Understanding Texas' Child Protection Services System

advertisement

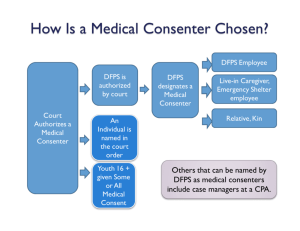

Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System April C. Wilson, Ph.D. Alaina E. Flannigan, B.S.; B.A. Sophie Phillips, LMSW Dimple Patel, B.A. Madeline McClure, LCSW Page |1 Child Protective Services (CPS) in Texas The goal of Child Protective Services (CPS)1 is to protect children from abuse and neglect by working with families to ensure safety, permanency, and well-being for children. Nevertheless, the rate of child maltreatment in Texas – and across the nation – remains high. Last year in Texas, 66,398 children were confirmed as being abused or neglected, and 156 children died from this maltreatment. Clearly more is needed to protect our most vulnerable population from harm. The high rate of abuse, neglect, and related fatalities leads many advocates and policymakers to examine the strengths and weaknesses of CPS to determine if reforms are needed. Having a firm grasp of the CPS process greatly enhances one’s ability to effectively advocate for change to the system. The purpose of this research brief is to provide an overview and detailed flowchart of the current CPS system in Texas. However, it is important to note that both the descriptive summary and corresponding flowchart reflect CPS policies that were current as of spring 2014 and may not reflect revisions or additions to policy thereafter. Additionally, due to caseload constraints, the outlined policies and procedures may not always be reflected in practice. Flowchart A detailed flowchart of the CPS system is available at the end of this document. The flowchart focuses exclusively on reports of child maltreatment (i.e., abuse, neglect, and/or exploitation of a minor (CA/N)) as potentially would be handled by CPS. The subsequent sections of this We need a comprehensive understanding of the CPS system if we want to effectively target strategies to enhance or improve the system. research brief detail each “stage” of the process from the time a report of child maltreatment is made to Statewide Intake until a case is closed by CPS. To note, CPS considers the way a child progresses through the system to occur in stages, and thus the flowchart is color-coded as such (e.g., all parts of Statewide Intake are green in filling and/or border). Boxes shaded in pink indicate a place in the process where a CPS case may close. This summary and the corresponding flowchart should be considered a template of the general pattern in which a child’s case moves through the system. However, specific features of each case may change this pattern. For example, a parent may be reported for neglect, but during the investigation, the caseworker observes signs of physical abuse; thus, a new allegation of physical abuse is added by the caseworker to the ongoing investigation (skipping Statewide 1 See the end of this report for a list of the acronyms used. Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 Page |2 Intake, unless someone outside the agency makes a separate report of physical abuse). Similarly, if a child is in a situation that could result in serious harm or death, this child may “jump” steps in the process to ensure safety (and possibly return to those steps later). Statewide Intake (SWI) Steps in the Intake stage are designated in green on the flowchart (or the border is in green in places where the case could be closed). SWI, a division within the Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS), operates 24 hours per day, 365 days of the year. It serves as the front door for processing all reports of abuse, neglect, or exploitation for the following divisions within DFPS: Child Protective Services, Adult Protective Services, and Child Care Licensing. SWI is responsible for: • assessing the information reported by applying state statutes and DFPS policy, • determining the correct DFPS program with jurisdiction to investigate, • entering the information into the automated computer system (IMPACT), • ensuring the report is processed and assigned to the correct DFPS program and local office, and Too Long to Wait? One consistent concern is that there are not enough SWI specialists to handle the large number of calls, thereby creating long hold times for those phoning in reports. The ongoing fear is that people not only hang up (i.e., abandon the call), but they also do not call back. Through legislative appropriations for more SWI specialists, the hold time and abandonment rate have decreased over the years from an average hold time of 10.6 minutes and an abandonment rate of 32.8% in 2009 to an average wait of 8.1 minutes with a 24.2% abandonment rate in 2013. Additional appropriation of SWI specialists from the 83rd legislative session should bring this hold time down even further. • serving as a referral center when information reported is not within DFPS jurisdiction. Reporters have the ability to contact Statewide Intake and make reports of abuse and neglect through different portals: the main abuse number (1-800-252-5400), the Community Center line (1-800-647-7418) for individuals in facilities that handle mental health, intellectual, or developmental disabilities, and through the internet (https://www.txabusehotline.org). Additionally, law enforcement has a prioritized toll-free line exclusively for their use in reporting. SWI provides translation services for reports as needed. The SWI division also operates a toll-free Texas Youth & Runaway Hotline to supply crisis counseling and referrals for troubled youth and families. Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 Page |3 SWI received a total of 731,156 contacts in Fiscal Year 2013 (primarily by phone or online reporting, but faxes also were accepted). When a report is made to SWI, an intake specialist collects a variety of information about the alleged abuse, neglect, and/or exploitation (see flowchart) to ascertain whether or not the report meets the statutory definition of maltreatment (Texas Family Code § 261.001). In 2013, almost 55% of the contacts did not meet this definition and often were referred to other services. In some cases, the contact to SWI is for a case-related special request (i.e., a request for CPS assistance); in these instances, CPS completes the request and the case is closed. Of the 334,798 reports in 2013 that met the definition of abuse, neglect, and/or exploitation, 229,334 (68.5%) fell under CPS jurisdiction. For these cases, the intake specialist assigns a priority level based on the assessed level of safety and severity of harm to the child. (i.e., Priority 1, Priority 2, or Priority None); these priorities provide directives for subsequent response. As a case moves from the intake to the investigation stage, CPS may reassess the priority. Priority 1 (P1) classifications are considered the highest risk cases and require an investigation to begin within 24 hours of the initial report. Cases are designated as a P1 if they involve: a child who seemingly faces an immediate risk of child maltreatment that could result in death or serious harm, subsequent reports alleging abuse or neglect that are received within 12 months after a previous investigation was closed as Unable to Complete (see investigation stage below for clarification on designations), and/or allegations that a child's death is related to abuse or neglect, even if there are no surviving children. In 2013, a total of 62,033 of the 229,138 (27.1%) reports were designated a P1. Priority 2 (P2) classifications include all other reports of abuse or neglect accepted for investigation. Investigation of P2 cases must begin within 72 hours of receiving the report unless eligible for screening by an investigation screener (Criteria for a formal screening can be found on the flowchart). Once an eligible P2 receives Priority Designation at Initial Intake PN 3% P1 27% P2 70% a formal screening and a decision is made by the investigation screener that an investigation is warranted, the case is stage progressed to Investigations, and the 72-hour Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 Page |4 initial contact timeframe begins for the investigative caseworker. In 2013, a total of 161,027 of the 229,138 (70.3%) intakes received a P2 designation at intake. Cases can be designated at SWI with the lowest level of urgency, a Priority None (PN), and not recommended for investigation if either of the following reasons apply: 1. Past Abuse or Neglect; No Current Safety Issues; No Apparent Risk of Recurrence in the Foreseeable Future. An intake qualifies for this code when all three of these criteria are true: a. The abuse or neglect happened in the past. b. There are no current safety issues. c. There is no apparent risk of recurrence in the foreseeable future. An incident of abuse or neglect would have met the legal definitions at the time the incident occurred; however, at the time of the report, there are no current safety concerns and no known risk of recurrence in the foreseeable future. 