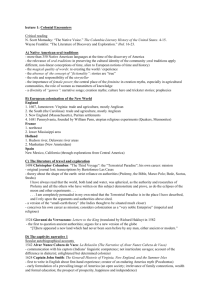

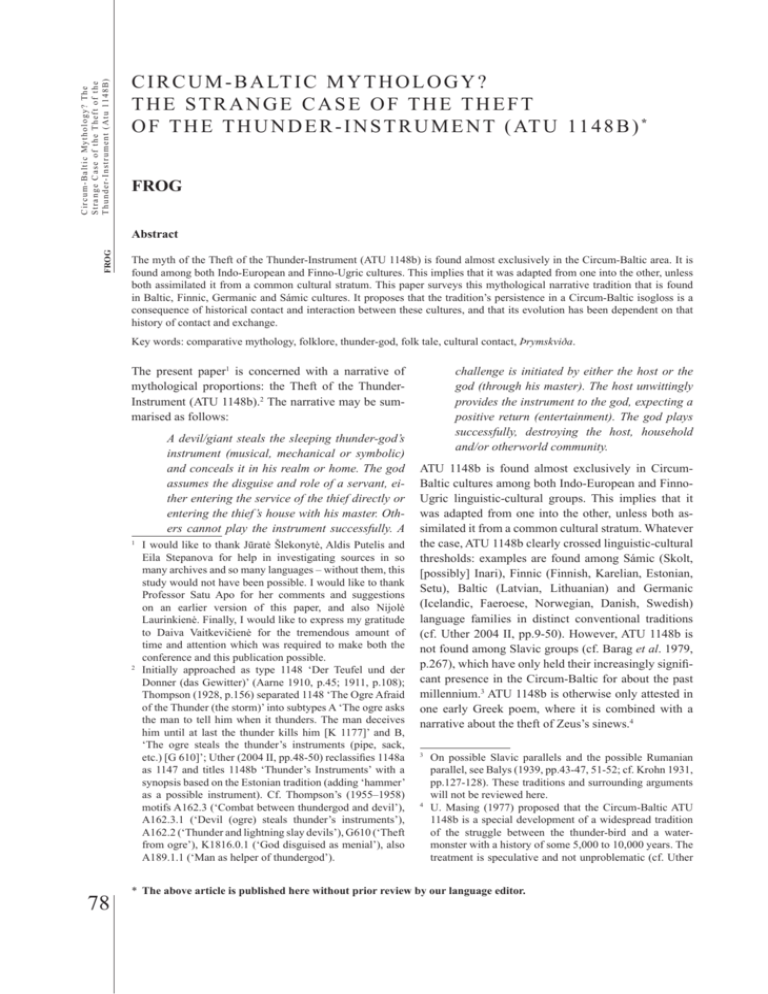

circum-baltic mythology? - Baltijos regiono istorijos ir archeologijos

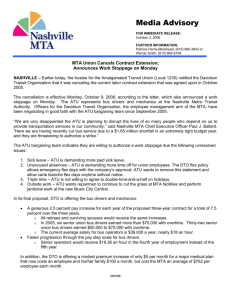

advertisement