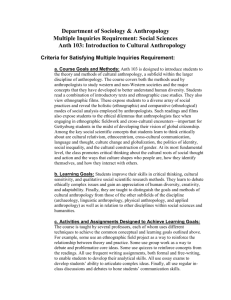

anthropology and middle class working families: a

advertisement