chapter i - Sacramento

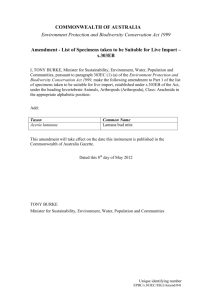

advertisement