Exploring the Political Diversity of Social Workers

advertisement

RESEARCH NOTE

Exploring the Political Diversity of Social Workers

Mitchell Rosenwald

barely audible conversation exists within

social work on the diversity of political ideology among social workers. Although diversity is a rich area of study in social work, a comprehensive exploration of social workers' political

ideologies remains largely absent (Rosenwald, 2004).

The assumption that social workers subscribe to

liberal economic, social, and moral values prevails,

as evidenced in NASW policy statements (National

Association of Social Workers [NASW], 2003), even

though this assumption has rarely been explicitly

and fully examined.This assumption occurs despite

the NASW Code ofEthics's, inclusion of respecting

fellow social workers' diversity of political belief

(NASW). As a result, ideologies of social workers

that differ from liberal political ideology may not

be represented.

A

The literature on political ideology provides some

insight into social \vorkers' political ideologies.

Political ideology, reflected in Democratic Party

membership, suggests social workers are predominantly liberal (Abbott, 1988, 1999; Epstein, 1969;

Reeser & Epstein, 1990). However, when ideology

was examined as political philosophy,findingswere

mixed; most social workers were liberal in Abbott's

(1988,1999) research but were fairly evenly liberal

and moderate (Hodge, 2003) or more moderate

(Varley, 1968) in other studies. Hodge also found

MSWs tended to be sUghdy more liberal than BSWs.

Social workers tended to be more liberal on general political ideology and specific policy positions

than people in other professions (Abbott, 1988;

Hendershot & Grimm, 1974;Jensen & Bergin, 1988;

Rubinstein, 1994) and the general public (Koeske

& Crouse, 1981; Hodge). Scant attention has been

given to studies involving social workers who idenPOLITICAL IDEOLOGIES

Political ideology refers to individuals' support of tify as radical left (but see Fisher,Weedman, Alex, &

Stout, 2001;Wagner, 1990) or radical right.

policy positions that reflect their attitudes on

society's relationship with technology, power disAlthough the literature provides a good introtribution, dependency, and nationalism (Gamson,

duction, the full range of social workers' political

1992).This support is commonly detailed among a

ideology was rarely examined as the central focus

multitiered ideological continuum (Brint, 1994;

of any study. No study examined multiple meaKnight, 1999; Lowi & Ginsberg, 1994; McKenna,

sures of political ideology as dependent variables.

1998). At one end of the continuum is a "radical

Therefore, the purpose of this exploratory study

left" ideology that focuses on major systemic changes

was to identify both the range and correlates of

to address oppression (Wagner, 1990)."Liberal"idesocial workers' political ideologies.

ology emphasizes government protection of individual rights (Lowi & Ginsberg) and the separation

METHOD

of church and state (Brint; McKenna). "Moderate"

The dependent variable of political ideology was

political ideology combines conservative and libprincipally measured by the 40-item Professional

eral views and favors rational, incremental change

Opinion Scale (POS) (Abbott, 1988) .The POS was

(McKenna). "Conservative" ideology emphasizes

selected as the main measure because it appeared to

the for-profit and voluntary sectors' abilities to adbe the most comprehensive and reliable scale that

dress social problems, socially traditional values, and

gauged political ideology by examining policy statesuspicion of government control (O'Connors &

ments linked to the social work profession.The POS

Sabato, 2000). Finally, at the opposite end of the

was based on NASW policy statements from 1985.

spectrum is the "radical right" political ideology,

Since that time, the positions reflected in these policy

which promotes policy relating to biblical literalstatements have not substantially changed as comism, the patriarchal family, and fiscal conservatism

pared with current NASW policy positions (per(Hyde, 1991).

