraud lawsuits filed by investors who

bought mortgage-backed securities, which have lost value. A

lawsuit filed Aug. 8 by American International Group, the New

York-based insurance giant, sits in that bucket; AIG seeks damages of $10 billion. Lynch says the bank will fight the vast majority of such suits. “I’d much rather be sued by AIG than by

someone who has never purported to be an expert on mortgages and risk management,” he notes. His point is that AIG is

a sophisticated financial player that should have known that

subprime-backed bonds could explode.

Finally, there’s a bucket for government allegations that

Countrywide generated fraudulent foreclosure documents.

BofA and other large lenders are skirmishing with the 50 state

attorneys general in hopes of reaching a mass settlement whose

collective price tag has been estimated at $20 billion.

Sweeping a long arm over his imaginary litigation receptacles, Lynch seems sure of himself. Statutes of limitation are

running out, and that’s why so many lawyers rushed to the

courthouse this summer, he says. “We’re comfortable that

these securitization cases will go away or be settled for cents

on the dollar,” he adds. “At the end of the day, do we

➡

have ample capital to get through this? Absolutely.”

ry Lynch

Legal ace Ga

’s risks

divides BofA

ckets

into three bu

,” says Lynch

olutely

s

b

A

?

is

th

h

g

u

ro

capital to get th

le

p

m

a

e

v

a

h

e

“Do w

$8.5b

$10b

$20b

Loan Origination

In 2008, Bofa bought subprime home

lender Countrywide Financial, a firm whose

lax underwriting led to soaring defaults on

mortgages and “putback” claims from those

who bought or insured them. In one proposed

settlement, the bank would pay private

investors $8.5 billion.

Mortgage-Backed Securities

Bank of america is accused by the insurer

american International group and other

investors of bundling shoddy loans into

securities while grossly understating the

assets’ risks. aIg alone is seeking to recoup

more than $10 billion from the lender. Bofa

denies the charges.

Mortgage Servicing

Bank of america and other mortgage

servicers are accused by state and

federal investigators of employing

“robosigners” to submit improper

foreclosure documents; a settlement

could cost the five biggest firms

$20 billion.

10 | Bloomberg Businessweek’s Best of

BUCKet: DaNNY SmYtHe/alamY; lYNCH: rICK maImaN/BloomBerg

September 12 — September 18, 2011

Bloomberg Businessweek

September 12 — September 18, 2011

Bloomberg Businessweek

September 12 — September 18, 2011

Bloomberg Businessweek

many day

h n I wake

“For thossew

of ue

s who are buu

pllais

ndht,h

wien

dk

onp

’t bo

elie

vteith

CEO Moyniha

em

s

ortgage hit is crip

i

ve

l

n of thsays

y

pling,”

about

e winves

orstor

t mBill

“Tho

se

who

erSmit

are

bear

ish

gerh.

belie

ve

it

is.

The Co in living memory. triple

untvalue

stock could

rywof

Tear this thing apart,” and the

idthe

ed

68

sity, he has admirers who praise his herculean work ethic and

intelligence. Charismatic he is not. Moynihan displays little if

someone

is going

say, ‘O.K.,

Counselor,

tell meHis

exactly

any “If

humor

in public

andtoswallows

many

of his words.

outwhat you’re

going towithin

pay out,’

I can’taccording

do that, and

I wouldn’t

of-earshot

nickname

the bank,

to several

emtry,” Lynch

acknowledges.

What’s

he says, theduring

mortgage

ployees,

is “the

Mumbler.” Asked

formore,

a self-evaluation

the

litigation

won’t getcall,

resolved

in three

months

or six months

or

Aug.

10 conference

he said:

“I think

my performance

with

a year.

“Past cases

of this

type have

been working

the

the

management

team

in terms

of transforming

thethrough

company,

forbeen

years.”

