May/June 2009

Take the Plunge

Also in This Issue . . .

Throwing with Templates

Throw Really Big Pots

Is Porcelain for You?

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

1

2

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

table of contents

features

17} High Profile

22} The Pancaker

by William Schran

by Keith Phillips

Design once, throw

If you love cooking,

many. Here’s how to

here’s the perfect project

make and use throwing

for your weekend pan-

templates for great pot-

cake breakfast. Pass the

tery profiles every time.

syrup, please.

29} Getting Started with Porcelain

35} Throwing Big

by Michael Guassardo

by Antoinette Badenhorst

Throwing a large pot is

Thinking about making

simple when you do it

a switch? Meet the chal-

step-by-step. Just mea-

lenge of white clay with

sure your kiln before

a few expert tips on

you begin!

working with porcelain.

departments

6}

In the Mix

Reticulation Glazes

8}

Tools of the Trade

Green Wheels

by Robin Hopper

by Bill Jones

12} Tips from the Pros

10} Supply Room

Sun Screen

Buying Porcelain by Paul Andrew Wandless

by Antoinette Badenhorst 41} Instructors File

Throwing: A Three

Stage Approach

44} Off the Shelf

The Basics

of Throwing

by Jake Allee

by Sumi von Dassow

48} Ad Hoc

Impress your friends,

improve your life

and fill your brain.

