One Is the Loneliest Number

advertisement

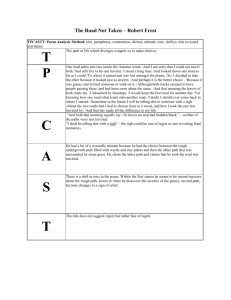

One is the Loneliest Number Rev. Rod Richards Unitarian Universalist Fellowship of San Luis Obispo County 09/27/15 The Robert Frost poem that you heard in the Reading and in the music is undoubtedly one of the most famous—if not the most famous—poem written by an American poet, or possibly by any poet. I don’t know how such things could be measured precisely, but it was the clear winner when former poet laureate Robert Pinsky asked Americans to submit their favorite poem. More persuasively perhaps, Google data makes it the most searched poem by at least four times when compared to other poets, and over twice as much when compared to popular works in other forms, such as Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone,” or F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby,” or Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho.” Further, the poem was read (without attribution) in a New Zealand Ford Motor Company commercial, as a young man mulls over the momentous decision of which car to buy, and it has been featured in a host of other commercials and advertisements in this country, including Mentos, Nicorette, AIG, Monster.com. References to the poem occur frequently in popular songs, TV shows, and it famously supplied the title of M. Scott Peck’s international self-help bestseller, selling over ten million copies, The Road Less Traveled, though I don’t believe Peck refers to the poem itself anywhere in the text (The Road Not Taken, David Orr, Kindle loc. 21-57). This is a poem that seems to be woven into our culture in ways that few poems achieve. And yet—as familiar as I imagined it was to me—I don’t think I knew it nearly as well as I thought. Now this happens: songs, poems, prayers assimilated into a culture are often reinterpreted and used in ways that may be quite a distance from—and maybe even contrary—to what the creator intended. Songwriter Carly Simon talks about how shocked she was to find that her song, “That’s the Way I’ve Always Heard It Should Be”—a stunningly bleak portrayal of marriage and family life—was being used at weddings. It’s a beautiful tune, but hearing the lyrics…it makes you wonder what these couples were thinking. “Born in the U.S.A.” by Bruce Springsteen is used at 4th of July celebrations across the country, and if you listen to the verses, you will see why that’s a puzzling thing. The Serenity Prayer is something of a misnomer as serenity shares equal billing with courage and wisdom, and if the prayer has a consistent theme throughout, it is change. “Am I my brother’s keeper?” is hardly a call to compassion when you think about it—does any human want a “keeper”?—and one need only look to the story of Cain and Abel to underscore the lurid origin of this phrase, yet it is routinely employed to remind us of our responsibilities to one another. And I understand that time and culture shape and reshape these cultural artifacts to meet the needs of the One is the Loneliest Number UUFSLOC 09/27/2015 Richards / 2 of 6 present moment and situation and that there is no law about interpretation and reinterpretation, nor should there be. (Our Board President, Jim Woolf gently pointed out that I, after all, not only misinterpreted, but misquoted Edward Everett Hale in my blurb for this service in News & Notes…so I understand how this happens). However I want to spend a little time with Frost’s poem—not because I want to lead a course in literary interpretation, a task for which I would be sadly unqualified and which might send many of you running for the exit—but because I think beneath—and along with—the culturally familiar interpretation of the poem, there are rich truths for Unitarian Universalists to consider. Unitarian Universalism, over the past half-century, has made a great shift from focusing on the individual—the inherent worth and dignity of every person—to the community, in its widest sense—the interdependent web of all existence. We are striving to balance the integrity and freedom of each person with our connection and responsibility to the whole. And so we have focused on being together. On joining in community. On being there for one another; supporting one another; calling on one another. “We would be one,” we sing together. “Take courage,” we say with Wayne Arnason in words from our hymnal (SLT #698), “for deep down there is another truth: you are not alone.” You are not alone. That is true. And…you are alone. That is also true. It does us no good to ignore this reality. Both things are true in our experience of life. Part of “nurturing spiritual growth” for me includes the ability (or, more importantly, a willingness) to hold such a paradox: You are not alone. You are alone. Comedian Lily Tomlin is quoted as saying, “We are all in this together…by ourselves,” (or “we’re all in this…alone.”) The September theme for services has been solitary—not