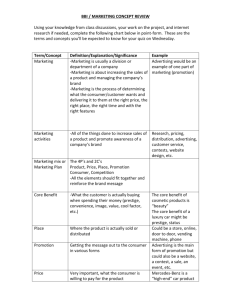

A model for predictive measurements of advertising effectiveness

advertisement

The authors describe a cammunicatian model for measuring the

flectkoness of advertising, Th;s

.?, :;t-~etcribes the process in

terms of a series of steps.

12

A model for predictive

measurements of

advertising effectiveness

Roberf J. Laviclge

and Gary A. Steiner

,,..

What arc the functions of advertising? Obviously the ultimate function is

to help produce sales. But all advertising is not, should not, and cannot be

designed to produce immediate purchases on the part of all who are cxposccl to it. lmmedi~te sales results (even if measurable) are, at best, an in. . . .,

complete criterion of advertising effectiveness.

In other words, the effects of much advertising are “long-term.” This

is sometimes taken to imply that all one can really do is wait and see—ultimately the campaign will or will not produce.

,l-lowever, if something is to happen in the long run, something must

,,

bc happening in the short rim, .something thrst will ultimately Icad to ?

5

cvcntua] sales results. And this process must be measured in order to pro<

vidc anything approaching a comprehensiv~ ~hti~~f the effectiveness J

( of the advertising.

<P Ultimate consumers normally do not switch from disinterested indi-’>

;) Vlduals to Convinced Pllrchascrs in one instantaneous stcP” Rather? theY

approach the ultimate purchase through a process or series of steps in

‘, which the actual purchase is but the final threshold.

/

...4....,,,,., >, ~

k? “:

Cn

‘1

“

+

Reprinted from the )ournal of M~rketing, national quarterly publication” of the American Marketing Ass(~ciotimr (October 1961), pp. 59-62.

(

137

I

138

Applications in marketing reseorch

seven steps

.“ >..’$s~?k+

Advertising may be thought of as a force which must move people

up a series of steps:

Near the bottom of the steps stand potential purchasers who are

completely unuwure of the existence of the product or service in

question.

Closer to purchasing, but still a long way from the cash register,

are those who are merely ~wure of its existence.

Up a step are prospects who kmw what the product ha to ofler.

Still closer to purchasing are those who have favorable attitudes

toward the product—those who like the product.

Those whose favorable attitudes have developed to the point of

prejererrce over all other possibilities are up still another step.

Even closer to purchasing are consumers who couple preference

with a desire to buy and the conviction that the purchase would bc

wise.

Finally, of course, is the step which translates this attitude into

actual Purchu.se.

Research to evaluate the effectiveness of advertisements can be designed to provide measures of movement on such a flight of steps.

The various steps are not necessarily equidistant. In some instances

the “distance” from awareness to preference may be very slight, while the

distance from preference to purchase is extremely large. In other cases, the

reverse may be true. Furthermore, a potential purchaser sometimes may

move up several steps simultaneously.

Consider the following hypotheses. The greater the psychological

and/or economic commitment involved in the purchase of a particular

product, the longer it will take to bring consumers up these steps, and tbc

more important the individual steps will be. Contrariwise, the less serious

the commitment, the more likely it is that some consumers will go almost

“immediately” to the top of the steps.

An impulse purchase might be consummated with no previous awareness, knowledge,, l~kin~ or conviction with respect to the product. On the

other hand, an ihdustrbl good or an important consumer product ordinarily will not be purchased in such a manner,

(“.

A model for predictive measurements of advertising et?eetiveness

139

to move people up the final steps toward purchase, At an extreme is the

“Buy Now” ad, designed to stimulate. ~ overt action. Contrast

this with industrial advertising, most of which is not intended to stimulate

immediate purchase in and of itself, Instead, it is designed to help pave the

way for the salesman by making the prospects aware of his company and

products, thus giving them knowledge and favorable attitudes about the

ways in which those products or services might be of value. This, of course,

involves rnovcmcnt up the lower and intermediate steps.

Even within a particular product category, or with a specific product,

different advcrtiscmcnts or campaigns may be aimed primarily at different

steps in the purchase process—and rightly so. For example, advertising for

ncw automobiles is likely to place considerable emphasis on the lower steps

when ncw models are first brought out. The advertiser recognizes that his

first lob is to make the potential customer aware of the new product, and

to give Ilim knowledge and favorable attitudes about the product. As the

year progresses, advertising emphasis tends to move up the steps. Finally,

at the cnd of the “model year” much emphasis is placed on the final step

—the attempt to stimulate immediate purchase among prospects who are

ass(mlcrl, by tbcn, to have information about the car.

‘1’IIc simple morfcl assumes that potential purchasers all “start from

scratch.” EIowever, some may have developed negative attitudes about the

product, which place them even further from purchasing the product than

those completely unaware of it. TIIC first lob, then, is to get them off the

negative steps—before they can move up the additional steps which lead

to purchase.

three functions of advertising

‘IIIc six steps outlined, beginning with “aware,” indicate three major

v

f(lllctions of advertising, ( 1 ) The first two, awareness and knowledge, , ~z

relate to inlorrnution or ideus. ( 2 ) The second two steps, liking and prcf- i

ercnce, have to do with favorable uttitudes or feelings toward the product.

(3) ‘l’he final two steps, conviction and purchase, are to produce uction–

the acquisition of the product.

I

“1’hcsc three advertising functions are directly,, related to a classic

psychological model which divides behavior into three components or dimensions:

1, “l’he cognitive component-the intellectual, mental, or “rational”

different objectives

Products differ markedly in terms of the role of advertising as related

to the various positions on the steps. A great deal of advertising is designed

sta tcs.

2. ‘1 ‘hc affcctivc component-the “emotional” or “feeling” states. ;

3. ‘1’bc conativc or motivational component–the “striving” states,

relating to the tendency to treat obiccts as positive or negative

\ goals.

.-c

S ~OAJfl S

ssaueJDMo puDJg

sanb!uqso+ OA!$>e!OJd

slo!\ueJejj!p

a!luowes puo 5+5 II

● SOIj>Jnd q uo!+ua~ul

senb!u~>et ● A!/3e!OJd

4!/!qoa!/ddv ~se~oe,ii

jo sde$s w pe+nlei

seqavoiddo qaioaseJ

jO sa\dunx3

su6!oduoa Jesoal

5U!J!JM Aqs

se[6u!r

SU0601S

SPO P!}!SSO12

s$ueue>unouuv

Ados eA!+d!J3sea

sloeddo JOIIIO[6 ‘snbo~g

SPO

eA!+!+ed~oD

Ado> eA!+O+UaUn6Jv

Slo!uou!+sel

sloeddo a>!Jd

sJejjo ,,a2uo~3-4sol,,

sloes

spo a40~s l!o+e~

eSOq>Jnd-jO-+U!Od

sde~s sno!JoA w $uoAe/el

6U!S!JJ&ApD JO uo!/owoJd

jo sed~ jo seldwnxa

1-Z1

379V1

P

NOI 1A ~

k.

{’4“

=SVH3Nnd

\e-o~~d ..–. . . . . .

\

pJOMO~

$uewaAow

laPOUJa~fO~ PS+O[aJ ~2JOaSaJ 6U!S!JJaAp0 PU06U!S!+leApv

..

—

“seJ!Sap JaaJ!p

Joa+olnw!~s spv .saA!+

7

-ow jo wlaaJ a~-eA!Jouo~ ,z,O’

...

Suo!suaw!p

/OJO!AOyaq

pa+ola~

.,

97

(

142

Applications in marke~ing research

A model for predictive measurements of advertising effectiveness

testing the model

Many common measurement of advertising effectiveness have been

concerned with movement up either the first steps or the fiml step on the

primary purchase flight. Examples include surveys to determine the extent

of brand awareness and information and measures of purchase and repeat

purchase among “exposed” versus “unexposed” groups.

Self-administered instruments, such as adaptations of the “semantic

differential” and adjective check lists, are particularly helpful in providing

the desired measurements of movement up or down the middle steps. The

semantic differential provides a means of scaling attitudes with regard to

a number of different issues in a manner which facilitates gathering the

information on an efficient quantitative basis. Adlectivc lists, used in

various ways, serve the same general purpose.