Iprocess

think, has

strong. Our performance on the share perforThehas

problem,

his clients’ perspective, is that even

mance

not beenfrom

strong.”

when

Bank

of America

says itofhas

something

resolved,

new

More

serious

than his bouts

verbal

artlessness,

Moynihan

doubts

clutter the

The state AGs’

seems,

has

overpromised

onbucket.

critical occasions,

most settlement

notably in predictin broad

outline,that

likehe

a reasonable

Big lenders

fork

over

ing

prematurely

would raiseidea.

the bank’s

pennya-share

cash to make

borrowers

whole

andobscured

modify his

thereasonable

terms on

dividend

this year.

Such mistakes

have

some mortgages

keep theirhe

homes.

But To

lately,

attempt

to remakeso

thepeople

bloatedcan

organization

inherited.

his

attorneys

Newthe

York,

Delaware,

and Nevada

have

credit

he isgeneral

differentinfrom

generation

of hubristic

bankers

broken

ranks,

saying

theyformer

don’t want

to rush

toSanford

a truce because

typifi

ed by

Lewis,

64, and

Citigroup

CEO

I. Weill,

they’re

notathrough

investigating

lenders’

misbehavior. ideolMore78.

During

prolonged

era of bipartisan

antiregulatory

over,the

the

New Yorkcohort

prosecutor,

Eric

T. Schneithat

derman,

has

o�y,

Lewis-Weill

built the

behemoths

were too

challenged

the

propriety

oftoo

thebig

$8.5

settlement

with

big

to manage

and

ultimately

forbillion

Washington

to allow

to

private

uncertainty

that pact,to

too.

go

under.bondholders,

The instabilitycasting

of those

institutionson

contributed

the

panic of 2008 and its messy, unfinished cleanup.

ForMoynihan,

all the angst

Bank

of America

on Wall lieutenant,

Street and

whoover

for six

years

toiled as Lewis’s

in the determined

media, regulators

at the

Federal

Reserve

andmistakes.

Treasury

seems

to learn

from

his former

boss’s

Dept.,

speaking

because

are not

to

The

younger

manprivately

came into

his jobthey

planning

to authorized

sell off extracomment

onacquired

particular

saythe

they

have he

watched

Moynineous

assets

by banks,

Lewis. In

process

has made

the

han’saperformance

are mostly

by what

they’ve

bank

more focusedand

institution

that pleased

in the long

run ought

to

seen.

fact they applaud

his shrinking

the

company

be

lessIn

dangerous

to the financial

system.

Whether

heand

has simthe

ilar moves

some the

of his

competitors.

dexterity

toby

survive

current

crisis and complete the task is

One of

the paradoxes of the 2008 crisis has been that, in

an open

question.

its aftermath, a U.S. financial industry overpopulated with

institutions

too big

to failBank

became

even more

conIn

the spaceconsidered

of only a dozen

years,

of America

transsolidated.

Mergers

such

as Bank of America’s

acquisition

formed

itself

from an

unremarkable

regional business

into of

a

Countrywide,

and JPMorgan’s

absorption

of Bear

fiMerrill

nancialand

supermarket

of gargantuan

proportions.

Charlotte,

Stearns

and into

Washington

Mutual

have produced

a quartet

of

in

turn, grew

the country’s

second-biggest

banking

center

megabanks

that together hold $7.7 trillion in assets, or 56.8 perafter

New York.

cent

of thewho

U.S.never

total, concealed

compared with

45.2 percentdisdain

of the total

Lewis,

his Southerner’s

for

before the

crisis.

hifalutin

Wall

Street types, capped an extraordinary acquiEven

with

added

the potential

risk

sition

spree

inthis

2008,

firstconsolidation,

by absorbing and

Countrywide,

a subit perpetuates in factory

the event

a true

investor

or depositor

run

prime-mortgage

onofthe

verge

of bankruptcy.

Then,

on any

of the megabanks,

regulators

say there has not

been

with

encouragement

from the

Bush Administration,

he took

muchMerrill

for them

to do

about

Bank ofbrokerage

America’sand

difficulties.