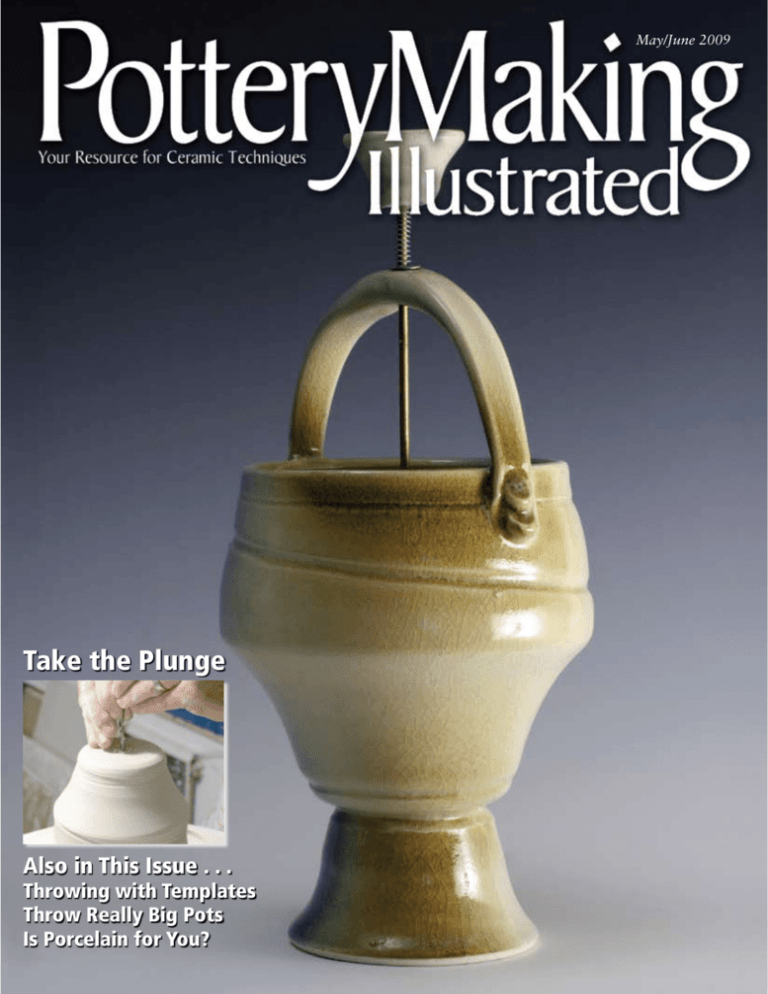

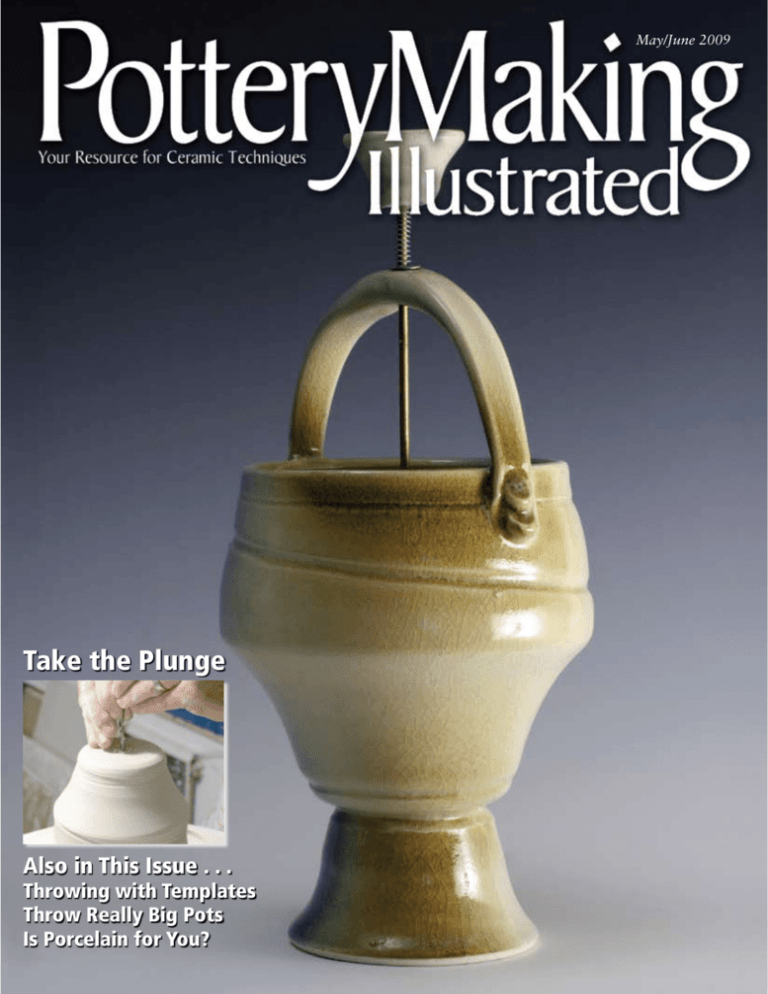

On the Cover

Keith Phillips creates

The Pancaker—the

perfect gadget for any

potter’s kitchen. See

story on page 22.

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

3

fired up

Stimulus

Volume 12 • Number 3

“You cannot depend on your eyes when

your imagination is out of focus.”

—Mark Twain

I

magination is your greatest asset in the studio, but

then that’s why you got into clay in the first place.

If you’re feeling a little out of focus because of

all the bad economic news, you’ll enjoy this “studio

stimulus package” filled with techniques, projects and ideas you can put to

use immediately.

We focused on throwing in this issue and our imaginative authors provide

a variety of perspectives. Keith Phillips’ imagination (remember the Gumball Machine in the Nov/Dec 2008 issue?) came up with the Pancaker—an

ingenious 50s-era gadget reborn as a highly creative gift idea. Keith has even

more projects in store for future issues, so stay tuned.

Do you imagine your next creation in porcelain? Antoinette Badenhorst

takes a look at what you need to know and do to be successful in this challenging medium. When she decided that she wanted her work to reflect light

and movement, she realized that porcelain was the way to go. But as she

discovered, using porcelain isn’t as simple as just changing clay—it’s a new

way of working.

We’re fortunate to have Michael Guassardo, editor of South Africa’s National Ceramics, as a contributor again. His report on the technique used by

David Schlapobersky to create large thrown vessels, which his wife, Felicity

Potter, decorates, has been missing from our repertoire of wheel techniques.

In his step-by-step description, David describes the technique for making a

large form, which he doesn’t finish. That’s where your imagination comes in.

William Schran made throwing templates so he could use the wheel to

repeat some of his favorite profiles. And while we’re on the topic of repeating things, Paul Wandless is always looking for the latest printing techniques

he can use to transfer images onto his work—take a look at his report on

screens you can develop in the sun.