2. Additional Information From Specific Collateral or Principal (COL/PRN) Is Needed and Is Accessible to the Screener a. A key piece of information about the situation is missing but is needed to determine whether an assignable allegation of abuse or neglect exists. b. A specific collateral contact2 or principal is known to have the key piece of information that is needed and contact information for that person is available. c. The additional collateral contact or principal cannot be the reporter since they are presumed to have provided all known information at the time the report was made. Cases assigned a PN are routed to an investigation screener (technically part of the investigation stage). If the screener agrees with the designation of PN, the case is closed (in the Intake stage). Alternative Response If a PN or P2 case is routed through an investigation screener and closed during Intake, differential response may be provided. Differential response is designed to provide a less adversarial approach to ensuring child safety for cases in which there is a less immediate risk of serious harm. The goal in the current system is to notify (or attempt to notify) families about helpful community resources when closing a case without investigation. It is up to the family to use the recommended resources. In rare instances, a parent or caregiver may volunteer additional information about the allegation of abuse during the service call. In these occasions, 2 A collateral source is a person who assists CPS during the course of an investigation by providing information about alleged victims or their family members. A collateral source that assists CPS by providing information in good faith is immune from civil or criminal liability. Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 Page |5 screeners may discuss the case with their supervisor, and the case may be assigned to investigation. Legislation from the 83rd session allows for a more comprehensive form of differential response, alternative response (AR), to be established.3 Unlike differential response, AR is a new stage of service. Families that meet the criteria to receive AR will be provided with (voluntary) services to best address their unique needs and family strengths. More severe, higher risk reports are assigned to the traditional investigation pathway, while less severe, lower risk reports are assigned to the AR pathway. Unlike a traditional investigation, there is no final case disposition or designation of a perpetrator of abuse/neglect in AR. Consequently, no person is added to the central registry as a result of the intervention. Without the disposition requirement, the AR approach is designed to be less adversarial and more collaborative than a traditional investigation. Families who receive a formal investigation (and disposition finding) are ineligible to receive AR, but families in AR may be rerouted to the investigation (i.e., traditional) track at any point if the assigned caseworker believes there is a more serious risk of maltreatment than originally identified. Investigations (INV) Steps in the Investigation stage are designated in blue on the flowchart (or the border is in blue in places where the case could be closed). One of the primary purposes of investigations during the CPS process is to determine if a child has been abused or neglected (i.e., to assign a finding to the abuse/neglect allegation). Investigative workers also seek to identify whether there are any immediate – or longer term – threats to the safety of the child in their current living situation. If a threat is determined, CPS investigators must then decide whether the parents are “willing and able to adequately manage those threats to keep children safe” (DFPS website). The investigative screener may change the priority initially assigned by the SWI specialist. In 2013, a total of 66,717 cases were assigned to an investigative screener. Of those, 49,075 (73.6%) advanced to the investigative supervisor with a P1 or P2 designation, and 17,642 cases were screened out as a PN.4 3 The AR system was established by S.B. 423 (83rd R), which amends Section 261.3015 of the Texas Family Code. The initial rollout of AR is scheduled to begin in November 2014 in selected areas; it is anticipated to take 2-3 years for statewide implementation. Details of how AR will be implemented in Texas are being determined. 4 All closed cases must be designated with a PN. Therefore, some of the 17,642 cases closed at this stage were sent to the investigation screener as a P2 designation initially. Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 Page |6 An investigative supervisor in the appropriate region reviews all reports prior to assigning them to a caseworker for investigation.5 This supervisor can either close the case without an investigation or can assign the case to a caseworker for full investigation. In 2013, a total of 160,2406 cases had a completed investigation (out of the 205,418 P1 and P2 cases that advanced to the investigation stage). As part of the investigative process, the investigative caseworker ideally reviews all previous CPS history, conducts criminal history checks, calls the reporter for additional information and consults with his or her supervisor. The investigative caseworker can also coordinate with law enforcement (as needed) before conducting the initial interviews. If deemed necessary, a joint investigation with law enforcement can be completed utilizing one of the state’s Children’s Advocacy Centers (CAC).7 Next, the investigator typically will interview the alleged victim, other children and adults in the home, the alleged perpetrator(s), as well as other individuals who may know or have information about the family and family and set up a forensic interview at a CAC when deemed necessary. A home visit is conducted whenever necessary to assess child safety. The investigator is concerned initially with three things: 1. Is the child in present danger of serious harm (safety assessment)? 2. Is the child in danger within the near future (risk assessment)? 3. Did maltreatment occur (disposition assignment)? In cases where the child is threatened by immediate harm, CPS will immediately begin the process for removal or safety plan initiation, even if the case is still under investigation. In these situations, the child is essentially jumping ahead in the CPS process to ensure his or her immediate safety. In other cases where it is decided that the threat is not imminent, the risk assessment and investigation of possible maltreatment happen concurrently. The final ruling (disposition) of whether maltreatment occurred falls into one of two categories: abuse or neglect substantiated (confirmed) or abuse unsubstantiated (unconfirmed). For cases of confirmed abuse, the disposition assigned is: 5 Like the screener, the supervisor also can change the priority level. This total was calculated by summing the total number of P1s at intake (62,033), P2s with a child under age 6 or an open investigation (94,310), and P2s that advanced from the investigative screener (49,075). 7 Joint investigations utilizing a CAC typically involve sexual abuse, severe physical abuse, and child fatalities. In FY14, CAC’s statewide conducted a total of 30,467 forensic interviews and served 40,000 children through case management and therapy services. 6 Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 Page |7 Reason to Believe (RTB) – based on preponderance of evidence, child maltreatment did occur o In 2013, a total of 40,249 (25.12%) of all completed investigations resulted in an RTB (a total of 66,398 unique or unduplicated children were confirmed for abuse).8 In 2013, a total of 76,239 allegations were confirmed of physical, sexual, or emotional abuse, abandonment, medical neglect, physical neglect, neglectful supervision, or refusal to accept parental responsibility.9 These confirmations were spread across 66,398 children (some children were victims of multiple types of abuse/neglect). The types of abuse confirmed in these cases were distributed as such: Types of Confirmed Allegations of Abuse/Neglect in 2013 0.9% Physical Abuse 15.4% Sexual Abuse Emotional Abuse 7.9% Abandonment Medical Neglect 66.5% 6.2% 0.6% 0.2% 2.3% Physical Neglect Neglectful Supervision For cases of unconfirmed abuse, the disposition assigned falls into one of three categories: Ruled Out (R/O) – based on available information, child maltreatment did not occur o In 2013, a total of 100,390 (62.65%) of all completed investigations resulted in an R/O. Unable to Complete (UTC) – before a conclusion could be made, the family moved and could not be located or the family refused to cooperate with the investigation o In 2013, a total of 3,368 (2.10%) of all completed investigations resulted in an UTC. Unable to Determine (UTD) – no preponderance of evidence exists that child maltreatment occurred, and it is not reasonable to conclude child maltreatment has not occurred, and the family did not move or become unable to locate before the worker could make a conclusion about the allegation 8 Victims have been unduplicated by investigation state. Multiple children, such as sibling groups, may be involved in a case. The total number of children in confirmed investigations in FY 2013 totaled 100,861. 9 See definitions of the different forms of abuse at: https://www.dfps.state.tx.us/Training/Reporting/recognizing.asp or http://www.statutes.legis.state.tx.us/Docs/FA/htm/FA.261.htm. Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 Page |8 o In 2013, a total of 16,233 (10.13%) of all completed investigations resulted in an UTD. A case also can be closed because “information received after [the] case [is] assigned [to] investigation reveals continued CPS intervention [is] unwarranted,” but that action is uncommon in this stage and most commonly occurs before the safety or risk assessment. As stated previously, an assessment of risk - defined as the “reasonable likelihood that children in a family will be abused or neglected in the foreseeable future after the investigation is closed” - is simultaneously conducted with the disposition assignment to determine the risk of future child maltreatment. Cases are closed (and possibly referred to community resources/referrals) if the investigator determines: No Risk Indicated (i.e., no significant factors) – the caseworker finds no current factors that significantly contribute to future risk, or Risk Factors Controlled – the caseworker identifies risk in the family’s current situation or history but determines safety can be ensured through the use of services, interventions, or resources other than CPS A total of 108,259 cases were closed because no risk was indicated or risk factors were controlled (17,528 in confirmed cases; 90,731 in unconfirmed cases). Some cases do not require the completion of the risk assessment. A total of 22,567 cases in 2013 did not have a risk assessment completed (179 in confirmed cases, 22,388 in unconfirmed). Families are referred for services if the investigator determines: Risk indicated – the caseworker identifies risk in the family’s current situation or history and determines that the family cannot manage this risk without CPS assistance. A child can be considered at risk of future harm even if the abuse is unconfirmed (and vice versa). In 2013, a total of 29,414 cases were eligible for services because risk was indicated (22,542 in confirmed cases; 6,872 in unconfirmed cases). One of three things can happen when risk is indicated, and a case is eligible for services: 1. The case can be closed because the family refused services, was uncooperative, or moved and could no longer be located. A total of 1,529 cases closed at this point in 2013 (5.2% of cases eligible for services). 2. It is determined that the child can remain safely in the home either with services and/or if the perpetrator is removed. Most often, the family receives family-based safety services Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 Page |9 (FBSS) either voluntarily or through a court order if the family is unwilling, but the court deems such services necessary. 3. It is determined that the child cannot remain safely in the home. The child is removed from the home and placed in substitute care (i.e., SUB on flowchart – follow the “begin removal process” stage). If the child remains in the home during FBSS, the investigative caseworker will complete a transitional child safety plan. In actuality, this plan can be created at any point during the investigation stage, but it often is completed at this point. This voluntary safety plan is a written agreement between DFPS and the family that specifies the actions to be taken to ensure the immediate safety of the child until the FBSS family plan of service is completed (see FBSS / Family Preservation section). However, after the transitional child safety plan is completed, the investigator may decide that the family actually does not need services; in this instance, the case is closed before advancing to FBSS. Family-Based Safety Services (FBSS) Steps in the Family-Based Safety Services (FBSS) stage are designated in purple on the flowchart (or the border is in purple in places where the case could be closed). FBSS is the umbrella stage over Family Preservation (FPR) and Family Reunification (FRE). The goal of FBSS is to help families keep their children safe by providing services to help families build on their existing strengths and resources. Families usually (and ideally) live together in their home during FBSS (Family Preservation, FPR), but a parent may temporarily place the child with a relative or family friend when CPS determines that the child is not safe remaining in his or her own home. CPS may offer the parents the option of placing the child out of the home as an alternative to DFPS petitioning for court-ordered removal of the child. This voluntary placement by the parent is known as a parental child safety placement (PCSP). Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 P a g e | 10 Of the 27,885 cases opened for services in FY 2013 after completed investigations, nearly twothirds were referred to FPR services (19,999 of 27,885 cases (71.7%) involving 55,221 children). Because some investigations were completed in prior years, a total of 29,332 families actually received FPR services, which involved 82,017 children.10 The majority of children who received FPR services were able to remain safely in their home, however, 4,008 children ultimately were removed and placed outside the home because CPS determined a removal was necessary. An initial assessment of the family is performed within 10 business days of the FBSS supervisor’s receipt of the complete referral packet. Both the investigative caseworker and the FBSS caseworker participate in this assessment11 to (a) introduce the FBSS caseworker to the family, (b) ensure the information provided by the family stays consistent and up-to-date, and (c) allow the investigative caseworker to provide information about the family’s need for services. Within 10 business days of the referral being made, a staffing is held between the investigative caseworker, FBSS caseworker and/or their supervisors to determine if the case will be Removal of the Perpetrator Removing a child from his or her home can be an incredibly traumatic experience. This child, who already suffered from abuse, is now pulled away from all familiar support systems – his or her home, friends, school, etc. – and often left feeling stranded in unstable and impermanent placements with strangers. Thus, it makes sense to remove the offending adult from the home if a protective caregiver is able to remain. The perpetrator may voluntarily agree to temporarily leave the home, which is an option if the non-offending parent is willing and able to keep the perpetrator from returning. The removal of the perpetrator also may occur through the courts, such as when CPS petitions the court to grant a temporary restraining order (14 days). A temporary or permanent injunction removing the perpetrator may be pursued legally if the caseworker and supervisor feel that a longer duration is needed, but this option is rarely used. CPS does not currently track how often this option is used. Data from the Department of Public Safety shows that arrests for violations of orders decreased from 65 in 1996 to 3 in 2008 (with a steady decline starting in 2000). Of course, the arrest records could indicate either that people are not violating the orders as often or that orders are not being enforced by law enforcement, but the dramatic drop suggests that the option to remove the perpetrator was used more frequently in the past. accepted. It is possible for this 10 19,999 families entered FPR services in 2013 as a result of completed investigations during FY 2013. However, a total number of 29,332 families and 82,017 children received Family Preservation Services in 2013. Some of these cases were the result of completed investigations in a prior FY. 11 Unless both types of caseworkers attend the optional family team meeting, in which case investigative caseworkers do not have to participate in the family assessment. Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 P a g e | 11 assessment to result in a decision to close the family’s case on the basis that no services are needed, but this does not happen often. Families are assigned one of three intensities of FBSS according to the likelihood that a child in the family will be abused or neglected in the foreseeable future. Higher-level services often are needed when the family’s circumstances increase future risk, such as when a child is more vulnerable (for example, a child age 5 and younger) or when parents have serious insufficient protective capacities (for instance, when the parents are teenagers themselves or have intellectual or developmental disabilities). In all of the phases below, CPS aims to ensure that the child remains safe without CPS assistance after the case closes and help parents build on family strengths and resources to reduce the risk of future abuse or neglect. However, the amount of face-to-face contact, duration of services, and other specific service goals differ depending on the intensity level. It should be noted that the guidelines for ideal contact amounts are from the CPS Handbook, but the actual frequency of visits may differ in practice. Regular FBSS helps parents reduce the risk of future maltreatment within 180 to 270 days; it is required that caseworkers meet with families face-to-face at least once a month. Moderate FBSS is for families who are at a higher risk of abusing or neglecting their child than families in regular FBSS. An additional goal in this level is to protect a child from immediate risk as well as future risk within 90-180 days; it is required that families receive face-to-face