New

over

Lynch

, the

faltering

investment

oversight

tools

created

financial

reform

legbank.

Merrill

turned

outbytothe

beDodd-Frank

Lewis’s undoing;

he lost

his job

islation

enacted

in 2010arose

are still

crafted.

Anddisclosed

industry

in

2009 when

questions

overbeing

whether

he fully

lobbyists

are fistill

trying

to bluntasrules

on how

much

capital

its

precarious

nancial

condition

he pushed

BofA

shareholdbanks

must hold,

howbillion

they sell

mortgages, and what kind of

ers

to approve

the $29

deal.

trading

they can

for their

accounts.

To avoid

future

taxMoynihan

haddojoined

theown

ballooning

BofA

in 2004,

when

payerpaid

bailouts,

the law

major

banks toitself

submit

Lewis

$47 billion

forrequired

FleetBoston

Financial,

the“living

prodwills,”

or plans

how they

be efficiently

dismembered

uct

of rapid-fi

re for

mergers

and could

acquisitions.

The Fleet

executive

in dire

circumstances.

ButUniversity

details on of

theNotre

living-will

are

had

a law

degree from the

Dameprocess

but set his

still being

debated;

nolegal

willsdepartment.

have been submitted

to Washingsights

higher

than the

Many of his

Bostonton. (Regulators

say Bank

of Americachose

hasn’t

gotten

into livbased

former colleagues

couldn’t—or

not

to—adjust

to

ing-will

territory,

becausedemanding

the bank has

cashMoynihan

on hand and

the

life

under

the notoriously

Lewis.

adaptability

tolater,

borrow

more.)

far the

Dodd-Frank

perverse

ed.

Years

in his

2005So

book

Winning,

formerlaw’s

General

Eleceffect

hasExecutive

been to heighten

uncertainty

without

disentangling

tric

Chief

Officer Jack

Welch held

him up

as a model

thecorporate

combinations

of investment

banking

with

consumer

and

of

stamina:

“He showed

exactly

what

you should

amages?

$30b-pl

us

commercial banking that proved so perilous in the wake of the

housing bubble.

One

positive

is that

there are more cops walking

the

show

if you

wantchange

to survive

a merger—enthusiasm,

optimism,

banking

beat. About

30 examiners from the Fed’s Richmond

and

thoughtful

support.”

(Va.)

areAmerica,

assigned Moynihan

full-time to monitoring

Bank ofLike

AmerAt branch

Bank of

didn’t specialize.

a

ica, up from 14 in footballer

2007. Fed of

staff

members

say off

they

areand

able

to

leather-helmeted

yore,

he played

ense

degive closer

to the

bank’s

securities

and

loanabsolutely

portfolios,

fense

and, scrutiny

in a pinch,

came

in to

punt. To

make

as well

associated

its assets

thelarge

adequacy

sure

he as

gotthe

norisk

sleep,

he oftenwith

commuted

toand

BofA’s

New

of itsoutpost

capital.from

In early

summer,

when

Fed officials requested

opYork

Boston,

where

his family—wife,

Susan Berry,

tions

BofA might

consider

if overall

economic conditions

serian

attorney,

and three

young

children—remained.

His dedicaously

eroded,

theinbank

responded

that

one possibility

would

tion

inspires

awe

the offi

ce. “Flash

or pizzazz

isn’t what

clibe towant,”

issue asays

separate

of shares

linked

to the performance

ents

Purnaclass

Saggurti,

Bank

of America’s

chairman

ofglobal

Merrillcorporate

Lynch, according

to BofA.

Moynihan

doeswant

not think

of

and investment

banking.

“Clients

consuchand

a step

will be

needed and similarly has no plans to sell

tent

a trusted

adviser.”

more

BofA common

his aides

say.