Such devices can provide relatively spontaneous, rather than “considered,” responses. They are also quickly administered and can contain

enough clcmcnts to make recall of specific responses by the test participant

clifficult, especially if the order of items is changed. This helps in minimizing “consistency” biases in various comparative uses of such mcasurcmcnt

tools.

Elliciency of these self-administered devices makes it practical to obtain responses to large numbers of items. This facilitates measurement of

elements or components differing only slightly, though importantly, from

each other.

Carefully constructed adicctive check lists, for example, have shown

remarkable discrimination between terms differing only in subtle shades of

meaning. One product may be seen as “rich,” “plush,” and “expensive,”

while another one is “plush,” “gaudy,” and “cheap.”

Such instruments make it possible to secure simultaneous measurements of both global attitudes and spen”fic image components. These can

be correlated with each other and directly related to the content of the

advertising messages tated.

Does the advertising change the thinking of the respondents with

regard to specific product attributes, characteristics or features, including

not only physidl c%;~kteristics but also various image elements such as

“status”? Are these changes commercially significant?

The measuring instruments mentioned are helpful in answering these

questions, They provide a means for correlating changes in specific attitudes concerning image components with cltanges in global attitudes or

position on the primary purchase steps.

143

:,. . , .;~,m

‘,

When groups of consumers are studied over time, do those who show

more movement on the measured steps eventually purchase the product

in greater proportions or quantities? Accumuktion of data utilizing the

stair-step model provides an opportunity to test the assumptions underlying the model by answering this question.

Three concepts

I’his approach to the measurement of advertising has evolved from

three concepts:

1. Realistic measurements of advertising effectiveness must be related

to an understanding of the functions of advertising. It is helpful

to think in terms of a model where advertising is likened to a force

which, if successful, moves people up a series of steps toward purchase.

2. Measurements of the effectiveness of the advertising should provide

measurements of changes at all levels on these steps—not lust at

the Icvcls of the development of product or feature awareness and

the stimulation of actual purchase.

3. Changes in attitudes as to specific image components can be evaluated together with changes in over-all images, to determine the

extent to which changes in the image components are related to

movement on the primary purchase steps.

I

(

The hypothesis of a hierarchy of effects: a pasiial evaluation

The a u t h o r exam;nes the widespread hypothesis in advertising

that a “’hierarchy of off ects” follows upon an individual’s perception of an advertising message and

before he buys.

I

Lavidge and Steiner claim that this sequence is based on what they term a

classic psychological model, which divid~.= into mgnitive, affective

and conative (or motivational) states.* “ ‘ ‘‘”

Ille Lavidge-Steiner hypothesis of a hierarchy of effeets offers in a

concise and clear manner viewpoints widely held in advertising circles for

many years. Attention, interest, desire and action [30]; awareness, acceptance, preference, intention to buy and provocation of sale [38];’ awareness,

comprehension, conviction and action [4] are but a few of similar but more

sketchy views of the internal psychological process a typical consumer is

supposed to experience from the perception of an ad to purchase; ‘“ ‘

Some recent refinements of the hypothe-sis are symptoms of its growing popularity. Copland, for instance, states that it cannot be expected

that a purchase will take place only if the individual has passed through

each of the stages of awareness, comprehension and conviction. Rather,

it is to be expected that some people who are merely aware of the existenee

of the brand will be buyers, rather more of those who comprehend the

message will be buyers, and even more of those who are convinced of the

truth of the claim will be found to be taking the final behavioral jump [5].

The broadly held agreement on this subject and the practical consequences which flow from this agreement provide an incentive to subject

the hypothesis to critical scrutiny. For if it is true that a one-way flow of

progression from message reception to overt behavior exists, then sales as a

.

13

The hypothesis of a

hierarchy of effects:

a partial evaluation

Krisfian S. PaIda

.

In 1961 Lavidge and Steiner presented a model for the predictive measurement of advertising effectiveness [12]. They postulated a hierarchical sequence of effects, resulting from the perception of an advertisement, which

moves the consumer ever closer to purchase. In diagram form the model is

as follows:

Movement

toword

purchose

Purchase

T

Canvictian

?’

Preference

?

Liking

‘r

Knowledge

‘r

Aworeness

criterion of effectiveness can be dispensed with and “substitute” variables

used instead.z It is notorious that sales measures of advertising effectiveness

are employed scantily, and a good case can be made for the claim that the

general acceptance of the idea of a hierarchy of advertising effects is to a

large extent responsible for this?

Voices of skepticism and dissent have not been entirely absent in

advertising literature [16]. Criticism seems, however, to have been directed

at each individual step in the hierarchy rather than at the hypothesis as a

whole.’ Furthermore: the criticism appears to have been predominantly

concerned with the methodological soundness of the research methods

employed to ascertain the effectiveness of an advertisement to bring about

.

Behavioral

Relotesf research

dimension

Cagnative-the realm

af matives

Split-run tests

Intention to buy

Projective techniques

Affective-the realm

Brand preference

mea sures

Image measures

Praiective techniques

Awareness surveys

Aided recall

‘“-”’”’~’’:~ematians

Canotive-the realm

of thoughts

Reprinted from the Journdl of M~rketing Resedrch, American Marketing Association

(February 1966), pp. 13-24.

144

145

I It is interesting to note that the branch of social psychology known as mass commuilications has not yet, with a single esception, offered s ~~thesis about the

decision prrrecss the individual goes through after the ~rception of an “actionoriented”

message. Mendelssohn [15] provides both the exeeption and a critique of mass comnrunications theory on this point.

z I have dealt elsewhere with the assertion that a firm ears find the optimum size of its

advertising appropriation, even though avoiding the use of sales as the ultimate yardstick of effectiveness [25]; it cannot.

~ A good example is the privately available [27].

4 In their recent book, Lllcas and Britt present a systematic evaluation of the research

methods dealing with each step in the hierarchy [14].

&

u

(

146

The hypothesis of a hierorchy of effects: o poriial evaluation

Applications in rnorketing reseorch

are obtained to the contrary, this is an assumption that advertising management and research personnel accept aud.y, mrrcludes Heller.

Such data to the contrary, in fairly per.suas}ve form and quantity, have

been assembled by Haskins [9]. He is interested ;rr the relationship between

factual learning and attitudm, or factual learning and sales. (This article

centers on the latter relationship. )

Haskins first surveyed those few private advertising research studies

which he could find. Two used sales as the criterion. In the first, awareness

was, but gain in knowledge was not related to increased sales. From tbe

second, which was a massive experiment, it appeared that knowledge was

not a prerequisite to sales, but attitude and belief changes preceded sales,

and there was a relationship between the two measures.

Searching through Psychological Abstracts for 1954-1963, he found 17

studies dealing with the correlation of knowledge changes with attitude or

behavioral changes. Two showed a positive relationship between changm in

knowledge/recall and the criterion variable (mostly attitudes ), two a negative relationship and the remaining 13 little or no relationship.

Against this evidence might be set the ancient popularity of Starch’s

service and his series of articles about Netapps [32]. Starch asserts that when

users arc divided into those who recall and those who do not recall tbe

arlvertisemcnt, the difference between them can be attributed to advertising. And that, typically, those who recall buy more than those who do not.

Rotzoll, in a recent summary of the usual objections to Starch, points

out why bigb purchase and high recall could both be present without one

necessarily being the cause of the other:

awareness, recall, attitude chang% etc. It has not tended to the question,

until very recently, the plausibility of assumption that each of these steps

contributes to an in~~ “@bability of purchase.5

In the following seetions, the assumption that movement up each step

of the hierarchy increases the probability of purchase on the part of a consumer will be critically evaluated, (The methodological soundness of the

various methods measuring the impact of advertising on the “intermediate”

variables will only & touched upon.) First, a survey of some of the literature and empirical evidence concerning the various hierarchical steps will

be made; second, an analysis of some data which have been gathered; third,

and finally, objections in the form of a table will be presented, and questions on the economic soundness of not using sales as the criterion of advertising effectiveness will be posed.

Published sources have been checked that would bc of relevance to the

testing of the hypothesis of hierarchical effects with regard to the link between each step and buying behavior. Confidence in this bibliographical

survey was strengthened when the bibliographical survey of the. Advertising

Research Foundation appeared and dovetailed with it [2].

