Blue Beads as African-American Cultural Symbols

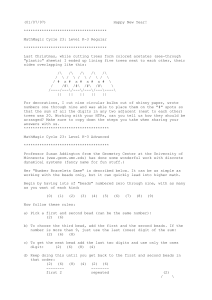

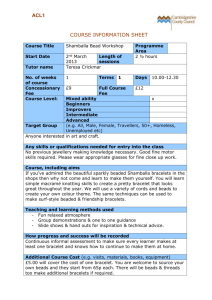

advertisement