contact at least three times a month. Intensive FBSS is provided to families that need the most assistance to protect a child from maltreatment in the immediate or short-term future with services that are likely to reduce the risk in 60-120 days. Caseworkers must visit with families at least twice per week at this intensity of services. The alternative to this level of service is obtaining a court order to remove a child from the home. Additionally, the family team meeting and family group conference can occur during this stage. The family team meeting involves a small group - typically only the family and relevant investigators – and is FBSS is Versatile designed as a rapid response FBSS can include many different types of services to short-term (or immediate) to families, depending on their needs. Families safety and placement concerns. A total of 9,164 may receive classes on parenting and family team meetings were housekeeping skills, substance abuse treatment, held across Texas in 2013. By anger management, nutrition and financial contrast, the family group education, or other skills training related to life conference is designed to management. Some of these services are empower the “family group” funded directly by DFPS, but many are funded with a high degree of by community-based and volunteer efforts. decision-making authority and responsibility to make long-term decisions about the family’s structure and well- Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 P a g e | 12 being. These meetings can include anyone who: is legally involved with the family’s case, the family wishes to invite, or CPS suggests (and for whom the family agrees). The family, CPS investigator, FBSS caseworker, CASA advocate, and attorney or guardian ad litem are among the usual participants. The family group conference is typically optional, but the meeting is considered ideal for all families. In Texas, 8,330 family group conferences were conducted in 2013. Through the services and various meetings, an FBSS family service plan is crafted within 21 days of the family’s referral to FBSS. This service plan is meant to: create a structured, time-limited process for providing services enable the family to enhance their own protective capacity of their child provide a safe home for the child as quickly as possible, and enable the family to function effectively without CPS assistance FBSS caseworkers review the progress made by families toward meeting the objectives from the family service plan at least once every three months. A case is typically closed once the family appears able to safely care for their child without CPS services. Whenever possible, the caseworker involves the family in the decision to close the FBSS case and tries to ensure that the family shares DFPS's belief that the family can manage the safety threats to the child without CPS assistance. All case closures require supervisor approval. If the family is unwilling or unable to keep the child safe despite the services received in FBSS, then removal of the child or court-ordered services may be considered. In 2013, the FBSS stage of service lasted an average of 7.3 months. A Simplistic View of a Child’s Journey Through Substitute Care Though this issue brief details the ideal plan for a child’s progression through substitute care, the reality for children often involves diverse obstacles. Children may have numerous adverse experiences as they adjust to their frequently changing living circumstances. Foster care and other substitute care options often are unable to adequately address the needs of these victimized children, and many children have multiple placements before attaining true permanency, which occurs once the child exists substitute care. Legislation and multiple reform efforts have been undertaken to improve the process, but advocates and foster youth continue to argue that much more is needed. Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org Substitute Care (SUB) Steps in the Substitute Care (SUB) stage, including the removal process to initiate SUB, are designated in yellow on the flowchart (or the border is in yellow in places where the case could be closed). Unfortunately, it often is necessary to remove a child from his or her home and place the child in the care of the state (i.e., substitute care) because it is believed the child cannot remain safely at home. The decision to remove a child can be made at any point in time (or in any stage) once an October 2014 P a g e | 13 investigation begins (for example, removal can occur at the start or end of an investigation, during FBSS, or during family reunification; see each section for more details). Of the 27,885 cases opened for services in 2013 after completed investigations, 7,886 cases (28.3%) resulted in removals and were referred to substitute care (involving 20,608 children). Of those 20,608 children in substitute care, 12,629 were removed from their home as a result of an investigation (although a total of 17,022 children were removed in FY 2013 from all stages of service).12 Substitute care is provided from the time a child is removed from his or her home and placed in DFPS conservatorship until the time a child exits substitute care. A removal normally occurs as a result of a court order, which is issued during an emergency hearing. If a child’s life is in danger or if he or she is at immediate risk of physical or sexual abuse, CPS can remove the child without a court order until the emergency hearing. The emergency hearing typically happens within one day of the removal (or suggested removal). At this hearing, DFPS must provide evidence that: there is a continuing danger to the physical health or safety of the child if the child is returned home, or there is evidence of sexual abuse and the child is at substantial risk of future sexual abuse; it is contrary to the child’s welfare to remain in the home; and reasonable efforts were made to prevent or eliminate the need for removal. A judge can then: order the case to be closed, agree that a threat is present but order the child returned home and order the family to complete services in FBSS, or agree that a threat is present and grant DFPS temporary managing conservatorship (TMC) of the child. Temporary Managing Conservatorship Temporary managing conservatorship (TMC) is an appointment by the court giving DFPS new legal roles over the child.13 As of August 2013, 59.5% of children under DFPS legal 12 The 20,608 children in substitute care includes all children in care regardless of victimization. This does not equal the number of children removed. 13 Texas Family Code § 153.371. These rights include: (1) the right to have physical possession and to direct the moral and religious training of the child; (2) the duty of care, control, protection, and reasonable discipline of the child; (3) the duty to provide the child with clothing, food, shelter, education, and medical, psychological, and dental care; (4) the right to consent for the child to medical, psychiatric, psychological, dental, and surgical treatment and to have access to the child's medical records; (5) the right to receive and give receipt for payments for the support of the child and to hold or disburse funds for the benefit of the child; (6) the right to the services and earnings of the child; (7) the right to consent to marriage and to enlistment in the armed forces of the United States; (8) the right to represent the child in legal action and to make other decisions of substantial legal significance concerning the child; (9) except when a guardian of the child's estate or a guardian or attorney ad Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 P a g e | 14 responsibility were in TMC. During TMC, a conservatorship (CVS) caseworker is assigned to the child. This caseworker creates a case plan to establish a structured, time-limited process for providing services to a child in substitute care and his or her family and to ensure that services and activities progress as quickly as possible towards the child's permanency goal. The case plan includes the child's service plan and, when applicable, the family's service plan. The (CVS) child service plan – which must be completed within 45 days after the initial placement into substitute care – details what services will be provided to the child, such as social, educational, medical and emotional healthcare, and placement plans. The (CVS) family service plan, which is created with the parents within 30 days of a child's placement into substitute care, outlines the services that parents should receive while their child is in substitute care (for example, addiction counseling). As soon as the State assumes custody and begins working on the case plan, the worker also looks for substitute care, which is a temporary home for the child. A child may be placed out of home in a kinship/relative placement, foster care placement, or in another arrangement. In 2013, children spent an average time of 6.8 months in the State’s TMC. If a child is unable to remain safely in his home of origin, the ideal placement for a child is in a safe kinship placement, either with a relative or fictive kin (a close family friend). Kinship placements typically offer the least disruption to a child's life, and a home study is done prior