let's go sue: the attorney general's historical

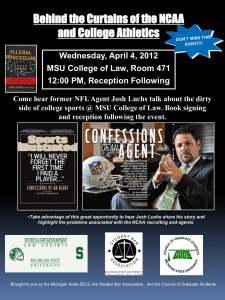

advertisement