The London Merchant: or, The History of George Barnwell

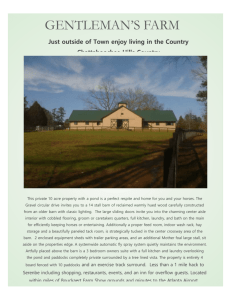

advertisement