Class mobility across three generations in the US and - E-LIB

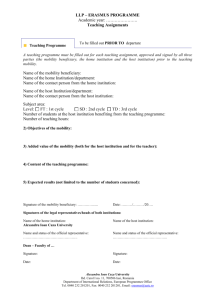

advertisement