Cogntiive dimensions

oworeness

Studies of change of awareness accompanying changed amounts of

advertising effort are so numerous that it is impossible to survey them. With

one exception, there is no good evidence that such changes in awareness

precede rather than follow purchase? Several studies, in which the relationship between change in awareness and change in sales was investigated,

in addition to other hierarchical eff ccts, are reviewed below.

knowledge,

147

recall ond recogntiion

The posit%#’@’6&~rtisers and their agencies with regard to measurement of awareness, recognition or recall was stated by Hcller as follows

[10]. Advertisers hypothesize that if advertising is to sell, it must communi,

cate, and that the ad that communicates best is tbe one that will produce

the greatest memory impression. Tbe assumption is that the memory production of an advertisement is related to its sales effectiveness. Until data

5 The important reeent exception is Haskins [9].

6 Tile exmption is [21], discussed later.

z“

=

a ) Product interest could affect willingness to be exposed to advertising

for a product;

b) Post-purchase doubts about the wisdom of choosing a product could

Icad to exposure to that prod~lct’s advertising in order to allay such

doubts;

c) “Yea-saying” tcndcncics may in ftatc readership-purchase correlation;

d ) Starch relics on the assumption, possibly unsound, that perceivcrsb~lycrs closely rcscmblc norrperccivcrs-nonbuycrs in all significant aspects except for exposure to the advertising message and purchase

of the brand [29].

1,1 /4. *,$.*.S*

To those objcctioos the following, from among many others, might

be added:

e) The possibility that many factors, other than the printed ad in question, were not eliminated from the test situation: frcqrrerrcy of exposure to previous ads of the brand, similarity to previous or other ads,

nurnbcr of claims in ad, etc.

f) l’urcbascrs of the brand may be better “rememberers,” because it may

bc easier to associate rcccnt cxpcricncc and recent perception.

(

148

The hypothesis of a hierarchy of effects: a partial evaluation

Apphccrt;ons hr marketing research

The methodological pitfalls surrounding recognition and recall tests

are discussed in Lucas and Britt [14].7

A search uneov~ th$”lol]owing studies in which recall is measured

against purchasing and which appear relevant to testing the hierarchical

hypothesis.

A study undertaken at Scott Paper deserves brief mention because it

claims to have used experimental methods to determine the relationship

between changes in recall, attitudes and market shares [28]. From the published report it is, however, impossible to determine with any degree of confidence what went on.”

NBC undertook an expensive study in the Davenport, Iowa, metropolitan area in 1952 to determine the effects of television viewing on purchasa [21]. A s~ial effort was made to find out whether viewing leads to

purchase, rather than purchase to the remembering of viewing.

Interviewed were 2,452 women, first in February and then in May, on

a particular T’V program viewed and the brand advertised. Table 13-1 was

TABLE 13-1

Respondents viewing a porticulor TV progrom end/or buying the brand

advertised, in February and May

BUYING

+-

-+

- -

Total

460

76

86

175

173

59

27

104

191

44

53

113

351

113

80

347

1175

292

246

739

797

363

401

891

2452

Viewing

++

++

+ -+

- Total

.

&urce: [21, Tssblo 5 in Appendix A].

constructed, where the first algebraic sign (+ or — ) refers to buying or

viewing in February, and the second to ‘buying or viewing in May.

Achi-square s~tistic of 89 calculated from this table points to a strong

relationship ~&h’ti&ing and buying.

7 Partierrlarly pp. 60 and 101. Note also their conclusion that @rt/olio tests of advertisements are so insensitive to changes in variables of interest as to be of little practical

value (pp. 77-78).

6 Thus, [or instanm, on page 66 it is stated that there was no advertising or promotion

in control markets (while test markets remived special direct mail advertising). But a

chart on page 68 gives an index of changes in recall of such advertising in control mar.

kets as well. A section heading is General Industry Awareness and Attitude Study, but

the word attitude cannot subsequently be found in the entire section.

149

If it were true that buyers are better rememberers of advertising exposure than nonbuyers, then it would,,.~

ble to expect that: (a)

c aim they started viewing

relatively more buyers than nonbuyers shoti~

T

between surveys; (b) relatively more buyers should claim they mntinued

to view the program. But the Davenport dab did not bear this out. Though

not conclusive, the evidence presented in this NBC study appears to indi- <

cate tha=ll

A SI- 1 ar study,

on magazine r~dership as well

- gathering

- Information

‘—

as television viewing, was reported by the project director for the NBC

Davenport study [3]. It appeared that TV viewing did, but magazine reading did not, contribute to an increase in sales. A subsequent critique by

Semen of this article points to some of the weak spots in this and other

NBC studies [31 ]. In particular, it attempts to show that the “start and

stop” viewing or reading analysis is of dubious value in this eontext.

Bridging the cognitive and affective behavioral dimensions is survey

evidence gathered by the NBC Hofstra television study [19]. Matched

panels of Ncw York metropolitan area television owners and nonowners

( 3,270) were interviewed about buying behavior on ho occasions, in January and May, 1949. The surveys covered purchases of brands advertised on

television and competing brands not on television, among such products

as gasoline, cigarettes, coffee, soap, watches, refrigerators. etc.

Most striking are the results of the semnd survey, which asked about

17 brands bought lately and about recent (last month) and remote (before

last month ) TV exposure. Table 13-2 summarizes the results. The base for

TABLE 13-2

Relative sales increases at various levels af expasure to TV advertising

(base o unexpected non-TV-owners)

Nonowner, seen TV

Total owners

Seen program recently

Seen program regulorly

Seen commercial recently

Liked commercial recently

1 2 . 8 %

41,7

54.9

59.6

64.3

I

,,,,,,L , *WV%:O:2

,.

Source: [19, p. 4 9].

the figures is the percentage of nonowners unexposed to TV who have

bought the brand in the past month: 23.5 percent. There appears to be a

steady progression in sales increases for ever higher levels of awareness, re- 1

call and liking of commercials.

(

150

The hypothesis of a hierarchy of effects: a partial evaluation

Applications in morket;ng research

Nevertheless, more detailed analysis shows that the memory ( cognitive) effect may be mo~e irn rtant than the liking (affective effect) of

E ousands of “likers” and “dislikers” intercommercials: of the ~i~

viewed; 34.5 percent who have seen the commercial recently and disliked

it, purchased the brand; only 33.8 percent of those who liked the commercial and saw it “remotely” did buy a brand [19, p. 42].

‘llle key issue in this study is how well the set owners were matched

with the nonowners. For every TV owner, a nonowner was obtained from

the same block, resembling the TV owner as closely as possible in family

composition and standard of living. Eleven variables were used in pairing

responclcnts. However, the fundamental question was not resolved: was

~not remembrance of advertising increased as a result of buying rather than

I!vice versa?

I

Af?ecfive

In any case, a very large number of attitude studies undertaken by

social psychologists are not concerned ,~~ntual prediction of behavior on the basis of ascertained attitudes. A~most 30 years ago it was

pointed o,ut that while critics deem the “merely verbal” aspect of attitude

mcasurcmcnt to be its Achilles’ heel, actions are no more “valid” inherently than words. Actions are frequently designed to conceal or distort

“true” attitude quite as fully as verbal behavior [18]. This caution about

tllc meaning and purpose of attitude measurement is not, however, observed universally either among psychologists or advertising men. As Festinger puts it:

What I want to stress is that we have been quietly and placidly ignoring a

very vital problcm. We have essentially persuaded ourselves that we can simply

assume that tberc is, of course, a relationship between attitude change and

(

\ subsequent behavior and, since this relationship is obvious, why should wc labor

to overcome the considerable technical dificrrlties of investigating it? But the

fcw relevant stodics certainly show that this ‘obvious’ relationship probably

dots not exist and that, inclccd, some non-obvious relationships may exist [8].

dimensions

Without question the strongest conviction held by the advertising

community with regard to the hi~rarchy relates to the ~nk bctwccn attitude (or change in attitude) and sale of the advertised product (or change

in sales).

What criterion, then, can be measured wllicll provides a predictive

151

COPY

test; what criterion is related to sales or brand usage? My answer is attitude

shift. . . . And why do I believe this? Because there is considerable and growing evidence that attitude shift is related to brand image; and because there is

an abiding logic backing up this evidence [1].