As Lewis’s

grip onstock,

his empire

loosened

in 2009, MoyniFeddeep

examiners

supposed

be keeping

ancreeye

han,While

lacking

roots inare

Charlotte

or to

a proven

CEO’s

out for reckless

practices

within BofA,

there’s ahim.

danger

dential,

was a dark

horse candidate

to succeed

But that

the

other government

officials

andand

politicians

could hasten

fresh

bank’s

directors were

feuding,

other candidates

fellaaway.

financial

meltdown

as they

seekinto

their

pound

of hotel

assetsroom

from

In

December,

Moynihan

walked

a New

York

Bank

of with

America.

The state-AG

foreclosure

has identito

meet

the board

of directors’

searchprobe

committee.

He

fied troubling

pastofpractices,

thehe

handful

of prosecutors

held

a single sheet

paper onbut

which

had written

a strateholding

a resolution

could have

jeopardize

prize

theyenough

desire.

gic

visionup

that

actually could

fit on athe

note

card:

Likewise,

Fannie

Mae and Freddie

two to

of banking

BofA’s other

already

with

the acquisitions,

let’s Mac,

get back

(or

main antagonists,

areHe

each

words

to that effect).

gotalmost

the job.80 percent-owned by U.S.

taxpayers

as a result

of rescues

at the

depths ofto

the

financial

Lewis hosted

a large

ceremony

in Charlotte

introduce

crisis.

The

GSEs

are “we

if they

take Bank

of

the

new

CEO.

“Many

of the

youpeople”;

know him,”

thehelp

outgoing

chief

America down,

will“because

have to mop

Onin

Sept.

2, the

executive

said oftaxpayers

Moynihan,

he’sup.

been

so many

Federal

Finance

Agency, the

Washington

of

diff

erentHousing

jobs. And

so, hopefully,

he’ll

be in thisregulator

job much

Fanniethan

and the

Freddie,

joined

fray.

In its

own brace

of lawlonger

last three

orthe

four.”

The

audience

of Bank

of

suits, theemployees,

FHFA accused

Bank

of America

and 16 other

lenders

America

many

wearing

the company’s

red-whiteof misleading

Fannie

andpin,

Freddie

aboutStanding

billions of

of

and-blue

flagscape

lapel

laughed.

todollars

the side

mortgagebacked securities.

of

the auditorium

stage, Moynihan smiled tightly. The backThe problem

for Moynihan,

says

Lou Barnes,

“ischaracterthat everyhanded

compliments

continued.

“Another

unique

one is

suinghim,”

him, Lewis

he can’t

know“is

when

will the

stop,job.”

and

istic

about

noted,

thatthe

hesuits

wanted

meanwhile—hello?—the

economy isn’tMoynihan

bouncing back,

and it’s

With

that inauspicious endorsement,

took control

damned

to get aof

home

loan approved

here.” Barnes,

of

a vast tough

assemblage

businesses,

whichout

collectively

had

a banker federal

and credit

analyst

at Premier

Mortgage

Groupand

in Boulreceived

cash

injections

totaling

$45 billion

apder, Colo.,

argues

that

Moynihan “looks to be doing as well as

peared

to be

on life

support.

anyThen,

little with

Dutch

boy can—sticking

his fingers

into

the

dike.” The

miraculous

speed, Merrill

began

recover.

But more

cracks

keep

opening

Barnes

ticks off

the

acquisition

that

brought

down

Lewis up.

became

a surprise

turnlatest statistics

frombailout

Lender

Processing

Services,

a major

around

story. Federal

money

was repaid.

In April

2010,

home-loan

4.1rookie

million

loans

nationwide

are 90 or

to

everyone’sservicer:

relief, the

CEO

announced

a first-quarter

moret of

days

delinquent

profi

$3.2

billion. or in foreclosure; delinquency rates are

twice

norm;

foreclosure rates

are eight

times

On their

a lesshistorical

happy note,

Countrywide,

a relative

detail

in

higherwas

than

the historicalinto

average;

moreWhen

than 40

percent

of

2008,

metastasizing

a disaster.

speaking

pri90-days-plus

loans have

made

a payment

in

vately,

Bank ofdelinquent

America executives

willnot

now

acknowledge

that

more than a behaved

year.

