From Indifference to Compassion: Literature, Art, and the

advertisement

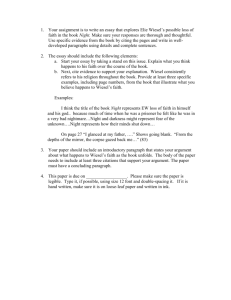

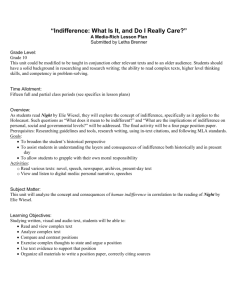

From Indifference to Compassion: Literature, Art, and the Common Human Experience Abigail Storch, sophomore 2102 Villa Dr. Greensboro, NC 27403 astorch@eastern.edu (336)404-1680 1 In his 1999 White House address, “On the Perils of Indifference,” Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel warns that it is profoundly dangerous to remain apathetic to the suffering and experiences of other human beings.1 Wiesel remarks that though it is admittedly inconvenient and troublesome to become involved in another’s pain, to refrain from doing so is inhuman - it is to deny both the humanity of the other and to betray one’s own. He goes onto explain that to be indifferent is to reduce one’s fellow human beings to creatures of no consequence, meaningless abstractions that can be easily overlooked in favor of more important matters. However, the one on whom tragedy has fallen because of others’ indifference has a certain duty to society: to speak out and tell his story. “For the survivor who chooses to testify, it is clear: his duty is to bear witness for the dead and for the living,” Wiesel declares. “He has no right to deprive future generations of a past that belongs to our collective memory. To forget would be not only dangerous but offensive; to forget the dead would be akin to killing them a second time.”2 For the sake of the human race, Wiesel exhorts the audience to listen attentively to the stories of others and to tell their own, for the very act of telling and hearing stories is the act of eradicating this perilous indifference. Art and literature serve as media for truth in a manner that disallows the public that tempting luxury of remaining uninvolved. Rather than intellectual abstractions that remain detached from imagination and emotion, art and literature demonstrate truth by inviting participation in an experience that embodies truth in tangible human terms and shows how truth plays an active role in the human life. Participation in experience through the media of art or literature integrates feeling and imagination with rational thought. In this way, art and literature 1 Elie Wiesel, “On the Perils of Indifference” (speech delivered at the White House, Washington, D.C., April 12, 1999). 2 Elie Wiesel, Preface to Night (New York: Hill and Wang, 2006), xv. 2 recognize and validate the complete personhood of the listener as a human being whose experiences are inextricably composed of sense and emotion as well as deduction and reason. The integration of the human elements of emotion and reason affirm the humanity of the reader or observer, and he finds himself involved in the experience to which he has been made privy through art or literature. In short, he has been moved to care for his fellow humans. Further, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn raises the question of the purpose of art and literature in his 1970 Nobel address. “Why this gift to us?” he queries. “How should we treat it?”3 Solzhenitsyn describes the immense power that art and literature hold as media for truth and explores the ways in which this power ought to be wielded. In the present age, it seems that art and literature are not often used to transmit experiences to illumine the truth of common ties of humanity; rather, the artist now chooses to create his own miniature cosmos in which he governs, however unintelligible the work may be to others. How might we seek, in the present culture, to regain a sense of the role of art and literature not as tools of self-expression, but as media for describing truth? Solzhenitsyn expresses this very tension in his speech and declares that in a culture where truth and goodness have been “crushed, cut down, or not permitted to grow,”4 there remains that mystery which softens the human heart and causes even the coldest of humans to care for his neighbor and to feel compassion: the mystery that is beauty. Beauty shines ever more luminous in the face of great darkness, and truth rings out most clearly in defiance of violence and lies. In art and literature, the beauty of those things common to all humans shoots through the fog of 3 Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, “Nobel Lecture,” in The Solzhenitsyn Reader, ed. Edward E. Ericson, Jr. and Daniel J. Mahoney (Wilmington: ISI Books, 2006), 514. 4 Ibid,, 515. 3 self-expression and uncertainty and reinstates the validity of truth in a manner that draws humans toward both the truth and one another. What can we do to fight indifference? We must tell the stories where truth speaks against violence, where beauty glows in the midst of suffering, where men seek and sacrifice for the good of the other. We must also bear witness to the perpetration of the horrors that humans have wrought upon one another because of hatred or neglect, and we must remain vigilant in the responsibility of moving the indifferent individual to care for the other, moving the public as a whole toward compassion, toward sight of that truth that cannot be denied in the face of an evil that threatens to overcome. Solzhenitsyn describes the true artist as one who can “sense more keenly” the depth of man’s purpose and communicate it to others.5 Through the media of art and literature, we must bear witness to this so that others may be moved from indifference toward compassion, for compassion for one’s neighbor compels him to act in the interest of the good of the other, the common good, in which his own good is found. However, our responsibility is not just to our fellow man and to the common good, but to the Truth itself. We must pay the utmost attention to the stories of others in order to escape our own indifference, the indifference that stems from ignorance. On the unique ability of art and literature to engender in a person genuine care for his fellow man, Solzhenitsyn says, “They both hold the key to a miracle: to overcome man’s ruinous habit of learning only from his own experience, so that the experience of others passes him by without profit.”6 We not only have the responsibility of telling truth and moving others to care through art and literature, but of hearing and responding to the truth as well. 5 6 Ibid., 513. Ibid., 519. 4 In his Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, Elie Wiesel declares that it is the duty of the human being to bear witness to the truth for the sake of all others. Art and literature exist because humans must know that “when their voices are stifled we shall lend them ours, that while their freedom depends on ours, the quality of our freedom depends on theirs.”7 This is the role of art and literature in today’s society: to tell, to show, to cause individuals to be moved by pain and beauty toward truth and the common good. As Solzhenitsyn poignantly muses, “Not everything can be named. Some things draw us beyond words.”8 Indeed, art and literature serve to express truth that cannot be stated in concise terms. Through inviting participation in common human experience, art and literature connect us to one another, cause us to care for one another, and compel us toward the truth that transcends our individual experiences but somehow encompasses them all. 7 8 Wiesel,120. Solzhenitsyn, 514.