solitary confinement, though sometimes it can feel that way—but solitary. How do we understand oneness in relation to all? How can we simultaneously feel connected and alone? How do we bridge the inevitable distance that exists between one person and another? Now a common interpretation of the Frost poem is that it is about a person who takes “the road less traveled by” and this choices makes “all the difference” in the person’s life. This corresponds nicely with much of Unitarian Universalist history and thought—Ralph Waldo Emerson writing, “Whoso would be a man, must be a nonconformist” (“Self-Reliance”) and Henry David Thoreau writing about those who One is the Loneliest Number UUFSLOC 09/27/2015 Richards / 3 of 6 step “to the beat of a different drummer” (Walden). (Appropriately enough, M. Scott Peck, who wrote The Road Less Traveled, also wrote a book entitled, The Different Drum). However, you will notice that the poem is not entitled, “The Road Less Traveled.” The poem is entitled “The Road Not Taken.” Why focus on that road? You will also notice that the poet is not saying, “I took the road less traveled by and that has made all the difference.” The poet has either just barely embarked upon the road or may even still be at the crossroads at the end of the poem. The poet is saying, Years and years from now, looking back, I will say “I took the one less traveled by, and that has made all the difference.” The poet does not know what will occur on this road and can certainly not know if it “has made all the difference.” And difference from what, one might ask. From the road not taken? And, if so, how would he know what the difference would be, because he “could not travel both, being one traveler”? And further, we’re not even entirely sure that the road less traveled by is actually less traveled, as he writes: …it was grassy and wanted wear; Though as for that the passing there Had worn them really about the same, And both that morning equally lay In leaves no step had trodden black. And I underline these ambiguities because I think--through these ambiguities--what Frost beautifully captures in this poem is that circumstance, common to all people, where we find ourselves unutterably, irretrievably alone: the point of decision. Two roads diverged in a wood. I must make a decision. No one else can make my decision, just as I can’t decide for anyone else. I must decide.. Now I can allow someone else to make the decision, but that is a decision. I can phone a friend. I can allow my life to be directed by the guidance of others—sometimes for very good reasons—but that is a decision. I can stay standing there where the roads diverge, and accept whatever consequences arise from that, or I can simply retreat, but these are all decisions. I had a little trouble with decision-making in my experience studying for the ministry. I had seminary classes and I was also doing a chaplaincy internship and I would “over-commit” by arranging an unrealistic schedule and promising to be, frankly, in two places at once so that I wouldn’t have to disappoint anyone. I was trying to avoid deciding between, or, in Frost’s world, I had convinced myself One is the Loneliest Number UUFSLOC 09/27/2015 Richards / 4 of 6 that I could take both roads at once. However, I was only one traveler, which resulted in often being late to my chaplaincy position. My chaplaincy supervisor—a compassionate, no-nonsense, firm, fair Lutheran deaconess—called me into her office one day for a review and, interestingly, called on a cultural artifact to get her point across. She inserted a CD and played me a Lovin’ Spoonful song: Did you ever have to make up your mind Pick up on one and leave the other behind It's not often easy and not often kind Did you ever have to make up your mind Did you ever have to finally decide Say yes to one and let the other one ride There's so many changes and tears you must hide Did you ever have to finally decide She made her point. Make up your mind. No one else can do that for you. A decision requires a commitment to an unforeseen and unknowable future, which inevitably feels risky. You can never do that particular decision over. Biologist Jerry Coyne, who is skeptical of the whole notion of “free will” as it is commonly understood, says, “No, we couldn’t have had that V-8, and Robert Frost couldn’t have taken the other road” (Orr, loc. 1332). Whatever you feel about free will, what is clear is that, once having neglected the opportunity to have some tangy vegetable juice or to travel a slightly more traveled road, there are no do-overs. I can now decide to enjoy a V-8 or retrace my steps to the place where the roads meet, but I cannot choose these things as the person that I was when I made the previous decision. I remember in my early days of recovery that at the root of the cravings that I would experience was not just a desire to drink, it was a desire to drink not knowing what I had come to