Countrywide

deplorably during the real estate frenzy.

BofA2010,

is more

exposed

scary

figurestothan

any

other

In June

BofA

agreedto

tothose

pay $108

million

settle

federal

bank. Moynihan

“has got toovercharged

know there are

more losses

ahead,

charges

that Countrywide

mortgage

customers.

enough

kill ated

bank,”

says

Barnes.

“Noloans

model

for what

The

firmto“profi

from

making

risky

to exists

homeowners

——With

reporting

by Max

Cristina

happens

during

thenext.”

boom<BW>

years,

and then

profited

againAbelson,

when the

loans

Alesci, Roben

Farzad,Trade

Cheyenne

Hopkins, Robert

Schmidt,

failed,”

the Federal

Commission

asserted.

As a Hugh

➡

Son, Craig

Torres,

and

Karen

Weise

formal

matter,

BofA

didn’t

admit

or deny the allegations,

63

Businessweek.com | 11

the riSk buSineSS CAn tell

uS A lot About CAtAStropheS.

why don’t we liSten?

the god

12 | Bloomberg Businessweek’s Best of

ClAuSe

by brendAn greeley

Businessweek.com | 13

September 5 — September 11, 2011

Bloomberg Businessweek

60

At 9:03 A.m. on September 11, 2001,

britt newhouSe Stood in the lobby on

the 52nd floor of the South tower of the

world trAde Center. After united AirlineS

flight 175 bAnked Above the hArbor behind

him, it wAS pointed At the 50th floor. if

not trimmed CorreCtly, An AirplAne will

riSe AS it ACCelerAteS, And the mAn who hAd

killed And replACed the AirplAne’S pilot

Added power until he hit the South

tower 24 floorS Above newhouSe. he

doeSn't remember the Sound of the impACt.

At the time, Newhouse ran Guy Carpenter’s Americas operation. Guy Carpenter brokers reinsurance treaties, which

protect insurers when a catastrophe—a hurricane or an

earthquake—causes losses on a large number of policies. Reinsurance, in essence, is insurance for insurers.

Consumers don’t tend to know what reinsurance is because it never touches them directly. Reinsurers, massively capitalized and often named after the places where they

were founded—Cologne Re, Hannover Re, Munich Re, Swiss

Re—make their living thinking about the things that almost

never happen and are devastating when they do. But even

reinsurers can be surprised. And the insurers who make up

their market put them on the hook for everything, for all the

risks that stretch the limits of imagination. This is what the

industry casually refers to as the “God clause”: Reinsurers are

14 | Bloomberg Businessweek’s Best of

ultimately responsible for every new thing that God can come

up with. As losses grew this decade, year by year, reinsurers

have been working to figure out what they can do to make the

God clause smaller, to reduce their exposure. They have billions of dollars at stake. They are very good at thinking about

the world to come.

Lloyd’s, the London-based company that invented the

modern profession of insurance, publishes a yearly list of

what it calls “Realistic Disaster Scenarios.” The list imagines

such events as two consecutive Atlantic seaboard windstorms

or an earthquake at the New Madrid fault in the Mississippi

Valley, either of which could strain or break an insurer’s balance sheet. By 2001, Lloyd’s had already envisioned two airliners colliding over a city, launching claims on hull insurance

for the planes, property insurance and workman’s comp on

oPEnIng SPrEAd: doug KAntEr/AFP/gEtty ImAgES; tHIS PAgE: lAmbErt/ArcHIVE PHotoS/gEtty ImAgES

September 5 — September 11, 2011

Bloomberg Businessweek

the ground, and life insurance everywhere. But even Lloyd’s

lacked the imagination to anticipate September 11. “People

find it hard to believe in a risk unless they can see it in their

mind,” says Trevor Maynard, head of exposure management

for Lloyd’s. “When you try and describe a risk like this—some

terrorists are going to teach themselves how to fly a plane,

they will fly into property, the buildings will be weakened—by

the time you get to your third point, peoples’ eyes are glazing over.”