sonal communication with A.Abbott, professor of

CCC Code: 1070-5309/06 $3.00 C2006 National Association of Sociai Workers

social work,West Chester University,West Chester,

PA, March 14, 2003), although clearly not all current policy positions from SocialWork Speaks (2003)

are reflected in the POS. The POS is divided into

four value dimension subscales: Respect for Basic

Rights (BRSS), Commitment to Individual Freedom (IFSS), Sense of Social Responsibility (SRSS),

and Support of Self-Determination (SDSS) (Abbott,

1988).Based on a five-point Likert scale (1 = conservative and 5 = liberal [accounting for reverse

scoring]), higher scores correspond with greater

liberalness (Abbott, 1988). Three new questions

linked to NASW policy statements ("Faith-Based

Initiatives," 2002; NASW, 2003) were added to the

POS to compensate for a few contemporary issues

not addressed and to compose a "POS+3" scale

(seeTable 1). Political ideology was measured using

a seven-point scale ranging from 1 = radical left to

7 = radical right on the self-ranked political ideology (SRPI) item (Knight, 1999). In sum, the study

comprises seven dependent variables: the POS, each

of the four POS's subscales, the POS+3, and the

SRPI item.

The study contained 15 independent variables

drawn fi-om the literature (Abbott, 1988,1999; Brint,

1994; Fisher et al., 2001;Jensen & Bergin, 1988;

Kornblum, 1997).They are personal characteristics

from analysis because they had more than 20%

missing data.Therefore, 294 surveys were analyzed,

which corresponds with a fair response rate of 52.6%

(Rubin & Babbie, 2001). Sufficient power was

achieved based on the sample size. Based on an a

posteriori analysis, using N = 138 as the lowest

number of participants in the regression models,

power of 0.80 (.7986) was achieved.

RESULTS

The sample was predominantly fetnale (85.6%),

white (80.1%), 45 years of age on average, Protestant (36.1%), and fairly strongly religious or spiritual {M = 1.96 with 1 = very strong and 4 = not

strong at all). In addition, most participants were

Democrat (78.1%) and heterosexual (93.7%) and

varied on income, with 25.5% earning between

$40,000 and $49,999 and 25.2% earning more than

$60,000. The majority of participants worked full

time (72.9%), held MSWs (83.6%), and were licensed at the LCSW-C level (59.8%). Participants

tended to work in public settings (36.6%) and in

nonprofit settings (35.5%). Finally,participants had

an average of approximately 13 years of licensed

experience and tended to work in clinical and direct social work practice (52.6%).

(gender, age, race, religion/spirituality, religiosity, sexual Range of Political Ideology

orientation, socioeconomic status), professional charac- The POS (M= 158.38, SD = 13.52) points correteristics {degree achieved as one proxy for education,

sponded with a fairly liberal political ideology; with

employment status, type of work setting, years of work

the addition of three items for the POS+3, the mean

experience, type of social work function, licensure level increased almost 10 points. Regarding the four

[created by author]), and two significant interac-

subscales, the SDSS had the highest mean (44.41,

tion effects {degree by years of [licensed] experience [r = SD = 4.00), followed by the BRSS (M = 44.07, SD

.25, p < .01] and gender by highest social work degree = 3.08), the SRSS (M= 37.38, SD = 5.18), and the

[X'(3, N = 285) = 8.69, p = .03]).

After a pilot test {N = 10) identified no major

problems, the study's sample was drawn from the

2003 membership list of the state of Maryland's

social work licensing board. Proportional random

sampling was conducted to ensure licensed social

workers from all four licensure levels (LSWA, LGSW,

LCSW, and LCSW-C) were represented. Participants received the survey, along with a cover letter,

self-addressed stamped envelope, and $1 as a token

of appreciation. A follow-up reminder postcard was

sent to all participants a week later (Dillman,2000).

Of the approximately 11,000 licensed social workers in Maryland, a sample of 558 participants was

obtained. Three hundred questionnaires were received for the data analysis, but six were removed

122

IFSS (M = 32.69, SD = 6.02) (Table 1).