to the child's placement to help ensure the home is a good fit for the child. Another option is foster care, a label which can apply to many different types of homes, including: the home of an unrelated adult (child placing agency foster homes and DFPS foster homes) a group home where several foster youth reside together an emergency shelter a residential treatment center (RTC) for youth who may need special care and counseling Other placement options for children, especially older children, which do not fall under the umbrella of foster care or kinship care include juvenile detention facilities and independent living facilities where youth are provided services and guidance to assist them in transitioning into adulthood. In 2013, children who were ultimately emancipated had an average of 6.9 placements while under the conservatorship of DFPS and spent an average time of 55.6 (median of 43.1) months receiving services from DFPS. Children who were in other long-term substitute litem has been appointed for the child, the right to act as an agent of the child in relation to the child's estate if the child's action is required by a state, the United States, or a foreign government; (10) the right to designate the primary residence of the child and to make decisions regarding the child's education; and (11) if the parent-child relationship has been terminated with respect to the parents, or only living parent, or if there is no living parent, the right to consent to the adoption of the child and to make any other decision concerning the child that a parent could make. Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 P a g e | 15 care situations experienced an average of 2.1 placements and spent an average time of 17.1 (median of 7.6) months in care. An adversary hearing is held within 14 days of removing the child. Parents, caseworkers, and other adults involved in the child's life provide information about why they believe the child either can be returned home safely or should remain in substitute care. After hearing all the evidence, the judge may decide to close the case outright, order the child to be returned to the home for family reunification services (FRE), or grant CPS further managing conservatorship over the child because the home is deemed too unsafe to return. Custody under managing conservatorship obligate CPS to make more permanent, long term plans to secure the child’s future well-being. Where do children go in Substitute Care? Other Substitute Care Kinship Care 2% 4% Other Substitute Care 40% Other . 9% 5% 10% 90% Foster Care 3% 4% CPA Adoptive Homes DFPS Adoptive Homes Foster Care 60% CPA Foster Homes DFPS Foster Homes Basic Child Care 2% 71% Residential Treatment Centers Emergency Shelters Within 45 days after a child’s placement in substitute care (and prior to the 60-day status hearing), CPS files the family service plan and visitation plan with the court, which details the plans for service provision to a parent of a child in conservatorship and parents’ visitation schedule with a child, respectively. Within 60 days of issuing the order naming DFPS as the temporary managing conservator of a child, the court must hold a status hearing. The primary purpose of the status hearing is for the court to review the family service plan that was filed within 45 days of the child’s placement in TMC. Additionally, the hearing helps to ensure that parents are aware of the legal suit process Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 P a g e | 16 and understand the course of action for returning children back to their home. Prior to this hearing, CPS is responsible for submitting to the court any relevant child placement resource forms, completed home studies, names of relatives or caregivers who the child has been placed with, notification report to relatives about the recent removal, and copies of the visitation plan with either parent. The only exception in which the status hearing does not need to occur is in the event that the court makes the finding that no service plan is needed. Permanency From the point at which CPS assumes managing conservatorship of the child, the legal proceedings focus on finding a permanent solution that best addresses a child’s need for safety, permanency, and well-being. An initial permanency hearing is scheduled within 180 days after a child’s placement in substitute care and then held again every 120 days until the family is either reunified or until the final merits hearing. These permanency hearings, along with the permanency progress reports that are filed with the judge before every hearing, are designed to keep all involved parties appraised of how the child is progressing in substitute care and if the family is taking the necessary steps to improve and enhance their protective capacities to ensure the child can return home safely. Assuming the family is unable to keep a child safe, other permanency options are explored and pursued. In some cases, there is a mediation to resolve the legal case. If there is not a mediation, or if an agreement cannot be reached during a mediation, then a final merits hearing (typically after a year has passed) is held. During this hearing, both CPS and parents present arguments about what should happen next to ensure the child’s safety and best interests are taken into account. If the judge believes that living with the parents is the best option for a child, the case will be either closed or referred to reunification Where Do Children Go When They Leave DFPS Custody? services. If the judge determines it Aging Out 8% is unsafe and not in the child's best interest to return home, then one of two things can happen: • a relative is appointed as the child's permanent managing conservator, and the case is closed; or Nonrelative Adoption 15% Other 1% Family Reunification 33% Relative Adoption 15% Relative Custody 28% • CPS is granted permanent managing conservatorship (PMC) of child. CPS can be granted PMC of a child whether or not parental rights are terminated. Termination of parental rights makes the child eligible for adoption. Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 P a g e | 17 If CPS is granted PMC, the progress towards finding the best long-term living arrangement for that child is tracked at placement. If CPS is granted PMC with termination of parental rights, then the initial placement review hearing must be held within 90 days of the PMC order. After the initial 90 day hearing, placement hearings must be held every six months until the child achieves permanency. If CPS is granted PMC without termination of parental rights (which typically is disfavored and thus does not occur frequently), then the initial placement review hearings are held at least every six months until the child achieves permanency. Children spent an average time of 38.3 months in State PMC during 2013. While a child is in PMC, CPS continues to pursue permanency for the child. If CPS determines that a relative (or fictive kin) may be able to keep the child safe, that relative may be granted PMC of the child or may adopt the child. Children in the legal custody of relatives often have shorter stays in DFPS custody compared to the overall average (an average time of 19.1 months versus 34.1 months) as well as fewer placements (an average of 2 versus 6.9 placements). Parental rights, while retained initially under PMC, can be terminated so that a child becomes Average Number of Months available for adoption. How Long do Children Stay in DFPS Custody Before Leaving for Different Types of Care? 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 55.6 25.7 24.9 13.2 32.1 17.1 13.3 Family Relative Care Relative Care Reunification with PCA without PCA Relative Adoption Non-Relative Emancipation Adoption Other If CPS determines that it is unsafe or not in the child's best interest to return to a parent, and parental rights are not terminated, then the CPS may file to amend the current lawsuit and pursue termination of parental rights. Otherwise, if the parents are able to create a safe home for the child, and it is in the child's best interest, then the child may be reunified with their parent. However, if CPS is unable to identify a safe and permanent caregiver who is willing and able to take legal custody of the child, then that child may remain in foster care until he or she ages out of the system at age 18. In those circumstances, CPS attempts to identify a caring adult who is committed to supporting the youth as he/she transitions into and through early adulthood. For youth who age out of the foster care system, there is an option for them to remain in foster care through the extended care program, until the age of 21 (or 22 in certain Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 P a g e | 18 cases). There are certain criteria that must be met for a youth to be eligible for this program (such as attending school and/or working). If parental rights are terminated, status and placement review hearings will be held at least every six months. Once a permanent living situation is found for the child, and the matter of parental custody rights is settled, the case is closed. The child then may end up in a variety of living situations: • custody of relative • custody of unrelated caretaker • aging out of the foster care