Is there such a logic; is there such evidence? There are really two

aspects to the problem of a link between attitude (or attitudinal change)

i~nd behavior (or behavioral change): ( 1 ) Is attitude a mechanism which

tends to direct behavior? (2) Must a change in attitude precede, rather

than follow, a change in behavior?

Consider the first aspect. Many psychologists have for a long time

been very careful about the definition of attitude.

Helen Peak dcscrvcs to

.

be quoted on ~$,@jcct:

Attitude is (defined as) a hypothetical construct which involves organization around a conceptual or perceptual nucleus and which has affective properties. . . . It is often said that an attitude is a “readiness for action” which

seems to imply that behavior is directly determined by attitudes. Wc regard

this at best as a greatly oversimpliticd statement of the relationship between

attitude and irction . . . an attitude should not bc expected to serve as an

adequate basis for predicting all behavior, since it is rarely more than one of

several components of motive structure [26].

It is symptomatic that “applied” social psychologists, working in fields

in which it is important to predict behavior, have been aware for some

tirnc that it is not easy to infer behavior from attitudes and vice versa.

‘1 ‘hc best summary of their thinking on this subject was recently presented

by Vroom [35]. 1 le points out that there appears to be no tendeney for

persons with prejudicial attitudes toward Negroes and Jews to express their

prcjurficcs when their interaction is within the eontext of a formal role

rclationsbip demanding a lack of discrimination. He also stresses that in

no sense should employee attitudes be regarded as causes of effective job

pcrforrnancc. 1 Ie argues that “the conditions which produce positive attitudes on the part of the employees toward their jobs are not necessarily

those that motivate thcm to perform effectively on these jobs.” Substitute

“consurncr, product, purchase” for “employee, job, perform” and the similirrity of this problem between industrial relations and advertising becomes

apparent.

Consicler now the second aspect. It is easy to imagine a purchasing

situation in which advertising, effective as a reminder of a particular brand

name, caused the consumer to select this rather, tiaa.~tier brand. Satisfaction with the consequences of the purchase evoked a favorable attitude

where none existed before, or strengthened a weak preference. That attitude change ean follow behavioral change is now widely accepted–the,

literature stretches from racial prejudice research to empirical studies of,

cognitive dissonance [6, 33]. Yet, there seems to be only one published

cmpirica] study of advertising effectiveness in which attitudes are measured nftcr exposure to advertising, but before any buying takes place, and

rnatcllcd against subsequent purcbascs [7].

I

152

Applications 1ss market;ng research

This should not imply that there are many published reports of

studi=delving into ~e.~~ent relationship &tieen attitude (change)

and buying (changer. fie~r ~ative scarcity is indicated by the fact that

of the 98 cases presented in the National Industrial Conference Board’s

monograph Mauring Advertising Results [22], only one makes some attempt in the direction of attitude—sales measurement (Case 35, Tea

Guncil of the USA).

te, cone and Belding designed to

DuBois reported on a study b

[71. Data were obtained On use

find out whether attitudes in fluen

and attitude for 40 assorted grocery store brands by 228 respondents in a

panel in one city. Most of the analysis was based on a composite of all 40

brands. which, when multiplied by 228 respondents, gave a total of 9,120

cases for the &mposite b r a n d ( X L ) .

Among users who called the brand “one of the best” at the outset, 68

percent continued using the brand. Among those who were only mildly

favorable, 50 percent continued using it. Among the handful less than

favorable, only 28 percent continued use.

Among nonusers who called the brand one of the best at the outset,

25 percent became users in the next few months, in contrast to 17 ~rcent

of those nonusers who had called the brand “good,” and nine percent of

those who rated it at anything less than good.

Both types of attitude effect, holding users and generating new users,

were observed to continue for a giderable -d of Wfter lwo

after a full year,

six months, and even [in a seDa

md of analysis of the same data, the 40 individual

brands were ranked according to- the percentage of users who called them

one of the best. ~wfound-that.the .higber thi~pro rtion, the higher

-the

alw.the-pr~p~tion dms-who+~

brands were reranked aarding to the percentage of nonusers who called

them one of the best. Again, the larger this percentage, the larger also was

the percentage of nonusers who became users within the next few months.

The study also provided evidence that changes in attitudes are conducive to changa in action. If the attitudes became more favorable, the

users were more likely to stay with the brand than if attitudes remained

mildly favorable. And, on the other hand, a deterioration of attitude

among users ~,.ta,lead to a falling off in the percentage of those remaining with the brarid. Similar effects of attitude change were observed

among nonusers. An increase in favorability went with larger percentages

of conversion. A decline in favorability of attitude led to lower perccntages of conversion.

Here the evidence, as reported, appears to bear out the idea that attiI

~ tudes do precede and causally influence buying. Unfortunately, the paucity

I1> of technical information (how were the observations pooled, what com-

The hypothesis of a hierarchy of Weets: a partiol evolution

153

posite measure constituted a “favorable atti~de,” how was the pretest

effect COp& with, etc. ) given in this ~-~ published in the proceedings of a conference precluda the thorough critique such a study

-.

would merit.

!(, :

A very interesting study of recall, association and, especially, attitude

change (as measured by the semantic differential), offering a wealth of

technical detail, was reported by

w 06] It stopped short, however,

of looking at purchasing behavior.

cvertheless, a brief passage from it

merits quotation:

From a research point of view, a further-reaching consequence was the introduction of more evidence s[lpporting the hypothesis that high levels of asso.

ciation or recall did not necessarily mean a favorable attitude or disposition to

buy the product. In addition, it seemed that high levels of recall did not even

necessarily mean that the consmncrs nndcrstood the core idea of intensive and

cxpcnsivc advertising campaigns [16, p. 371].

%“”. (;L 9;$-$@,qi,

Conative dimensions

intention to buy

There appear to be no published studies of the predictive power (with

r&gard to sales) of udverfking induced intentions to buy.o The classic

warnings about difficulties of using intentions to forecast sala, mncisely

uttered 15 years ago by brie and Roberb, are still valid [13]. The pro!

lcms faced in this area, but restricted to the relatively easier subject matter

of consumer durables, are exhaustively discussed by Juster [1 1].

More fhan one dimension

The following two studies which are briefly reviewed cover more than

onc behavioral dimension of the hierarchy.

At first sight, NBC’S Fort Wayne study [20] IOOh like a massive test

in which the hierarchy of effects is well ddtiheri~%~ “How television

works to condition customers all along the road to purchase is a research

area explored for the first time in this study. : . . It advances viewers

along every step in the creation of customers for a brand. It turns strangers

into acquaintances . . . acquaintances into friends , . . friends into cuss Wells and Dames drew attention to the effeet “cxaggeraton” might have on survey

resldts when bnth ex~~osure to media and intentions to buy are measured [37]. But this

problcm has no relation with the }licrarchy of effects.

(

154

Applications in marketing reseorch

tomers [20, p. 9].” After wading through the quagmire of results and technical appendim, it ~,rn~t,apparent that no such thing was documented.

Over 5,000 ho&%iv~ were interviewed in Fort Wayne in the Fall

of 1953 before the first local television station went on the air. They were

reinterviewed six months later. The emphasis was on respondents who

acquired a TV set between the two surveys. Some or all of the TV buyers

were measured on brand awareness, brand-product association, slogan identification, trademark recognition, brand reputation, or brand preference

with regard to abut 35 advertised brands and then compared to the “unexposed” respondents. There is little question about the sturdy increase

in the level of the “communications” variables among the set buyers as

opposed to those “unexposed.” However, information about percentage

changes in the various effects, Qrs.d the percentage change in purchases, is

given out on Scotties face tissues only; no mention is made of Halo in

this contex~ although all of the measurements taken on Scotties were

also taken on Halo; and the percentage change in purchases of other

brands is presented in aggregate form only. Scotties registered a net absolute increase (difference between set buyers and the unexposed ) in slogan

identification of 46 percent, in brand reputation of 6 percent, in brand

preference of 20 permnt. Characteristically, only the absolute increase (percent of set buyers who bought Scot ties during the last four weeks before

the second interview m“nus the percentage of the same interviewees who

bought Scotties in the last four weeks before the first interview) in

Scotties’ purchases is given— 20 percentage points. The increase in buying

in the control (unexposed) group is not presented.