Floors 49 through 54 of the south tower housed Guy

Carpenter’s home offi ce and its 750 employees. To any of

Newhouse’s clients—insurers—professional employees in an

office tower would have presented an attractive bet in terms

of risk and reward. There are few slips and falls in white-collar

work and not much dangerous equipment lying around. Newhouse indulges in mild profanity and, thinking like a broker,

often lapses without warning into the voice of his customers

as they think about risk. “If I insure 40 of these firms in two

towers across 200 floors, probably the worst is that eight of

them, maybe six of them, could be involved in the same loss,”

he says. “Because the fire department can get there ... usually

a fire never spreads, historically, beyond six floors.”

The insurance industry describes these kinds of risks as

“high frequency”: The more often a kind of accident occurs,

the easier it is to guess its chance of happening and the easier

it is to price insurance coverage. For slips, lawsuits, and fires,

historical trends predict future probability. “What they hadn’t

imagined,” says Newhouse, picking his words carefully, “was

an intentional act of human causative agency.”

Guy Carpenter lost 29 employees on September 11. When

the plane hit his building, most of Newhouse’s employees were

well below him or out of the tower already. Guy Carpenter’s

chief executive officer had traveled to an annual conference in

Monte Carlo, leaving Newhouse as the most senior manager.

After American Airlines Flight 11 hit the north tower, he told

everyone to leave. The company had been in the World Trade

Center in 1993 when a bomb exploded below the north tower.

His employees did not need to be reminded that the world

was a dangerous place, even if the building’s collapse still lay

outside of the realm of imagination. By the time Newhouse

reached the plaza level, a cordon of police officers waited to

direct him through the mall below. When he got back to street

level both towers were still standing. The hole in the north

tower glowed, he says, like a dragon in a cave.

He saw the chaos on the ground beneath the towers and

looked for a Hudson River ferry. He had no trouble getting

on board; there was no rush. “There were people hanging

around,” he says, “working their cell phones and watching.”

They were still there in the streets, watching, when his ferry

backed out and the floors of the south tower began to collapse

and accelerate down. Until that second, they hadn’t believed

that anything more could happen to them. No experience of

fear drove them to get far away, as fast as they could, until it

was too late.

I was standing there, too. I survived by dumb luck.

for cyclonic storms. No, he explained, little of that value was insured. “Honestly,” said someone else, “I’ve never understood

why those people don’t just leave. It’s a dangerous place.”

By definition, reinsurers work at the edge of suffering, and

so have developed euphemisms to help them stand at a distance. A catastrophe is called a “loss event.” A catastrophe big

enough to affect several reinsurers is called an “industry loss

event.” Reinsurers both need and fear these. The first dedicated reinsurer, Cologne Re, formed after a fire leveled about a

quarter of the city of Hamburg, Germany, in 1842. A loss event

reminds insurers of the value of the product; reinsurers can

raise rates, and the higher rates attract new capital. According

to Dowling & Partners, an investment adviser for the insurance

industry, after Hurricane Andrew ran across southern Florida in 1992, eight new reinsurers entered the market, together

valued at $2.9 billion. Although hurricanes seem frequent, the

insurance industry defines them as “low frequency” events;

there are perhaps 10 a year and not tens of thousands. Unlike

car accidents, you cannot look at the last decade of hurricane

results and predict this year’s losses with any accuracy.

Andrew’s $25 billion in losses, along with the then-new

availability of cheaper computing power, helped push insurers and reinsurers toward computer-driven modeling, which

leaned on meteorology and seismology to more precisely

define potential losses by estimating storm paths and categories and fault lines and tremor strengths. The models are

sophisticated, but reality is wily.