The single item on SRPI (M= 3.39, SD = 0.92)

corresponds with a political ideology that is between liberal and moderate. No one political ideology was held by the majority of participants.The

largest self-ranking category was "liberal" (40.6%),

followed by "moderate" (34.4%). Slightly more than

half of participants (55.2%) ranked their political

ideology from liberal to radical left, and 10.4% indicated they were right of center (from conservative to very conservative). No one reported her or

his ideology as "radical right."

Correlates of Political Ideology

The significant correlates for each of the hierarchal regression models appear in Table 2. The best

Social Work Research VOLUME 30, NUMBER 2 JUNE 2006

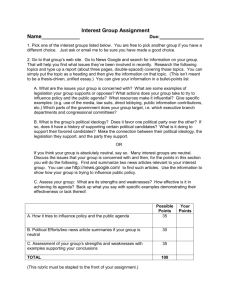

Table 1: Means and Standard Deviations of Professional

Opinion Scale + rhree Items for Social Workers

1. All direct-income benefits to welfare recipients should be in the form of cash.

2. When they are old enough, children should have the right to choose their religion, including the option

to choose none.

3. The employed should have more government assistance than the unemployed.

4. Sterilization is an acceptable method of reducing the welfare load.

5. Counseling should be available to women who ask for abortions.

6. There should be a guaranteed minimum income for everyone.

7. Couples should decide for themselves whether they want to become parents.

8. The federal government has invested too much money in the poor.

9. The government should not redistribute the wealth.

2.19

.90

4.19

3.63

4.20

.98

.91

1.05

.80

4.49

3.59

4.62

.58

4.18

.88

3.58

1.08

10. Retirement at age 65 should be mandatory.

11. Women should have the right to use abortion services.

4.37

4.34

12.

13.

14.

15.

The dying have a right to be informed of their prognoses.

The FBI (government) should keep files on individuals wirh minority political affiliation.

Abduction by parents who do not have custody should be viewed as a family, not a legal, matter.

The government should not subsidize family-planning programs.

4.80

4.22

16.

17.

18.

19.

The mandatory retirement age protects society from the incompetency of the elderly.

Welfere mothers should be discouraged from having more children.

Family planning should be available to all adolescents.

Capital punishment should not be abolished.

20. The government should provide a comprehensive system of insurance protecting against loss of income

because of disability.

1.27

4.34

4.14

4.44

.75

1.05

.50

.99

.82

2.63

.89

.(>!

1.07

4.23

3.09

1.34

.94

4.07

4.11

.80

21. Mandatory retirement based on age should be eliminated.

22. The death penalty is an important means for discouraging criminal activity.

3.68

1.20

23. Local governments should be monitored on the enforcement of civil rights statutes.

24. The aged require only minimum mental health services.

4.04

.78

4.49

.67

25. Welfare workers should keep files on those clients suspected of fraud.

2.23

4.44

.89

.70

.(>(,

.60

26. Only medical personnel should be involved in life and death treatment decisions.

27. Pregnant adolescents should be excluded from school.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

Students should be denied government funds if they participate in protest demonstrations.

Juveniles do not need to be provided with legal counsel in juvenile courts.

Corporal punishment is an important means of discipline for aggressive, acting-out adolescents.

Unemployment benefits should be extended, especially in areas hit by economic disaster.

It would be better to give welfare recipients vouchers or goods rather than cash.

4.51

4.57

4.60

.84

4.31

4.10

.64

.92

.77

2.56

1.04

3.17

34. The government should have primary responsibility for helping the community accept a returning offender. 2.81

35. Efforts should be made to increase voting among minorities.

4.20

36. "No-knock" entry, which allows the police entrance without a search warrant, encourages police to

violate the rights of individuals.

3.75

37. Family planning services should be available to individuals regardless of income.

4.60

38. Older persons should be sustained to the extent possible in their own environments.

4.43

1.10

.92

33. The gap between poverty and affluence should be reduced through measures directed at redistribution

of income.