Anyone who is seriously interested in the technical quality of advertising effectiveness research is advised to go carefully over this study, which

is ambitious, costly and typical.

A recent massive and analytically conscientious study, John B. Stewart’s Re~titive Arfvetiising in Newspu@rs [34], turned some of its attention to the hierarchical steps. Chapters 5, 6 and 7 are devoted to consumer

awareness of brands, Chapter 8 to product knowledge imparted by advertising, Chapter 9 to product images and 10 to purchase intent.

The book reports on a massive experiment in Fort Wayne, Indiana,

with advertising campaigns for two products. As usual, a higher level of

awareness and .b~ product knowledge was exhibited by purchasers than

nonbuyers; as usual there is no information on precedence in time, except

that “those who planned to try” scored about one-third higher on product

knowledge than those who did not. With regard to the attitude towards

the advertised products, Stewart says “Apparently product usage was a

more powerful influence on the image than was exposure to advertising

[34, p. 192].”

Intent to purchase was not matched with actual purchase. Five re-

The hypothesis of a hierarchy of effects: a partial evaluation

155

spondents out of the 1,314 subjecb who were not exposed to advertising

declared that they intended to purch~t~ product; of the 1,903 subjects who were exposed, 17 declared their readiness to buy one product,

and 27 declared intent to purchase the other product [p, 211]. After the

campaign ran for several weeks, however, the differences between the exposed and nonexposed groups tended to disappear,lo

In his concluding chapter, Stewart writes:

What means can management use to evaluate a specific advertisement? Judging

from this campaign, the only safe measure would appear to be trial purchase.

As a more thorough understanding of persuasion through advertising is obtained, it may become possible to evaluate advertisements accurately before

they are actually run. But it would not have been possible to do a good job in

evaluation with the ‘before purchase’ measures used in this study [p. 300].

Two private studies of advertising effect which throw some light on

the hierarchical hypothesis, are now analyzed; first, because they provide

an opportunity of looking at some length at original data, and, second,

bccallsc they are typical of many other unpublished research studies. The

first study attempts only to link awareness of product with purchasing, but

it gives a substantial amount of data. The second deals with many of the

hierarchical steps; the data, however, are not abundant.

‘Illc first study concerned a newly launched brand of a household

utility product, not a regularly purchased itcm, priced between $6 and $8,

which was to some extent functionally differentiated from other brands of.

the same product class. Three tc]cphone surveys were undertaken in

March, May and July of the same year. In March and July the same 39

mcclium-to-srnall sized cities from coast to coast were the locale of the

survey; in May, however, only 30 of them. The universe from which the

sample was taken were households listed in telephone directories; about

400 names were selected at random in each city’s directory on each occasion. I’bus, the sample had different subjects for each time.

First a question was asked designed to yield information about the

respondent awareness of the brand. Then a question was asked whether

the respondent purchased the product within the last three months and,

if so, which brand. The two variables in the ~tu,d~,~re awareness and market share, and arc expressed in percentages of total respondents. Information was also gathered about level of advertising activity (Table 13-3).

I

‘l’able 13-4 cross-classifies period-to-period changes in awareness with

changes in market share. Since x 2 based on the cross-classification of

10 The study did find that the advertising campaign for one product was successful and

that it probzbly was not for the otbcr; this, bowever, has no bearing on the subject of

this paper.

I

●

Applicot;ons in marketing research

156

TABLE 13-3

Market shares, awareness and advertising intensity in 39 cities disclosed

during March, Moy a-tiy *eys

City

Y,

Y,

1

6.3

1.4

11.8

2.7

1.9

2.2

15.1

12.0

6.6

6.2

11.8

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

1.5

9.4

4.8

9.9

7.5

2.8

11.5

6.1

10.0

14.8

6.6

2.1

9.0 .“

5.9

-.

7.3

8.7

8.0

11.1

9.9

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

12.8

20.5

11.1

15.0

12.9

1.6

5.7

17.4

21.1

9.6

5.0

15.3

7.4

18.3

13.8

6.9

3.2

23.3

11.9

8.7

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

19.0

25.6

9.3

21.2

23.7

25.0

21.9

9.4 ;,y a *.J?.? .

15.2

21.7

10.4

13.7

29.1

12.5

30.0

13.3

24.2

25.3

Y,

x,

x,

x,

D

3.9

4.1

5.3

6.1

6.2

6.3

6.7

6.9

7.1

7.4

14.4

5.6

11.3

8.3

7.4

11.4

10.8

11.0

12.8

12.4

13.8

..

9.4

13.1

8.1

11.7

9.1

12.8

12.3

14.7

14.8

13.0

1.5

0

1

1

1

0

1

1

1.5

1

7.5

7.8

8.4”

8.4

9.9

10.1

10.4

11.6

13.5

13.6

I

14.6

22.9

15.7

15.7

15.8

16.0

16.7

18.1

18.8

18.9

9.8

16.3

5.4

13.3

14.3

10.9

18.0

8.0

12.8

21.8

9.1

14.6’

9.9

10.6

12.4

14.7

9.1

13.9

18.3

13.3

18.4

13.8

19.6

18.8

10.6

18.9

12.6

14.4

27.4

1

1

1

2

1

1.5

2

1

1.5

3

15.4

24.8

7.7

20.7

25.0

9.8

18.9

35.2

16.2

22.5

21.5

19.6

11.8

23.8

23.7

14.4

15.9

34.4

14.3

23.6

22.2

18.7

21.8

23.6

30.8

17.9

25.2

31.8

23.0

29.3

4

1

3

1.5

4

1

3

1.5

3

3

19.0

19.4

19.8

20.0

22.2

24.7

25.0

28.6

29.2

24.9

15.1

27.3

31.4

15.4

29.5

29.9

35.1

19.5

32.5

30.2

25.7

30.6

35.6

29.6

33.8

40.0

43.5

31.5

4

0

I

1

2

1

1

1

3

13.4

22.2

35.7

34.5

22.9

37.0

27.1

36.1

28.3

Note: The Y’s r-present merke? shores in the various ci)ies In percentages. The

X’S afo percentages

(

J

of respondents in corresponding cities who are owore of the

b r a n d . T h e s u b s c r i p t s stand for the March (l), Moy (2) and July (3) surveys. D is

o variable w h i c h roprosonts six different levels 0 1 c o m b i n e d T V a n d newspoper

a c t i v i t y s u p p o r t i n g the brand in question in the various cities. The data ore ar ronged in ascending order of magnitude of Y,.

The hypothesis of a h;erarchy

of ef?ectst a part;al evaluotian

157

AX8 with AYE is equal to 5.9 (Xal,.W = 3.8), it appears that a relationship

between the two vanablm exists which U, ~j~butable to chance alone.

Further estimation of this relationship led to regrmion analysis.

TABLE 13-4

Number of changes in market shares and awareness from March-May to

May-June

Change in awareness

Change ;n

mark et share

-AX,

AX,

Total

AX,

-AX,

AX,

-AX,

AY,

5

2

2

0

9

0

2

7

AY,

4

1

---

-AY,,

12

Subtotal

4

2

AY,

-AY,

16

4

0

0

7

0

1

0

12

2

-AY,

Subtotol

Total

Note: W h e r e

A% e X;-l

6

8

14

18

12

30

,A~i = ~1 - Y1-l,

The following linear multiple regressions were run:

group i

a) Yi = f(Xl)

Y,= I(X, , D,)

b ) Y,= f(log X,)

Y,= f(log X, , D,)

c) log Y: = f(logxt)

log Y\ = f(log X,, D,),

,, ,; L>,?, *%,,.+

where t = 1, or 2, or 3 representing, respectively, data from the first,

second and third survey, and D/s are dummies representing four levels of

combined TV and newspaper advertising activity: D1 = 1 when D = 1,

otllcrwisc its value is zero; and, similarly, D2 = 1 when D = 1.5 or 2;

D, = 1 when D = 3 or 4. The values of these dummy variables do not

change from period to period to period.