And finally, there’s an ongoing argument in the throwing world about

wheel rotation. With the pottery world divided into two major traditions—

Eastern and Western—it’s no surprise there’s disagreement about which

method is superior. In our PMI Reader Survey (see p. 48), we asked a sampling of readers about what they preferred and whether they were right or

left handed. Of course the results are skewed because we’re predominantly

Western-trained potters, but what’s surprising is the number of you who use

the wheel going either direction and/or you’re ambidextrous.

Bill Jones

Editor

4

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

Publisher Charles Spahr

Editorial

Editor Bill Jones

Assistant Editor Holly Goring

Assistant Editor Jessica Knapp

editorial@potterymaking.org

Telephone: (614) 895-4213

Fax: (614) 891-8960

Graphic Design & Production Cyndy Griffith

Marketing Steve Hecker

Ceramics Arts Daily

Managing Editor Jennifer Poellot Harnetty

Webmaster Scott Freshour

Advertising

Advertising Manager Mona Thiel

Advertising Services Jan Moloney

advertising@potterymaking.org

Telephone: (614) 794-5834

Fax: (614) 891-8960

Subscriptions

Customer Service: (800) 340-6532

www.potterymaking.org

Editorial & Advertising offices

600 N. Cleveland Ave., Suite 210

Westerville, OH 43082 USA

www.potterymaking.org

Pottery Making Illustrated (ISSN 1096-830X) is published bimonthly by The American Ceramic Society, 600 N. Cleveland

Ave., Suite 210, Westerville, OH 43082. Periodical postage paid

at Westerville, Ohio, and additional mailing offices.

Opinions expressed are those of the contributors and do not

necessarily represent those of the editors or The American Ceramic Society.

Subscription rates: 6 issues (1 yr) $24.95, 12 issues (2

yr) $39.95. In Canada: 6 issues (1 yr) $30, 12 issues (2 yr) $55.

International: 6 issues (1 yr) $40, 12 issues (2 yr) US$70. All

payments must be in US$ and drawn on a U.S. bank. Allow 6-8

weeks for delivery.

Change of address: Visit www.ceramicartsdaily.org to

change your address, or call our Customer Service toll-free at

(800) 340-6532. Allow six weeks advance notice.

Back issues: When available, back issues are $6 each, plus $3

shipping/handling; $8 for expedited shipping (UPS 2-day air);

and $6 for shipping outside North America. Allow 4–6 weeks

for delivery. Call (800) 340-6532 to order.

Contributors: Writing and photographic guidelines are avail-

able on the website. Mail manuscripts and visual materials to

the editorial offices.

Photocopies: Permission to photocopy for personal or inter-

nal use beyond the limits of Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S.

Copyright Law is granted by The American Ceramic Society,

ISSN 1096-830X, provided that the appropriate fee is paid directly to Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 222 Rosewood Dr.,

Danvers, MA 01923; (978) 750-8400; www.copyright.com. Prior to photocopying items for educational classroom use, please

contact Copyright Clearance Center, Inc.

This consent does not extend to copying items for general distribution, for advertising or promotional purposes, or to republishing items in whole or in part in any work and in any format.

Please direct republication or special copying permission requests to the Ceramic Arts Publisher, The American Ceramic Society, 600 N. Cleveland Ave., Suite 210, Westerville, OH 43082.

Postmaster: Send address changes to Pottery Making Illustrated, PO Box 663, Mt. Morris, IL 61054-9664. Form 3579

requested.

ceramicartsdaily.org

Copyright © 2009 The American Ceramic Society

All rights reserved

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

5

in the mix

Reticulation Glazes

by Robin Hopper

1. LG 1 • e (10%) • 6 Ox

2. LG 1 • x (5%) • 6 Ox

3. LG 1 • x (5%) • 6 Ox

4. LG 1 • x (7.5%) • 6 Ox

5. LG 1 • x (10%) • 6 Ox

6. LG 1 • d (.625%) • 6 Ox

7. LG 1 • vg (10%) • 6 Ox

8. LG 1 • e (2.5%) • 6 Ox

9. LG 1 • x (5%) • 6 Ox

10. LG 1 • u (7.5%) • 6 Ox

11. LG 1 • h (.625%) • 6 Ox

12. LG 1 • h (7.5%) • 6 Ox

13. LG 2 • b (.625%) • 6 Ox

14. LG 2 • b (1.25%) • 6 Ox

15. LG 2 • h (5 %) • 6 Ox

16. LG 1 • base • 9 R

17. LG 2 • x (10%) • 9 R

18. LG 1 • x (10%) • 9 R

19. LG 2 • c (5%) • 9 R

20. LG 2 • u (10%) • 9 R

6

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

R

eticulation glazes form a group

of specialized glazes that show

patterns of heavy crawling, or

reticulation. The patterns look similar

to lichens, lizard skin and leopard skin,

depending on the glaze base, underglaze coatings and firing temperature.