.79

1.00

.58

.82

39. The child in adoption proceedings should be the primary client.

4.34

40. A family may be defined as two or more individuals who consider themselves a family and who assume

protective, caring obligations to one another.

4.19

.95

41. Faith-based delivery of social services is an effective method of helping people in need.

42. Special laws for the protection of lesbians' and gay men's equal rights are not necessary.

43. Social services should be provided to illegal immigrants.

2.47

3.87

3.28

1.02

RoSENWALD / Exploring the Political Diversity of Social Workers

.83

1.05

1.18

123

Table 2: Significant Variables in Multiple Regression Models

Correlated with Social Workers' Political Ideology

Variable

Professional Opinion Scale (A^= 139)

Age

Independent*

Professional Opinion Scale +3 (A'^= 138)

Age

Independent

Individual Freedom Subscale (N= 161)

.416

11.884

.366

2.816

.006

.249

2.047

.043

2.809

2.308

.006

.445

.353

14.363

.273

-2.965

.208

-.185

.394

-2.036

.044

3.348

.001

5.453

6.816

.371

.295

3.003

2.952

.003

.004

Race

Age

2.731

.160

.213

.378

2.321

3.152

.022

.002

Democrat

4.639

5.293

.384

3.134

.002

.281

2.806

.006

-.710

-1.183

-.845

-.350

-.238

-3.306

-.550

-5.639

-3.120

.001

.000

Race

Age

Democrat

Independent

.023

Social Responsibility Subscale (A^ = 163)

Independent

Self-Ranked Political Ideology {N= 180)

Other religious or spiritual affiliation''

Democrat

Independent

Work status

-.247

-.154

-2.035

.002

.044

Note: All missing variable cases were excluded listwise.

'Democrat and Independent are attributes of the political affiliation variable.

"Other religious/spiritual affiliation is an attribute of the religious or spiritual affiliation variable.

regression model was for SRPI, which explained

37.6% of the variance in political ideology and had

four significant correlates. Two of the correlates

related to political party, where participants who

affiliated with the Democratic (B = -1.183, ( =

-5.639, p < .001) and Independent political parties (B = -.845, t = -3.120,p = .002) scored approximately one point lower on the SRPI scale

than those afFiHating with the Republican Party.

Two other correlates in the SRPI model emerged

with significant findings: (1) an "other" religious

or spiritual affiliation {B = -.710, t = -3.306, p =

.001), where participants scored almost one point

lower than participants who were Protestant, and

(2) work status (B = -.350, t = -2.035, j? = .044),

with participants who worked part time in social

work scoring almost half a point higher on the

SRPI scale than those who worked full time. Finally, race and age emerged as significant correlates in the other regression equations, with participants who were white and older tending to be

more liberal than those who were not white and

124

younger. The BRSS and SDSS were not significant in their final models.

DISCUSSION

As Dinerman (2003) observed, the profession has

"grown sloppy in assuming that the prevailing beliefs of our environment are, indeed, held by all" (p.

251).To this end, it was important to examine the

political diversity of social workers, which uncovered a range of their political ideologies. Most striking from the data is that social workers' political

ideology is not a liberal monolith.

With respect to self-ranked political ideology, a

slim majority reported they were liberal or very

liberal (approximately 53% total), which counters

the stereotype of a profession dominated by liberal

political ideology. Indeed, almost as many participants reported they were moderate to very conservative in ideological thought. Having more than a

third of the sample identifying as moderate suggests that the liberal versus conservative dialogue is

too simple and perhaps based on stereotypes.Those

Social Work Research VOLUME 30, NUMBER 2 JUNE 2006

with a radical left perspective were a small percentage ofthe sample. The absence ofthe radical right

suggests that either there are no social workers who

consider themselves as radical right, at least in this

sample, or the term may be unpopular for self-ranking and used more as a label by others.