(

The hypothesis of a hierarchy of effeets: a partial evaluation

Applicsst;ons in mrrrkotirtg research

158

The first three equations listed below show the three ‘&t” estimated regressions for the three time peri

“$.s for Y with subscripts t,

t + 1 and t + 2, respectively). This stit~ti

‘ includes not only, for inY

group ii

a) Yt+l = f(xt}.q-.~c:*i

Y,+, = f(x,+l, xt)

Y,+, =f(x,)

Y,+, = f(xt+l)

Y,+2 = f(xt+2 , Xt+l)

YI+2 = f(xt+z, Xt+l , Xt)

stance, the form Yt+2 = f(Xl+2), but also Y~+~ = f(Xt+~ , X1+l , Xt ,

D,) etc. The criterion for inclusion into this group was the size of the

standard deviation of regression residuals (also called standard error of

estimate ). This statistic is the one most closely associated with forecasting

performance–the smaller it is, the smaller the forecast -error is likely to

bc [23].”

Y,+l = f(Xf ,Dt) etc.

Subgroups (b) i.e., the semilogarithmic, and (c) i.e., the logarithmic,

versions, were also run.

(1)

...

group III

a ) Yt+l=f

Y,+l=f

Y,+, =f

(

(

2X,+1 + Xt

2

)

’

Subgroups (b) and (c) were also calculated, where Fisher’s term was

3 log X,+ z + 2 log Xt + 1 etc., but the denominator was not transformed.

log Y,+2 = —0.321 + 1.090 IOgxt+z

(:.099!

7.03?

ND39

. Not expressed in logs

R2 : 0 . 7 6 5 .

The following two regressions are also listed for further discussion:

group iv

Koyck’s distributed lag [24]:

a) Yt+I = f(Xc+l, Y:)

Y,+l=f(Xt+],Y~,D,)

Y,+2= f(xt+z, Yt+l)

Y~+z = ~(xt+2 , Y/+1”, D~).

Subgroups (b) and (c) were also calculated.

(4 *.J .“+*J,... . ;

group v

AY,+l = f[A(xt+l)]

,

(3)

)

6

)

3x,+2+2x~+l +xt, D, .

Y,+2 = f

6

)

(

\

>

Y,+l = -0.722 + 0.667 Xi+l

(0.078)

7.051

3.775

N=30

R’= 0.723.

3X,+2 + 2X,+1 +x,

(

Y,= –1.176 + 0.741 X~

(0.087)

7.444

4.391

N=39

R2 = 0.661.

(2)

2xt+1 + ‘t D,

2

159

where AYI+l = Yl+l — Yt, etc.

AY,+2= f[A(Xt+, )]

AY, +,= f[A(X,+l)]

AY, +Z= f[A(X,+z,Xt+l)].

All in all, 70 regressions were run.

(4)

(5)

Y,+Z = —26.793 + 27.031 log X ( + 2 + 6.013 log Yt+l

(2.834)

(4.354)

6.687

3.619

N=30

R2 = 0 . 7 2 7

Ay, + I = –1.470 + 0.896 AXI+l

(;.;;:)

6.289

Nx29

.

R2 : O.joo.

i,,

,J

.!S.*I*,;,,(<

How should these results be interpreted? These three consecutive surveys are in many ways typical of much commercial advertising research,

in that quite a few data are generated without a rigorous attempt at getII Y is tfre market share and X awareness in periods indieatcd by the subtipts; N is

sample size; Rz is the coefficient of multiple determination; the figures in parentheses are

standard errors of regression coefficients and tile figures on the last line below each regression are, respectively, the standard deviation of the dependent variable and the

standard deviatioil of regression residuals.

(

160

Applications in marketing research

ting unambiguous results. This was the reason why it was considered important to subject the data @a? figorous an analysis as Possible.

Just as the pre~ti~~i-square analysis indicated, the regression

results confirm the pr~nm of a strong concurrent relationship bctieen

I awareness and market share. One could have, however, more confidence

in the existence of a causal relationship flowing from awareness to purchasing, if two phenomena potentially obtainable from the data had been

detected. First, the presence of higher levels of advertising activity should

(

have strengthened the awarenas-purchase relationship. But regression

equations incorporating dummies, which represented varying levels of

advertising activity, were of a lower quality than those which ‘did not.

Second, lag correlations between awareness and market shar)would

give a better indication of the direction of the causal flow between variables. But regressions using lagged awareness, the more refined Irving

Fisher lag, or the sophisticated Koyck lag distribution simply did not fit as

well as those of the concurrent form. (See, as evidence, the “best” lag

regression shown above, Equation 4,) Even first differences performed

poorly (Equation 5 shows the best first-difference equation fitted).

Thus, it cannot be said that the data from these surveys confirm the

hypothesis that awareness tends to precede or even to contribute to rate of

purchase. They only show that higher awareness coexists with higher purchasing rata.

A few years ago a Canadian producer of a brand of a frequently purchased, very widely used, low cost consumer product started cosponsoring

a highly popular television program in a mrtain provinm. (The other

sponsor was not new to the program. ) While his sponsorship was new, his

brand was well established in that province, holding a market share of almost 20 percent. To assess the effativeness of his advertising venture, the

manufacturer’s marketing research agency conducted three telephone surveys.

The purpose was, roughly, to get information on the awareness of the

sponsor’s identity, on the viewers’ reaction to the sponsorship of such a

program, on the extent of recall of the commercials, on the attitude toward

the company and its products, and on buying.

The telephopc<in~ews took place in the four principal cities of the

province. The first one was staged just before the start of the telecasts, the

second four weeks later, the third lust after the TV series finished several

months later. Five-hundred different subiects were selected in each of the

three surveys by a random procedure from the telephone directory. Two

quotas were imposed: the subiects had to be users of the product (not the

brand ) and half of them had to be male. Thus, the universe was one of

product users. The sex restriction (achieved by alternately asking to speak

The hypothesis of a hierarchy of effects: a partial evaluation

161

to the housewife or the husband) probably had little distorting effect,

users and viewers not likely being-oq :i

“ori grounds-differentially

distributed between the sexes. The time ow

“, e survey was after 5 P. M.,

and three callbacks were made.

awareness of sponsorship

“Could you tell me what company, or companies, sponsor each of

the following TV programs (six programs, rotating in order) ?“

During the second interview, 23 percent of all respondents correctly

mentioned the sponsor’s name. At the time of the third interview 48 percent did. Among the users of tbc brand the percentage went from 33 to

57, among nonusers it increased from 21 to 46. The results do not appmr

1

to need further statistical analysis.

opinion of sponsorship

“As it happens, the telecasts are sponsored by Company A and B

(rotating company name from respondent to respondent). Are there any

comments you would like to make about either or both companies and

their sponsorship of the TV program?” The results arc set forth in the

following two tabulations. for brand users and those who are not ~ur.

cbascrs if the brand:

BRAND USERS

Fovoroble

Second survey

Third survey

Totol

(o) 44

Other opinion

opinion

persons

(C) 46

—

90

(b)

60

(d)

71

Total

104

(n,)

(n,)

117

%

i

z = - . S9

USERS OF OTHER, ERA,NDS

survey

Third survey

Second

Totol

Favoroble opinion

Other opinion

Totol

186 persons

184

210

lW

396

383

G

G

z = .23

—

779

(\

162

The hypothesis of a hierarchy of effeds: a partial evaluation

Applications in madeting research

The analysis of the differences between proportions follows Wallis

and Roberts [36]. The follo ,~g statistic, z, is computed and reference is

made to the normal disbiiron tablg:

It is apparent that analysis of the total sample (500) will not yield a

higher value of z.

163

For the change recorded from the first to second sumey, it is clear that

since the two subgroups’ z statistic exceed, ~.the z statistic for the whole

,,

group will also.

For the change recorded from the second to third survey, the change

is clearly of little significance among brand users-5 t3-57 percent. This

small amount of change is enough to swamp the change among nonusers.

TABLE 13-5

Attitudes toward sponsor as indicated by respondents’ opinions obout

faur campanies, including the sponsor

recall of commercial cantent

PERCENT OF RESPONDENTS MENTIONING SPONSOR

“Let’s discuss . . . telecasts. Think back to the last few TV programs

and describe the [first/semnd] commercial you can remember. . . .“

ATTITUDE TOWARD

COMPANY

Sponsor’s

All re-

brond users

123

RESULTS FOR ALL RESPONDENTS

Second survey

Third survey

11%

20

52

Sponsor’s commercial

Recoiled first

second

20

Most progressive

Best reputation

Most community minded

Most interested in his

customers

Most popular

High quality products

Fostest growing

~ese figures do not need further statistical analysis.