system at age 18 • alternative long-term living past age 18 • adult living (supervised independent living) if certain conditions are met past age 18 Family Reunification (FRE) Steps in the Family Reunification (FRE) stage are designated in orange on the flowchart (or the border is in orange in places where the case could be closed). Ideally, parents whose child is removed will work to ensure that they can provide a safe and stable home to their child in the future. Once parents make the necessary changes and demonstrate the necessary protective capacities to keep their child safe, the court may order that the child return to the parent's home. There is a transition and monitoring period when a child is returned home (as part of Family Reunification (FRE)). Specifically, families may become eligible for Family Reunification Services (FRS) if parents (a) have had at least one child removed, (b) have a reasonably stable living environment, (c) are working to complete the goals laid out in their CVS family service plan, and (d) have a target date set for the child’s return home (or the transition process has started already). In 2013, 63.8% of removed children were reunified with their family and had DFPS conservatorship terminated within 12 months of their removal. Families receive reunification services immediately before and after a child returns home from substitute care. The goal of these services is to provide support to families and children during this transition by: • helping families and children prepare for and adjust to a child’s return home, • helping parents build on their strengths and resources to reduce future risk of maltreatment to the child, and • enabling the family to protect the child without assistance from CPS. Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 P a g e | 19 There are different intensities (or levels of services) for FRE based on the degree of risk that returning home may pose to the child: regular, intensive early, and intensive. Regular and Maltreatment Recurrence Although the goal of family reunification is to protect children from future harm before closing a case, some who receive these reunification services return to substitute care. Of those families who were reunified in FY 2012, 16.4% of children were resubstantiated for abuse or returned to substitute care within 12 months during FY 2013. intensive are provided by substitute care workers unless otherwise determined by regional management. Intensive early services are provided by FBSS workers. The level of intervention needed may be ascertained during a discharge planning meeting, which happens during the 30 days prior to a child’s return home. This discharge meeting includes all parties involved in the case when possible (e.g., caseworkers, parents, children, extended family, attorneys ad litem, CASA volunteers, etc.). At this meeting, the CVS family service plan is updated with details for the reunification progress, and the child, family, and foster caregiver all are prepared emotionally for each of their respective transitions. This preparation for transition is essential because each party has adjusted – at least in part – to the current living situation. For example, the child may have developed a close bond to the foster caregiver, so it may be a difficult or bittersweet separation, especially if the child has been with the caregiver for many months or years. Multiple other challenges exist that may add to the complexity of the transition (e.g., mistrust of the system and or biological parents, etc.). CPS aims to continue providing support to the child and family throughout the transition, and the child may even make arrangements to stay in touch with the foster parents if he or she chooses. Families in all three levels of FRS intensity – Regular FRS (R-FRS), Intensive Early FRS (IE-FRS), and Intensive FRS (I-FRS) – receive visits in the home to ensure the child is safely and successfully transitioning into the home, and the parent has the necessary resources to support the child and safeguard child safety. The majority of children returning home receive the least intensive level, Regular FRS. These services are offered to children who have been in substitute care for longer than six months. These families should receive a minimum of one monthly visit from their caseworker. This level is ideal for families who thoroughly completed the steps detailed in their service plans and who maintained contact with their child during substitute care (i.e., close supervision by CPS is deemed unnecessary). The next level of service, Intensive Early FRS (IE-FRS), is intended for families whose child was in substitute care for only a brief period of time, such as a child who was returned home at the adversary hearing (which happens 14 days after a removal). These families are more intensely supported than those in R-FRS because the risk of future abuse/neglect may be higher in these cases, possibly because the reasons for the child’s removal are unlikely to have been resolved in the few days that have passed since the child was removed, and a court may have ordered this Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 P a g e | 20 child to be returned against the recommendation of CPS. To qualify for IE-FRS, the courts and/or CPS caseworkers must believe that intensive services are likely to improve the level of functioning in these families, and a plan must be in place to ensure the safety of the child. Typically, all children removed from the home are returned home at the same time when possible. On occasion, exceptions to these criteria can be made with court orders or as needed to address individual family needs. In IE-FRS, the frequency of the caseworker's contact with the family depends on the family's needs. Generally, contact is made at least weekly in the initial phase of reunification and then decreases over time as deemed appropriate to the case’s progress. However, contact must occur at least every thirty days while the case remains open. The highest level of service, Intensive FRS (I-FRS) differs from IE-FRS in that these families had their child removed for longer timeframes than those in IE-FRS (though other criteria for inclusion in this service level are similar) and have increased risk factors that require additional supports to safely and successfully transition the child back into the home. Depending on the length of time a child was in substitute care, these families may need additional support to rebuild family bonds. A child may have difficulty trusting his or her parents, and parents may need time to build or re-establish a healthy relationship with their child. In addition to home visits at least once a week, these families should receive a continuum of support through outside services with community agencies, CPS, and extended family support. After a child returns home, the reunification safety services caseworker and supervisor must review progress made toward the family service plan at least every 90 days; those in higher service intensities should have a plan review more frequently (and a more thorough review is conducted at six months for all families in FRS). The court system also reviews the progress of families in FRE during interim hearings, which are held every 60 to 90 days. The judge uses available evidence to decide whether to continue FRS. If the judge feels the family has made sufficient progress and no longer needs CPS support, he or she can order the case to be closed. If the judge believes the child is still unsafe and continued services are unlikely to keep the child safe in the home, the judge will order the child to be returned to substitute care. The legal case may remain open for an additional six months (120 days). If a case remains open for nine months or longer, the family must be referred to a family group conference (see FBSS stage for more details) as part of the plan for closing a case. Discussion Despite this relatively simplistic overview of the system structure, it should be evident that the CPS system as a whole is extremely complex in nature. That being said, the mission of CPS is simple on the surface: to protect children from abuse, neglect, and exploitation. CPS is designed as a temporary solution for families experiencing major dysfunction and challenges that extend beyond their capacity and/or resources to overcome. Unfortunately, the reality is that many Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 P a g e | 21 children spend their entire childhood growing up in a system that was never intended to replace parents. The CPS system in its current form cannot possibly provide all the resources or supports needed to help children realize their full potential. Ideally, the state response as a whole – including the child welfare system - should be designed to prevent children from being abused in the first place. Child abuse is a public health epidemic; it has been shown to cost the state and country billions of dollars annually, and the consequences for victimized children last a lifetime. For example, across their lifetimes, abused children are more likely to suffer psychologically (e.g., depression, anxiety, eating disorders, post-traumatic stress, etc.) and physically (e.g., asthma, high blood pressure, ulcers, heart disease, cancer, obesity, liver