After September 11, another eight new reinsurers followed

the higher rates and entered the market, together valued at

$8.6 billion. Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and Wilma lured five

more new reinsurers with $5 billion in capital. Between catastrophes, the new capacity drives premiums back down

➡

and reinsurers are forced to undervalue risks to stay in

61

In the fall of 1998 I started a job in New York with one of

the world’s largest reinsurers. Soon after, at a meeting in a conference room above Park Avenue, someone complained that the

market for reinsurance had gone soft. “What we need,” he said,

“is a good catastrophe.” It was a joke, but true, too. I offered

that a cyclone had hit Bangladesh and it had been an active year

Businessweek.com | 15

September 5 — September 11, 2011

Bloomberg Businessweek

“nothing SAyS there

CAn’t be 10 world trAde

Center eventS in A yeAr,”

SAyS trilovSzky.

“there CAnnot be A

mAthemAtiCAl model for

people like bin lAden”

be one of them. Most reinsurance treaties renew on Jan. 1 and

the meeting oriented itself around a new question: What do

we do on 1/1/2002? “There were 15 managers, all with a background in property,” says Trilovszky. “We had flip chart paper

and we put it on the floor. We were kneeling on the floor, working out concepts, brainstorming ideas … that was the Munich

Re strategy for terrorism risk in the first days after 9/11.” In

Could we intereSt you in A poliCy?

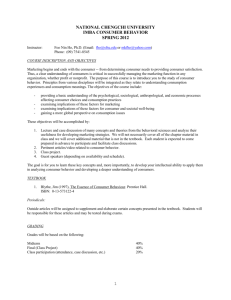

InSurEd loSSES*

BY caTEgorY

For the insurance industry at least, you can put a price on tragedy: According to

Swiss re’s catastrophe statistics, nature’s wrath and man-made disasters cost

society approximately $218 billion in 2010.

$80b

$40b

While the Indonesian earthquake

and tsunami of 2004 claimed more

than 220,000 lives, Hurricane

Katrina was far more costly to

insurers at $72.3b.

September11 cost

insurers around $23.1b

in property and business

interruption coverage.

2001

2002

2003

2004

$10b

Explosions or fires, including

at a sugar refinery, oil pipeline,

and mattress factory, amounted

to more than $5.3b in insured

damage.

2005

2006

2007

$1b

In the year that included Air

France 447’s loss over the Pacific,

insurers paid out around $2.1b in

transit damage.

2008

2009

2010

KEY: ● Storms/floods ● Earthquakes/tsunamis ● Transit/shipping/aviation accidents ● Major fires/explosions ● Terrorism/crime/misc.

16 | Bloomberg Businessweek’s Best of

*ProPErty And buSInESS IntErruPtIon, ExcludIng lIAbIlIty And lIFE InSurAncE loSSES dAtA: SWISS rE

62

the market. Vincent J. Dowling of Dowling & Partners refers to

this as the “cheating phase” of the cycle. That is, even though

catastrophes present an existential threat to insurers, and the

sober assessment of risk is a firm-defining competency, insurers, like people, can get complacent.

“The psychology piece dominates, even in boardrooms,”

says David Bresch. “People measure against the perceived reality around them and not against possible futures.”

Bresch is in charge of sustainability and risk management

for Swiss Re, founded in 1863 after a city fire in Glarus, Switzerland, and now the world’s second-largest reinsurer. “If the

gap between modeled reality and perceived reality is too big,”

says Bresch, “that tells you something about the market share

you’d like to achieve.” In other words, what the models show

as a best guess of a risk may not be what the insurers perceive

the risk to be, and it can take more than just data alone to scare

insurers into paying for risks at a rate that keeps reinsurers

solvent over the long term. That takes an industry loss event.

It takes a catastrophe.

