Forms of Feminist Movement in Europe and China

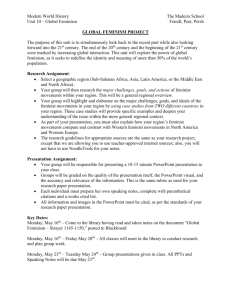

advertisement