disease, etc.). Furthermore, with a growing child population, the state will continue to see an increased need for child welfare services in a system that already fights continuously for resources. The only way to get ahead of the problem and truly protect our most vulnerable population is through an emphasis on and investment in prevention. Families need to be empowered to provide the protective home environment that sets children on a path to long-term success. Although nothing can replace the role of a secure, safe, and loving family in a child’s life, the CPS system must still work effectively to ensure the best possible outcomes for our children and families who do enter the system. Texas has instituted multiple positive changes to the child welfare system and increased some funding toward this end, but the system lacks necessary resources to address the diverse needs of those under its care. More funding clearly is needed to protect children from current and future harm, but it also is imperative that the system be monitored so that it runs as efficiently as possible with its limited resources. The voices of those in the system – the children, parents, caseworkers, judges, CASA workers, medical and mental health workers and advocates to name a few – provide important insight into the sufficient amount and appropriate allocation of funding for services and support. Moreover, these voices add to an in-depth understanding of how the system should and does (or does not) currently operate. It is through this knowledge that one can make effective public policy changes that result in positive outcomes for our children and families in Texas. Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 P a g e | 22 References Used in This Report Include: Fang, X., Brown, D. S., Florence, C. S., & Mercy, J. A. (2012). The economic burden of child maltreatment in the United Sates and implications for prevention. Child Abuse & Neglect, 36(2), 156-165. Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., . . . Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. Perry, B. D. (2001). The neurodevelopmental impact of violence in childhood. In Schetky, D., Benedek, E. (Eds), Textbook of Child and Adolescent Forensic Psychiatry. (pp. 221-238). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. Springer, K. W., Sheridan, J., Kuo, D., & Carnes, M. (2007). Long-term physical and mental health consequences of childhood physical abuse: Results from a large populationbased sample of men and women. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31, 517-530. Texas Department of Family and Protective Services. (2013). 2013 annual report and data book. Retrieved from http://www.dfps.state.tx.us/documents/about/Data_Books_and_ Annual_Reports/2013/ FY2013_AnnualRpt_Databook.pdf. Texas Department of Family and Protective Services. (2013). DFPS program handbooks. Retrieved from http://www.dfps.state.tx.us/handbooks/. Texas Department of Family and Protective Services. (2013). Home page. Retrieved from http://www.dfps.state.tx.us/. Texas Family Code § 261.001. Additional documents provided by DFPS to TexProtects summarizing data book definitions, timeframes, CPS plans, and stages of service. TexProtects is extremely thankful to personnel at The Texas Department of Family Protective Services for their continual input to ensure the accuracy of the flowchart and report. We also greatly appreciate the work of our interns, particularly Jennifer Yates Lucy, for all their efforts in creating the flowchart. For More Information Dimple Patel dimple@texprotects.org 214.442.1672 ext. 675 2904 FLOYD STREET SUITE A DALLAS, TX 75204 Sophie Phillips sophie@texprotects.org 214.442.1672 ext. 622 t 214.442.1672 f 214.442.1644 TexProtects’ mission is to reduce and prevent child abuse and neglect through research, education, and advocacy. TexProtects effects change by organizing its members to advocate for increased investments in evidence-based child abuse prevention programs, CPS reforms, and treatment programs to heal abuse victims. Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 P a g e | 23 Acronyms in this Report and Flowchart Acronym AR CA/N CAC CASA CPS CVS DFPS FBSS FPR FRE FRS FY IE-FRS I-FRS R-FRS IMPACT INV P1 P2 PCSP PMC PN R/O R-FRS RTB RTC SUB SWI TMC UTC UTD Title Alternative Response Child Abuse or Neglect Children’s Advocacy Center Court Appointed Special Advocate Child Protective Services Conservatorship Department of Family Protective Services Family-Based Safety Services Family Preservation Family Reunification Family Reunification Services Fiscal Year Intensive Early FRS Intensive FRS Regular FRS Information Management Protecting Adults and Children in Texas Investigations Priority 1 Priority 2 Parent Child Safety Placement Permanent Managing Conservatorship Priority None Ruled Out Regular FRS Reason to Believe Resident Treatment Center Substitute Care Statewide Intake Temporary Managing Conservatorship Unable to Complete Unable to Determine Understanding Texas’ Child Protection Services System www.texprotects.org October 2014 Flowchart of Texas’ CPS System Abuse Allegation Filed with Statewide Intake (SWI) via Phone, Internet, Fax, Mail, Walk-in/Other Intake Specialist conducts an interview and initial assessment, obtaining information as relevant, and available, about the: a. Caregiver and alleged perpetrator (history/ability of caregiver; history of abuse, neglect, or exploitation) b. Victim and alleged perpetrator (history of abuse, neglect, or exploitation, mental/physical/medical disability, age, ability to protect self, access of alleged perpetrator to alleged victim, location) c. Alleged abuse, neglect, or exploitation (duration/severity, bodily injury or substantial risk of injury, type/location/degree of injury, length of time victim unattended, safety of surroundings) d. Resources available to the family e. General dynamics of the family (strengths and weaknesses) Case Related Special Request (request for CPS assistance: cannot be stage progressed & are closed after CPS completes request) Information and Referral Call (sent to open case, closed at SWI, or call maybe relevant to another agency) Allegation meets the legal definition of child abuse and/or neglect as defined in the Texas Family Code Yes Immediate risk of abuse, neglect, or exploitation that could result in death or serious harm, OR prior report closed as Unable to Locate within past year, OR allegation of child death from abuse or neglect? Yes Priority 1 (P1) 24 hours to Initiate Investigation Case Closed (As PN or Admin Closure) No Priority 2 (P2) 72 hours to Initiate Investigation Case Assigned to Investigative Supervisor in Appropriate Region No (Note: Supervisor can change priority) Priority None (PN: Not Recommended for investigation) Alleged victim > age 6 and with no open case (INV, FBSS, FSU, or FRE stages)? Yes Assigned to Caseworker for Investigation (Note: An investigator will typically respond to P1 cases before P2 cases, but child safety dominates prioritization) Case Assigned to Investigation Screener Investigative Process Before Initial Contact with Family, the Caseworker: Reads Intake for indications of safety and risk concerns Confers with supervisor to identify issues needing attention (throughout investigative process) May arrange joint investigation w/law enforcement (can occur at a Children’s Advocacy Center) Contacts reporter, if appropriate Checks Abuse/Neglect Backgrounds of Principles: o Alleged victims and perpetrators o Parents or legal guardians of child/victims o Caretakers o Other adults in the home Conducts criminal background check on alleged perpetrators and/or other adults Investigator Assesses: Patterns of maltreatment Previous home conditions related to serious harm of child Family’s ability to protect child from harm in past Child’s vulnerability to harm as result of previous home conditions Success of prior interventions and family’s response to interventions Previous investigations closed as Unable to Complete Investigator Interviews: Alleged victims and perpetrator(s), parents or legal guardians of child, caretakers, other children and adults in the home, collateral sources (i.e., school personnel, medical professionals, neighbors, friends, family members not living in the home, etc. Alternative Response Provided Details of Alternative Response Path TBD Case Closed/ Differential Response (services suggested) (Screened Out) Flowchart page 1 If Threat Currently Imminent: Safety Assessment (completed by investigator) (within 7 days after investigation is initiated, interviews/investigation may occur simultaneously) Determine present danger of serious harm, parents’ protective capacity, and ability to control risk with services Safety Plan or Removal (Risk Assessment will be conducted at some point) If child(ren) deemed safe right now Risk Assessment (completed by investigator) 7 Elements Evaluated to Ascertain Whether Child is Safe in the Near Future Child Vulnerability: fragility, behavior Caregiver Capability: knowledge, skills, control, functioning Quality of Care: emotional and physical care of children Maltreatment pattern: current severity, chronicity, trend of incidents Home and Social Environment: dangerous exposures in home, social violence issues present in home, including