Heike Trilovszky runs corporate underwriting for Munich

Re, the world’s largest reinsurer. The afternoon of September 11, the press and the company’s shareholders needed to

know what Munich Re’s losses would be. “To get answers we

had to ask the brokers,” she says. “Aon Benfield, Guy Carpenter, they had offices in those buildings. It was odd. Is my counterpart still alive?” Before the end of the week, Munich had

an initial estimate. In October, Trilovszky was at an off-site

meeting when a board member arrived late. He had seen the

revised loss estimate and he was pale. “We will survive,” he

said, “but it’s serious.” Munich Re’s losses after September 11

ultimately came to $2.2 billion.

Reinsurance treaties are full of exclusions, but before September 11 terrorism was not considered significant enough to

JIJI PrESS/AFP/gEtty ImAgES

September 5 — September 11, 2011

Bloomberg Businessweek

2002, together with the rest of the industry, the company They remind him when approaching a reinsurer about a client

wrote terrorism risk out of any treaty with an insured value to hear, speak, and say no evil. The monkeys are all gifts, given

of greater than $50 million. Terrorism is what Trilovszky calls to him to rebuild a much larger collection that was lost when

“nonfortuitous.” It stems from a few angry, motivated people, his last office disappeared.

and nothing says there can’t be 10 World Trade Center events

in a single year. “There cannot be a mathematical model,” she Swiss Re’s global headquarters face Lake Zurich, oversays, “for people like bin Laden.”

looking a small yacht harbor. Bresch and a colleague, Andreas

Reinsurers prefer to underwrite risks they

Schraft, sometimes walk the 20 minutes to the

can name; such a treaty is called a “named

train station together after work, past more

perils” cover. Far more often, however, the

yachts, an arboretum, and a series of bridges.

market forces them to sign an all-perils cover.

In September 2005, probably on one of these

Although reinsurers can exclude risks they alwalks, the two began to discuss what they now

ready know about from an all-perils treaty—an

call “Faktor K,” for “Kultur”: the culture factor.

act of terrorism, for example—they cannot exLosses from Hurricanes Katrina, Rita, and

clude what Donald Rumsfeld might call an unWilma had been much higher than expected

known unknown. That’s the God clause.

in ways the existing windstorm models hadn’t

Models exist for some low-frequency risks

predicted, and it wasn’t because they were far

Top 10 costliest

such as hurricanes, earthquakes, and oil spills,

off on wind velocities.

disasters Since 1970

but they don’t exist for every one. Trilovszky

The problem had to do more with how

①

doesn’t have a model for airplane crashes.

people on the Gulf Coast were assessing wind2011 earthquake,

“Would it hurt us if crashes became more frestorm risk as a group. Mangrove swamps on

tsunami, nuclear

quent? It would,” she says. “As it is now, I’m

the Louisiana coast had been cut down and

disaster

not sure we ever had a property loss from an

used as fertilizer, stripping away a barrier

$235 billion

Japan

aircraft crash. It’s theoretical. It lives within

that could have sapped the storm of some of

the error of the models we have.” The second

its energy. Levees were underbuilt, not over②

something unexpected happens, though, it’s

built. Reinsurers and modeling firms had fo2005 Hurricane Katrina

$72.3 billion

no longer theoretical or unimaginable.

cused on technology and the natural sciencu.S.

“The history of the industry,” says Newes; they were missing lessons from economists

house, the broker, “is we cover everything in a

and social scientists. “We can’t just add anoth③

1992 Hurricane andrew

catastrophe until after the catastrophe. Then

er bell and whistle to the model,” says Bresch,

$24.87 billion

we rewrite it.” Until the Sixties there was no

“It’s about how societies tolerate risk.”

u.S. and bahamas

hours clause—a time limit—on damage that can

“We approach a lot of things as much as

④

be claimed to be from a hurricane. Now the

we can from the point of statistics and hard

September 11

standard is 96 hours. Newhouse has been a redata,” says David Smith, head of model devel$23.13 billion

insurance broker for 35 years. Every new inopment for Eqecat, a natural hazards modu.S.

dustry loss event—every new catastrophe—is