Most reliable compony

Independent compony

Average

atiitude toward company

“I am going to read a list of descriptions and for each one, would you

please name the one of the four manufacturers that it best fits. If you

think it describes more than one, name them.” (Rotate name of manufacturer; keep reminding respondents who the four manufacturers are. )

The z statistics appropriate to evaluate changes in attitudes toward the

company are given for the averages:

..%’.

.l

.{:

L

First

to second survey chonge:

Sponsor’s brond users

Other brond users

1.76

2.36

Second to third survey chonge:

Other brond users

All respondents

2.38

1.28

Nonusers

spondents

123

!23

40

46

18

54

46

56

‘ 41

72

48

62

30

64

11

16

10

29

13

22

13

39

15

27

13

39

17

22

12

34

20

29

19

46

40

63

38

57

38

52

78

40

72

61

50

78

37

71

69

11

30

10

27

13

12

34

15

38

27

15

45

14

46

40

17

36

16

33

17

20

43

23

53

21 19

45 52

34 47

44

58

57

17

24

28

23

31

23

35

17

45

35

I Iowcvcr, the amount of change recorded between the first and the

third surveys is considerable for all groups.

brand

usage

, , ,‘$ -$~-: “.

“Now, speaking about (’the product’ ) only, which brand of it do you

use mainly?”

‘Illc proportion of all respondents claiming to use sponsor’s brand

mainly iocrcascd from 19.0 percent on the first survey to 20.8 percent on

the second and 23.4 on the last survey. ‘rhe first change being a small one,

the change between the first and third surveys will be assessed.

‘rhc z statistic oscd to evaluate this change yields the value of 1.62.

It SI1OUICI be pointed out that the dcpcndcnt variable here is not

.

.

.<

.

sasoyaJnd

,,oslndus!,, jo walqoJd ayl

-DZ!U*40 ~UD

Uo!+

~’q IID 4D P0406

-!4SISAU! UOaq ~le2JO>S SDq

sclqolnpuou popu DJq OJ pJ05

-oJ +!* suo!+ua$u! pe>npu!

-6 U! S!\ J0ApD jO Jo#od OA!\J!p

4Jd ‘U06!q2!W jO &! SJOA!Un

‘iquo~ qsloasa~ 4aAJnS

a~ Aq patusiwn>op klaA!

-SSDW uaaq scJq spoo6 slqo

-anp Jawnsuo>

jo sassola oh

pJo6aJ qJ!A sAaAJns ~nq.o~

-uo!~ua~u!

jo

Jamod aA!~s!paJd

sAaA)ns

eldwos

uo!JD+aJdJa&ul

.[~l] S6U!

-UOaU1 S$! JO! AOljaq UO

sJajuo3 q3!qA A+!lopoul

,e..’

o

so Jo ‘JO! ADqSq 6u!l>aJ!p

ws!u Dq>aw D so Ja~!.s

paua!. a q sn+ AOUI apn~

-!$JV ‘JO! AOqSq paAa!qao

LpmJ10 a~ 0+ 6u!uDaw

aA!6 0+ saA4as puo PaAl OA

-u!

s!

•p~!uo” u! e6u0q2

O ‘tsJ!j sa6uoq> JO! ADqaq

j ! ‘puoq Ja~o a~ UO .JO!

-Aoqaq

(PIJOM

U!

u! a6u0qa asno> OJ

s ! ILI!D a~ ‘JsJ!j pa6uoq2

s ! apn+!$~o uaqM ‘paqs!n6

-U!JS!p aq UD> JO!ADq

loa4

UOq+ AJOJOJOq Ol U! ‘pUOIAOH

0! 6u!pJ02>0 ‘aAa!q>b OJ Ja!

-sDa uo!~o>!unwwo> q6n0JqJ

a6uc.qo apn~!t~o ‘.6.a) 6u!4+as

ssauloznlou ‘aldwDs jo ~![on~

u!4a*q>S

spu D1q 6u01uD

-aq pu. ap~!uo uaa~aq

d!qsuo!+olaJ

,6u!uoaw, o

p u o d!~suo!~ola, Iosnaa v,,

J>a>!pu! jo AJ!p!l DA

‘6u!uoaw jo ~![ouo!suaw!p!ufi

sasuaJajaJd puo

suo!hsanb

sLaAins

apn~!b~v

pJD*oJ

sapn~!+~v

~JajjO ,,pu DJquOu,, o

s ! snlnw!~s

~uoAalaJ uaqm

qanow jo pJOm Aq

spo 6UOUID a>ua~ajald

~noqo p!os aq 6u!wAu0 uo~

uo!4Du!uo4u02

‘aA!k>oIJ$D

Jajjo

j ! !stlnsai so!q s,add!l> uodno~

~!l!q W!joJd alq!ssod

j!a~ jo uo!~o>!pu!

a A ! 6 $Ou

s a o p sal!joJd jo uos!Jodwoa

!suo!u!do ou JO} a>uo*ol

-10 ou !saA!+>ajpo jo 4!4010d

IO!J

-uajajj!p 5!JuDwaS

6u!44as jo

ssaul DJn$ou ‘aldwos jo A+!lonb

JazAlouD

uIn860ad

puo~ Anq Q UO!4

.!sods!p

puo pD jo ~uau

.Aotua (>!+aqJsa)

- q

Uo!J>auuoa

“

taajja

uaa*

oloq !paq!l s! po

auo Isoal tD +DW uo!~dwnssv

1DS!601 ON

SPO Jo ‘0s

-! JoduIoa paJ!od

pus. 4! Jalu-jO-JapIo

spo uaehuq sa>ua

.JajaJd eqt jo 6u!q!l

S4SaJ

&! A!\!suas 0144!1

● A!i2ajjV

O!lOfiJOd

lo!aJ8wwos Jo ~uautas!~

,,sJaJaqwawai,,

-4aApD ● u o ay~ uDqh Jaq40 SJOJ

]m~aq

q Aow pUO~ jO SJDSDqJJnd

.% .Jqs

●

->oj jo uo!/ou!uI!la

.

•~aldwo>ul

llD2aJ

1uo!t!u60>a~

a! A,as-jlcs u! AIJDl

-flJ!~JOd ‘aw!~ jo uo!\>Dq

.<

.,

4uo>!j!u6!s AuD Aq ● soqs

. .. .

L -Jnd 5$! apa>ad OJ puoq

~ jo ssaua,oMo Joj ~!ssaa

-au lB3!601 ou ‘loJaua6 ul

+noIu jo pJOM jo

●

auanbasuos

:.

SO SS@UaJOmD puD 6U!S!$JaA

-po jo

●

>uanbasuo> so ssau

-OJD*O uaa~q uo!40u!u!Jas!a

●

AaAJns

-i

t

ssauaJo& puDJg

ldwq

●A

!$ !u603

;,

SSSU~OaM

q2J0esaJ

aA!JUOJS9ns

qsns u!

lj>Joasal

swlqoid Pahlosaiun ● uos

pwola. /o>!dAL

!Ij aq~ jo sessau~oam lo>!6010po~aw

s!saqtod.4q stsajjo-jo-Ay>JoJa

J~&OS UO!JOUIJ~U!

jO so/dwox3

p u o aii!~uo~sqns jo

Uo!suelu,lp

/o! JO! AD1/a8

AJOIUUInS v

9-C1 319V1

(

166

The hypothesis of a hierarchy of effects: a partial evaluation

Applications in marketing research

~,y’~k~ “;”’

First survey

Third survey

95

117

,’

Nonusers

405

383

Total

Soo

500

sales, but rather the number of respondents who say they use the sponsor’s

brand rnuirrly. This is far from a reliable revenue yardstick. Thus, it is not

possible to say whether, as a result of the advertising, revenue increased, or

users bought at a higher rate than previously while some new customers

were acquired, etc. It is only possible to say that among the total respondents, the number of users grew from 95 to 117 out of 500.