The same glaze may give very different

results at a variety of temperatures.

Putting the reticulation glazes over

a colored slip allows the top glaze

to move and the visible cracks to be

colored between “islands” of glaze. Any

colored slip will do, but one of the most

interesting is usually black, as it intensifies the color of the covering glaze.

With reticulation glazes applied

heavily over the slip and fired at cones

04, 6 and 9-10, and with added colorants, a wide range of textural possibilities can be developed. The main

requirement in the glaze is a big saturation of magnesium carbonate as seen

in the two typical base glazes below.

Hopper LG #1

Soda Feldspar . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27%

Magnesium carbonate . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Ferro frit 3134 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Ferro frit 3195 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Talc . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Zinc oxide . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Kaolin . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

100 %

Hopper LG #2

Soda Feldspar . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35%

Magnesium carbonate . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Ferro frit 3195 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Talc . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

Kaolin . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 15

100 %

Excerpted from The Ceramic Spectrum by

Robin Hopper. For more information, visit

www.ceramicartsdaily.org/books.

Soldner Clay Mixers

by Muddy Elbow

Manufacturing

310 W. 4th

Newton, KS • 67114

Phone/Fax (316) 281-9132

conrad@southwind.net

soldnerequipment.com

Key for Colorant Additions

b = cobalt carbonate

c = copper carbonate

d = manganese dioxide

e = nickel carbonate

h = chromium oxide

u = Commercial Yellow Stain

vg = Commercial Victoria Stain

x = Cerdec/Degussa inclusion red stain 27496

Key for Firing

6 Ox = cone 6 oxidation

9 R = cone 9 reduction

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

7

tools of the trade

Going Green

by Bill Jones

E

xisting in one form or another for more than

10,000 years, the potter’s wheel has evolved

slowly over the millennia. In the 21st century,

electric wheels with enhancements reign supreme, but

the venerable, traditional kick wheel still hangs on—a

testimony to its simplicity.

There are basically two types of foot-powered

wheels—kick wheels and treadle wheels. The kick

wheel utilizes a heavy flywheel that stores energy as

it speeds up when propelled by your foot, while the

treadle wheel utilizes a lever and cam mechanism that

turns a shaft with a weighted flywheel. Operating a

foot-powered wheel takes a little practice and coordination, but potters who use them swear by the relaxed

rhythm and pace of their throwing as well as their

intimate connection to the throwing process.

Kick Wheels

There are three major manufacturers of kick wheels

in North America: Thomas Stuart wheels made by

Skutt, Brent wheels made by Amaco, and Lockerbie

wheels made by Laguna Clay. Most basic kick wheels

are constructed with a steel frame and come with an

adjustable seat, reinforced cast concrete flywheel,

cast metal wheel head and wood or composite work

surface. Some accessories are also available. And even

though you can power the wheels by foot, some models come with an electric motor option. With flywheels

Western kick wheels typically feature a steel frame with a

reinforced cast concrete flywheel, cast metal wheel head,

adjustable seat and wood or composite work surface.

Once a flywheel is rotating, the weight of it (between 120

and 140 pounds) provides momentum. An electric motor

can maintain the momentum of a moving flywheel.

Pictured: Brent J Kick Wheel

Pictured: Skutt Thomas Stuart Kick Wheel with optional motor

Since the designs of most wheels have been around for

up to 40 years, parts are easy to come by. For example, Laguna’s Lockerbie wheels can be retrofitted with a motor.

