STUDENT VERSUS UNIVERSITY: THE

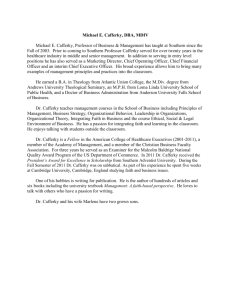

advertisement