The means ofthe POS-related items suggest an

overall liberal tendency among members, although

the BRSS and SDSS subscales had higher liberal

scores than the IFSS and SRSS subscales. Upon

further review, the findings confirm Brint's (1994)

conclusion that social workers tend to be more liberal on social issues than economic issues, as the top

six liberal items (means between 4.5 and 5) related

to social welfare and four ofthe six most moderate

to conservative items related to economic welfare

(all means under 3) (Table 1). Detailing economic

welfare, for example, social workers tended to be

more liberal when welfare was needed to help with

an unexpected crisis (that is, disaster, disability) and

more moderate to conservative when advocating

for clients on welfare to have fewer children and to

record those who "commit fraud." Finally,fivecorrelates from the regression models (political party

affiliation, age, race, religious or spiritual afEliation,

and work status) support their importance in the

literature (for example, Abbott, 1988, 1999) and

suggest variables to examine in future studies.

This study's limitations require a cautious interpretation of the findings. Conceptually, using the

POS (developed to measure social workers' values)

may have limited validity when applied to measuring social workers' political ideology, because some

POS items might have more significance to political ideology than others. More conceptual development and psychometric testing of a social work

political ideology scale completely based on social

work policy statements (NASW, 2003) would be

usefiil, in addition to reconciling Abbott's (1988)

POS subscales with Brint's (1994) typology of political ideology.Although the POS and POS+3 had

good rehability (a = 0.85 and a = 0.86, respectively), the four subscales had fair reliabilities ranging from 0.65 to 0.78. The study's response rate,

approximately 53%, is a fair response rate for a mailed

questionnaire (Dillman, 2000; Rubin & Babbie,

2001), yet it does not reflect almost half of the

sample; participants who responded may be different from those who did not respond. More attention to increasing the response rate would be helpful (Dillman). Finally, because the sampling frame

ROSENWALD / Exploring the Political Divenity ofSocial Workers

was licensed social workers in Maryland, the results

of the study cannot be generalized to nonlicensed

social workers in Maryland or to any other social

workers beyond that state. National studies would

be useful.

This exploratory study's central focus on political ideology raises the volume of the barely audible conversation of political ideology in social

work. Considering its range and correlates showcases the richness of this diversity variable.The intent of this study is to help establish political diversity as a legitimate diversity variable worthy of

serious study and to add to the literature on social

work and diversity. M'l'iH

REFERENCES

Abbott.A. A. (1988). Professional chokes: Values at work.

Silver Spring, MD: National Association ofSocial

Workers.

Abbott, A. A. (1999). Measuring social work values: A

cross-cultural challenge for global practice.

International Social Work, 42, 455-470.

Brint, S. (1994). In an age of experts:The changing role of

professionals in politics and public life. Princeton, NJ:

Princeton University Press.

Dillman, D. A. (2000). Mail and Internet surveys.Ttte tailored

design method (2nd ed.). New York: John Wiley &

Sons.

Dinerman, M. (2003). Fundamentahsm and social work.

Affilia, J 5,249-253.

Epstein, I, (1969). Professionatization and social work

activism. Unpublished doctoral dissertation,

Columbia tjniversity, New York.

Faith-based initiatives discussed. (2002, November).

NASW News, pp. 1,10.

Fisher, R.,Weedman, A.,Alex, G., & Stout, K. D. (2001).

Graduate education for social change: A study of

political social workers. Jowrna/ of Community Practice,

9, 43-64.

Gamson,W.A. (1992). Talking politics. Cambridge, England:

Cambridge University Press.

Hendershot, G. E., & Grimm, J.W. (1974). Abortion

attitudes among nurses and social workers. American

fournal of Public Health, 64, 438-441.

Hodge, D. R. (2003).Value differences between social

workers and members ofthe working and middle

classes. Social Work, 48, 107-119.