What overall mnclusion can be reached from this study with regard,

to the hypothmis of hierarchical effects? It is clear that many of the communication objectives of the sponsor were reached: awareness of his sponsorship increased strongly from the time the TV series started; recall of

commercial content was very good and increased considerably. Slightly

more ambiguous results were obtained when opinions were sampled. Some,

but only a small amount, of increase of favorable opinion towards the

sponsorship of the TV series (really, toward this type of advertising) was

registered. However, on the highest rung of the hierarchical ladder a considerable increase in favorable attitude toward the company was recorded,

especially between the first and third surveys.

No such clear<ut results were obtained with regard to brand usage.

Keeping in mind that brand usage is not a perfect substitute for sales, it

cannot even be said, at least on non-Bayesian grounds, that it show~d a

significant amount of change. Thus, while “significantly” large numbers of

respondents moved “up the hierarchical ladder” of awareness, liking of

the advertising and of attitudes, performance on the last “rung” is difficult

to assess. Add to this the uncertainty of the causal direction (awareness + opinion + recall + attitude ~ usage) and we end with an unsatisfactory feeling. At that, this study appears to have been a rather good

one, unwittingly perhaps, but nevertheless persistently testing the hierarchical hypothesis.

As a cone-.~rk, it is suggested that the only satisfactory and

lasting answer to the doubts or unwarranted assertions concerning the

hierarchical hypothesis would be a well-designed experiment. Only an experiment can approach the assessment of the direction in the causal flow

unambiguously. Many problems can be foreseen, especially with pretest

effects in such experimentation, but it is not the task here to advise on its

feasibility.

A table was constructed (Table 13-6), leaning on the Lavidge-Steiner

‘ representation, to point out in condcnscd form most of the substantive

167

weaknesses of the hypothesis of hierarchical effects. Singled out for inclusion are also certain methodological w

,, most of them not menm~i ‘ ed with ~ch step in the

tioned above, which appear to behierarchy. The considerable number of these methodologi~l problems,

quite apart from the substantive objections brings up forcefully this question: Is it, on balance, really more difficult and expensive to investigate the

direct link between advertising expenditure and sales, than it is to undertake research into each step of the hierarchy-even if the existence of u

hierarchy of effects were actually established?

REFERENCES

1. ACHEN~AVM, Alvin A., “Is Copy Testing a Predictive Tool?” Proceedings,

10fh Anrruul Conference ( Ncw York: Advertising Research Foundation,

1964) , p. 66,

2. Sales Measures of Advertising: An Annotated Bibliography, compiled by

L. Krueger and C. Raymond (New York: Advertising Research Founda/

tion, 1964 ).

3. C OFFIN , Thomas E., “A Pioneering Experiment in Assessing Advertising

Effectiveness,” Jourrrul of Marketing, 27 (July 1963), pp. 1-10.

4. COLEY, Russell H., &d., Defining Advertising Gods for Measured Advertising Results (New York: Association of National Advertisers, 1961), p.

55.

5. C OPLAND , Brian, “An Evaluation of Conceptual Frameworks for Measuring Advertising Results,” Proceedings, 9th Annual Conference (New York:

Advertising Research Foundation, 1963 ).

6. DEUTSCH, M., and COLLINS , M, M., Interracial Housing—A Psychological

Evaluation of ~ Social Experiment (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota

Press, 1951),

7. DUBOIS, Cornelius, “The Story of Brand XL: How Consumer Attitudes

Affcctcd its Market Position,” Proceedings, i Sth Annual Conference,

American Association for Public opinion Research, Public Opinion Quarterly, 24 (Fall 1960), pp. 479-480.

8. FESTINCER, Leon, “Behavioral Support for Opinion Change,” Public

Opinion Quarterly, 27 (Fall 1965), pp. 4~17.

9. HASKINS, Jack B., “Fact ual Recall as a Measure of Advertising Effectiveness,” )ourn~l of Advertising Research, 4 (March 1964), pp. 2-8.

10. [IELLER, Norman, “An Applicati&n of Psychological Learning Theory to

Advertising,” Journal of Marketing, 20 (January 1956), pp. 248-254.

11. JUSTER , F. Thomas, Anticip~tions-und Purchases ( Prince};n, N.J.: Princeton University Press, for the National Bureau of Economic Research,

1964).

12. LAVIDGE, Robert C., and STEJNER, Gary A., “A Model for Predictive

(

168

App/icat;ans in market;ng research

Measurements of Advertising Effectivenessfl )ournaf of Marketing, 25

(October 1961

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

’18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

), pp. 59-62.

James ~; ~ ~OSIERTS, Harry V., Basr”c Methods of Marketing

Research (New York: MeCraw-Hill, 1963).

L UCAS , Darrell B., and BRSTT, Steuart H., Measuring Advertising Electiveness (New York: MeCraw-Hill,, 1963).

MENDELSOIIN, Harold, “Measuring the Process of Communications Effect,” Public Opinion Quarterly, 26 (Fall 1962), pp. 411-416.

MINOAK, William A., “A New Tcchniquc for Mcas{lring Advertising Effectiveness,” Journal of Marketing, 20 (April 1956), pp. 367-378. -MOSCOVICI, Serge, “Attitudes and Opinions,? Annual Review of Psychology, 14 ( 1963), pp. 249-250.

M U R P H Y , C., MU R P H Y , L. B., and N E W C O M B, T. M., Ex~”merrtul Soci~l Psychology (New York: Harper & Row, 1937), pp. 909-912.

National Broadcasting Company, The Hofstra Study: A Measure of Sules

E~ectiveness of TV Advertising (New York: National Broadcasting Company, 1950).

—, Strangers into Customers (New York: National Broadcasting

Company, 1953 ).

—, Why SaZes Comes in Curves (New York: National Broadcasting

Company, 1953).

Measuring Advertising Results (New York: National Industrial Conference

Board, 1962).

P ALDA , Kristian S., ‘The Evaluation of Regression Results,” in Stephen

A. Greyser, cd., Toward Scientific Marketing, Proceedings, Winter Conference of the Amm”can Marketing Association, 1963, pp. 279-290.

—, The Meuauremerrt of Cumulative Advertising Eflects ( Englewood

Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1964), Ch. 2.

—, “Sales Effects of Advertising,” /ourti of Advertising Research,

4 (September 1964), pp. 12-16.

P EAK , Helen, in Marshall R. Jones, cd., Nebrasku Symposium on Motivation-l 955 (Lincoln, Neb.: University of Nebraska Press, 1955), pp.

151-152.

Program for Measuring the EfectiveneS of General Motors’ Advertising

(Probable date: 1963, 100 pages).

ROENS, Burt B., “’New Findings from Scott’s Special Advertising Research

Study,” Proceedings, 7th Annud[ Conference (New York: Advertising Research Foundation, 1961 ), pp. 65-70.

ROTZOLL & B4 “The Starch and Ted Bates Correlative Measures of

Advertising Effecti~eness,” Journal of Advertising Research (March 1964),

pp. 22-24.

S ANDACE , C. H., and F RYBURGER , Vernon, Advertising Theory and Pructice, 6th ed. ( Homewood, Ill.: Irwin, 1964), p. 240.

S EMON , Thomas T., “Assumptions in Measuring Advertising Effectiveness,” Journu[ of Marketing, 28 (July 1964), pp. 43-14.

STARCH , Daniel, Measuring Product SaZes M~de by Advertising ( Mamaroncck, N.Y.: Daniel Starch and Staff, 1961 ).

bRIE,

The hypotheses of a hierarchy of effects: o patiial evaluation

169

33. S TRAITS , Bruce C., “The Pursuit of the Dissonant Consumer,” /OUfnd/

of Murketing, 28 (July ]964), pp. 6

g ~; IVews@@s (Boston: Har34. S T E W A R T , John B., Repetitive Advefi’ti

?

vard Business School, 1964 ).

35. V R O O M , Victor A., “Employee Attitudes,” in George Fisk, cd., The Frontiers of Management Psychology (New York: Harper & Row, 1964),

pp. 127-143.

36. W ALLIS , Alan, and ROBERTS , Harry V., Statistics-A New Approach (New

York: Free Press, 1956), p. 430.

37. W E L L S, William D., and DAMES, Joel, “Hidden Errors in Survey Data,”

]ournaf Of Marketing, 26 (octobcr 1962), pp. 50-53.

38. W OLFE , Harry D., B ROWN , James D., and T H O M P S O N , C. Clark, Measuring Advertising Results ( Ncw York: National Industrial Conference Board,

1962), p. 7.