domestic violence Response to Intervention: caregiver’s attitude about CA/N, possible deception issues related to allegations Protective Capacity: factors and resources within the family that promote child safety Case Administratively Closed (uncommon here – normally before assessments) Unable to Complete: before conclusion could be made, family moved and could not be located OR family refused to cooperate with investigation Disposition Finding: Disposition Finding: Abuse Unsubstantiated Abuse Substantiated Ruled Out: based on available information, CA/N did not occur Unable to Determine: no preponderance of evidence of CA/N, not reasonable to conclude CA/N has not occurred, AND family did not move or become unable to locate Not Applicable in Some Cases (e.g. school investigation, death of only child; see 2327) Reason to Believe: based on preponderance of evidence, CA/N occurred Risk Assessment (when needed) and Disposition finding occur concurrently; Dispositions are informed by the investigative process and safety assessment Risk Finding Case Closed No Risk Indicated or Risk Factors Controlled, Child Deemed Safe (Family may be referred to other services) Conclusion: Child can remain safely in the home if the perpetrator is removed from the home Note: This option may occur in FBSS and requires a court order Conclusion: Child can remain safely in the home with services Families may participate voluntarily or by court order Transitional Child Safety Plan (Investigative worker must provide an active safety plan between DFPS and the family to ensure the immediate safety of the child in effect until the approval of the 21-day FBSS Family Plan of Service) NOTE: This plan can occur at any time during the investigation Refer to Family-Based Safety Services Risk Indicated (Child Unsafe); Family is eligible for services Conclusion: Child cannot remain safely in the home Begin Removal Process Case Closed Case Closed (Family Refused Services, Family Uncooperative or Family Moved) Investigative decision that family does not need services Flowchart page 2 Family Based Safety Services (includes FRE, FSU, and FRE) For some families, parents may be given the option to voluntarily place child with kin or fictive kin while receiving FBSS Parental Child Safety Placement (PCSP) Child remains in home under custody of parent Parent elects relative or close friend with whom CPS approves to place child (see Texas Family Code, Chapter 264, Subchapter L (264.901-264.906)) NOTE: This step also can occur during investigation Case Closed Family Assessment Done by investigative worker and FBSS worker together to do introductions with family and ensure info provided by family remains consistent. A staffing is held to determine if the case will be accepted. Regular FBSS Help parents build on family strengths/resources to reduce future CA/N risk within 180–270 days Face to face contact once a month Moderate FBSS Protect child from immediate CA/N risk Help parents build on family strengths/resources to reduce future CA/N risk within 90–180 days Face to face contact 3 times a month FBSS decision that family does not need services (this is uncommon) Intensive FBSS Protect child from immediate CA/N risk Help parents build on family strengths/resources to reduce future CA/N risk within 60–120 days Face to face contact twice a week Optional Meetings (can occur at different times in FBSS or in other stages and can be required to be offered in certain situations) Family Group Conference (required for some families, see 3341.1) Family Team Meeting Broad meeting that may include all legally involved parties such as family, investigator, CASA advocate, attorney or guardian ad litem Designed for making long term decisions Required for many families and ideal in all Small group, may be only investigators and family Designed to make immediate short term decisions FBSS Family Service Plan (within 21 days of being referred to FBSS) Development of a structured, time-limited process for providing services, enable the family to enhance their protective capacities, provide a safe home as quickly as possible, and function effectively without CPS assistance Case Closed Family follows plan and no longer needs services Ongoing Case Review Family fails to protect child or cooperate with CPS Request for Court-Order Services Begin Removal Process Flowchart page 3 Removal Process (under Family Substitute Care, stage) Possible Removal Pre-Hearing in Exigent Circumstances Case Closed Court Judge determines case should be closed FBSS Emergency Hearing to Determine Immediate Danger to Child (Within 1 Day) Threat Confirmed: CPS assumes Temporary Managing Conservatorship (TMC) of the child Threat Confirmed: Judge denies removal but orders services CVS Worker seeks Substitute Care (i.e., temporary home) for child This may occur simultaneously with case plan creation IDEAL IF FIT OPTION Out-of-Home Placement: Foster Care (Foster home, Group home, Emergency shelter, Residential Treatment Center (RTC), etc.) Court Ruling: Managing Conservatorship not granted to CPS, child returned home Family Reunification Services Out-of-Home Placement: Relative/Kinship Placement Out-of-Home Placement: Other Placement (Relative and Fictive Kin, Home study conducted prior to placement) (e.g., Runaway, Independent Living Programs, Juvenile Justice Department (TJJD) Placement) Adversary Hearing (within 14 days after removal) Court Ruling: Managing Conservatorship granted to CPS; child remains in Substitute Care Court Ruling: Dismiss the Case Case Closed Conservatorship (CVS) Case Plan & Visitation Plan Within 30 Days of Placement CVS Child Service Plan – written plan for services provided to child CVS Family Service Plan – written plan for services provided to parents Visitation Plan – written plan of visitation schedule 60-day Status Hearing Service Plan filed in court within 45 days and reviewed with Judge Flowchart page 4 Permanency Progress Report Filed no later than 10 days before each Permanency Hearing Child Safe to Return Home: Family Reunification Services Permanency Hearing First hearing within 180 days, then every 120 days until the Final Merits Hearing at the 1-year anniversary of TMC order (an extension up to 6-months may be granted in extraordinary circumstances) Child Safe: Case Closed Final Merits Hearing (trial) Child Safe to Return Home: Family Reunification Services Unsafe to Return Home: CPS given Permanent Managing Conservatorship (PMC) of child without termination of Parental Rights Placement Review Hearings (at least every 6 months until child reaches permanency) Unsafe to Return Home: Appoint Relative as Permanent Managing Conservator Unsafe to Return Home: Termination of Parental Rights; Child eligible for Adoption; CPS gains PMC Status and Placement Review Hearing (first hearing within 90 days, then at least every 6 months until permanency) Possible Outcomes: Possible Outcomes: Reunification Relative PMC Other Caretaker PMC Age Out of Care Emancipation Alternative Long-term Living Re-file Termination Grounds and Terminate Parental Rights Extended Foster Care until age 22 where applicable Adoption Relative PMC Other Caretaker PMC Age Out of Care Emancipation Alternative Long-term Living Supervised Independent Living Extended Foster Care until age 22 where applicable Case Closed Flowchart page 5 Family Reunification (FRE stage) Family Reunification Services (FRS) Goal: support the family and child during the child’s transition from living in substitute care to living at home Determine service level based on degree of risk in the home Goals for all plans: Ensure smooth transition by helping child and family prepare for return home Help parents build on family strengths/resources to reduce future CA/N risk Enable family to ensure child’s safety without CPS assistance after case closure Eligible families: Had at least one child removed from home Have a reasonably stable living arrangement Are working to complete Family Service Plan goals Discharge Planning Meeting – 30 days (or less depending on case) before child returns home Family Service Plan updated, child and family prepared for FRE, child and foster caregiver prepared for separation Intensive Early (IE-FRS) Regular (R-FRS) Visits occur at least monthly in the home DFPS conservatorship terminated no more than 6 months after child returns home Case Closed Judge decides child is safe Provided to families when a child was in short-term substitute care (often returned at the 14-day adversary hearing) Risk factors are high in these cases and intensive support services are needed Contact frequency depends on the family's needs. They may have many visits in a month but must have at least one monthly home visit Interim Hearings Check on family’s progress every 60-90 days Intensive (I-FRS) Provided to families when a child was placed in substitute care longer than a child in intensive early reunification Depending on length of time child was in substitute care, family may need various levels of support to rebuild the parentchild relationship Families should be provided continuum of resources through community agencies, CPS, and extended family support At least 1 weekly visit in the home Reunification failed Child deemed not safe and services deemed unable to keep child safe Return to Substitute Care Flowchart page 6