Hyde, C. A. (1991). Did the New Right radicalize the women's

movement? A study of change in feminist social movement

organizations, 1977 to 1987. Unpublished doctoral

dissertation. University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Jensen,J. P., & Bergin,A. E. (1988). Mental health values

of professional therapists: A national interdisciplinary

survey. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice,

19, 290-297.

Knight, K. (1999). Liberalism and conservatism. In J. P.

Robinson, P R. Shaver, & L. S.Wrightsman (Eds.),

Measures of political attitudes (Vol. 2, pp. 59-158). San

Diego: Academic Press.

Koeske, G. F, & Crouse, M. A. (1981). Liberalismconservatism in samples of social work students and

professionals. Social Service Review, 55, 193—205.

Kornbluni,W. (1997). Sociology in a changing world (4th

ed.). Fort Worth,TX: Harcourt Brace College

Publishers.

125

Lowi,T.J., & Ginsberg, B. (1994). American government:

Freedom and power (3rd ed.). New York: W.W.

Norton.

McKenna, G. (1998). The drama of democracy: American

government and politics (3rd ed.). Boston: McGrawHill.

National Association of Social Workers. (2003). Social work

speaks: Policy statements of the National Association of

Social Workers, 2003-2006 (6th ed.). Washington,

DC: NASW Press.

O'Connors, K.,& Sabato, L.J. (IQOQ). American government: Continuity and change. New York: Longman.

Reeser, L. C , & Epstein, I. (1990). Professionalization and

activism in social work:The sixties, the eighties, and the

future. New York: Columbia University Press.

Rosenwald, M. (2004, March). Is there room for one more?

Exploring political ideologies of licensed social workers.

Paper presented at Council on Social Work

Education's Annual Conference, Anaheim, CA.

Rubin, A., & Babbie, E. (2001). Research methods for social

work (4th ed.).Belmont, CA:Wadsworth.

Rubinstein, G. (1994). Political attitudes and religiosity

levels of Israeli psychotherapy practitioners and

students. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 48, 441—

454.

Varley, B. K. (1968). Social work values: Changes in value

commitments of students from admission to MSW

graduation. JoMrna/ of Education for Social Work, 4, 6 7 85.

Wagner, D. (1990). The quest for a radical profession: Social

service careers and political ideology. Lanham, MD:

University Press of America.

Mitchell Rosenwald, PhD, is assistant professor of social

work, Binghamton University, P. O. Box 6000, Binghamton,

NY 13902; e-mail: mrosenwa@binghamton.edu.

Original manuscript received September 28, 2004

Final revision received September 29, 2005

Accepted October 28, 200S

Sqcial

Workers Do

2nd Edition I

Maigaret Gibelman I

What Social Workers

Do, 2nd Edition is a

panoramic view of the

social work profession

in action. Extensive

case studies and

vignettes highlight the

intersection between

practice functions,

practice settings, and

practice areas, connecting what appear to be

diverse specializations.

1

,

;

;

;

•

|

Written in a lucid and engaging style that is

refreshingly jargon-free, the book flows easily

from the definitions and context of the

profession to fields of practice, issues in macro

practice, and the future of the profession. It

synthesizes source materials, current research,

case studies, and insights from social work

experts in wide-ranging fields of practice,

including mental health, health care, children

and families, aging, and more.

As with the first edition. What Social Workers

Do is perhaps the most comprehensive resource

guide currently available on the social work

profession. It is a "must-have" addition to

college and high school libraries, BSW and

MSW classrooms, and the desks of social

workers at every career level. Plus, it is an

invaluable reference tool for agencies,

policymakers, legislators, and executives.

j

|

j

I ISBN: (W71O1-364-9. 2005. Item #3649. $49.99.

NASW PRESS

ORDER TODAY!

CALL: 1-800-227-3590

Refer to Code ASWD05

Visit our web site at: www.naswpress.org

to learn about other NASW Press publications.

#NASW

Ntuioaol Auocidiiod ol SocicI V

126

Social Work Research VOLUME 30, NUMBER 2 JUNE 2006