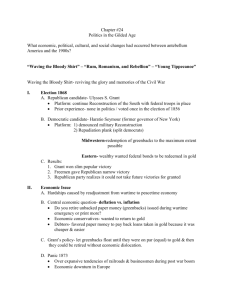

The 1920 Congressional Election:

advertisement