know. It was a desire to travel back in time to a point when I was oblivious to the fact that I am a recovering addict and alcoholic. Writer, Thomas Wolfe wrote, “You can’t go home again.” He didn’t mean that you couldn’t revisit the place. He meant you could not return and be the person that you were before you left… From the Rubaiyat ofOmar Khayyám: The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ, Moves on: nor all thy Piety nor Wit Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line, Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it. One is the Loneliest Number UUFSLOC 09/27/2015 Richards / 5 of 6 And Frost captures that solitary circumstance—you will notice that no other travelers, indeed no other creatures of any kind, make an appearance in this poem— he captures that solitary situation when I have to make a decision, and I don’t know what will result from my decision, and I realize that I will never know what would have happened on the road not taken, and I can’t be sure that this is the right road, and I look and look to where each road bends into the undergrowth, and I study the ground trying to distinguish one road from the other, looking for signs that sway me one way or the other, wondering what is ahead, wondering if I somehow will be able to come back and revisit this decision, but knowing how life is and knowing how way leads onto way, knowing, too, that I will not come back and that I can never come back to this decision, and wondering then and speculating not only about which road to take but about how I will view this decision in the unseen future, how will I look back on it, how will others see it, how will I explain this decision in the years ahead, wherever it leads… That is so human! And there is a certain sense of humor that I find here, too. When we reach the last lines, it is almost as if the poet is saying, whatever happens, I am sure that I will manage to come up with a good story about it. I don’t really know what I’m doing or why I’m making this choice, but give me a few years and I’ll be singing, “I Did It My Way.” And there is something touchingly human about that, too. Writer, David Orr—whose brilliant book, The Road Not Taken: Finding America in the Poem Everyone Loves and Almost Everyone Gets Wrong inspired my reflections today—David Orr writes: We can’t accurately tell the stories of our own choices, Frost might say, but they are nonetheless ours, and there is something pleasing—or at any rate fascinating—in the way we fall short of understanding them consciously, and in the hope that we might somehow not fall short. In our reaching and failing, we create a life, a story, an art (Kindle loc. 1260). And there is some humor, too, in the circumstance. Is the decision really as important as we imagine? Will choosing this road “make all the difference”? Apparently, the poem arose from Frost’s experiences with a friend in England. Walking together in the One is the Loneliest Number UUFSLOC 09/27/2015 Richards / 6 of 6 countryside, the friend had an abnormally difficult time deciding where exactly they should go—literally deciding which road they should take--where he could show Frost the best and rarest plants, and he would inevitably berate himself afterward for having picked wrongly. “I should have remembered that they didn’t grow there…Oh, I so wanted to show you the other side of the hill…” Though it seemed important at the time, was it really so important when seen in the light of the friendship itself? Did the friend feel unnecessarily alone, caught up in trying to make a correct decision, when his friend walked right beside him? There is no doubt that I sometimes tie myself into knots of stress over which road to take, when I might pay more attention to my companions on the road I travel; when I might focus on how I am responding to the life around me, whatever road I am on. In closing, let me briefly touch upon the other poem you heard, “Invictus.” I admit to getting this one wrong, too, upon first hearing it. I thought it was the poetic version of “I Did It My Way.” “I am the master of my fate. I am the captain of my soul.” It sounded a little too Donald Trump-ish. A little too “I built this.” And then I found out a little about the life of the poet, William E. Henley. He was not writing from a triumphant position, declaring himself master of his fate. He had tuberculosis from the age of 12 leading to the amputation of one leg. He suffered health problems throughout his life, as well as other family tragedies and financial difficulties. It seems to me that what he claimed to “master” was not the circumstances of his life, but his responses to them. He continued on despite hardship. He retained hope despite disappointment. May we do our best to choose a right path, and also to make whatever path we travel right, as we recognize that we are alone together and together alone and it is compassion that connects us all. © 2015 Rod Richards