For the economy minded, a knock-down wooden Brent

wheel comes in a kit with all hardware. The flywheel is

weighted with bricks sandwiched between two plywood

pieces. Pictured: Brent Kick Wheel Wood Kit

Pictured: Laguna Clay’s Lockerbie Wheel

8

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

much remains in one place due to

its weight. Since they are bulky and

heavy, consider having your wheel

shipped unassembled to save on

shipping. For the budget conscious,

the Brent Kick Wheel Wood Kit is

economically priced. And if you’re

really industrious, you can search

for “kick wheel plans” online and

construct your own or give a set

of plans to a local woodworker to

have one custom made. n

Who to Contact

These manufacturers have detailed

information on their websites along

with information on their distributors.

Brent Kick Wheels:

www.amaco.com

Thomas Stuart Kick Wheels:

www.skutt.com

Lockerbie and Laguna Kick Wheels:

www.lagunaclay.com

Great River Woodworking Leach

Treadle Wheel:

http://greatriverwoodworking.com

This Leach Treadle Wheel, crafted by

Great River Woodworking, is based

on a style attributed to Bernard Leach

at the onset of the 20th century.

Typically made to order, these highly

prized wheels remain a favorite of

many working potters.

Photo courtesy Great River Woodworking

weighing more than 125 pounds,

the motors easily maintain momentum after the flywheel is turning.

Treadle Wheels

Treadle wheels, which rely on a

foot-powered treadle mechanism

to drive a flywheel, were once

common in English and American

potteries and more recently mass

produced for both school and

private studio. The most common

version now available is a sit down

version based on a designed refined

by Bernard Leach at the beginning

of the 20th century. The so-called

Leach wheel is legendary among

potters who prefer the non-electric

wheel, probably because of the

comfort achieved even throwing for

long stretches of time.

Buying Considerations

In the age of electric wheels,

kick wheels are a throwback to

a simpler time. And while many

consider it easier to learn the basics

of throwing on an electric, there

remain many potters who rely

solely on a kick wheel for all their

production needs. Maintenancewise very little is needed, however,

once installed, a kick wheel pretty

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

9

supply room

Buying Porcelain

by Antoinette Badenhorst

I

f you’ve only worked with red, brown or buff clay in

the past and you’re looking for a change, maybe porcelain is the right clay for you. Planning, research and

evaluation are the best ways to assure any future success

in making a switch from one clay body to another.

To determine if porcelain what you’re looking for,

you’ll need to evaluate where you want to go with your

clay work, your skill level and your vision as a potter.

Decide if you’re happy with your current work, and if

so, consider the effect that work will have if made with

a white or porcelain clay body. Not all works in clay

maximize the qualities that porcelain has to offer, so if

you have to change your work in order to use porcelain,

evaluate whether that’s something you want to do.

In my own experience, I had a vision of pots dancing

like ballerinas—soft figurines moving around in bright

colors against pure white backdrops. I also envisioned

translucent light and instantly knew what to do, but it

took some time to find the right porcelain and to develop

a body of work.

Studio Setup and Working Methods

Do you have the right studio setup for porcelain and

are you able to adjust your current workplace with

ease? Can you work with precision and in a clean

studio? Do you work with other clay bodies that might

contaminate porcelain, or are there other potters

working with you that might not respect a porcelain

work station? Which techniques do you use most? For

instance, if you work mostly with an extruder with a

steel chamber and plunger, you’ll need to replace it

with a stainless steel or aluminum one to avoid possible rust contamination.

Different Porcelains

If you want to become a porcelain production potter,

you’ll look at a different clay body than someone who

wants to make one-of-a-kind porcelain pieces, porcelain

sculptures or strictly hand-built forms. Your working

methods will differ dramatically from theirs. Maybe you

need a clay body that combines some or all of the above

mentioned clay techniques.

Once you decide that you want to take on the challenges that porcelain offer, you’ll have to find the clay

that suits your newly set goals. There are many different

porcelain clay bodies available on the market.

I tested several commercially available cone 6 porcelain

bodies and suggest you do the same before settling on

one. Each clay had some special characteristic that I could

use for my own work and could see used by anyone else.

Commercial porcelain clay bodies meet almost all the

needs of the potter, and there are some excellent throwing,

handbuilding and sculpture bodies available. The producers and suppliers know which one best suits each purpose,

and they are an excellent resource when you are trying to

figure out what you need.

Skill Level

It’s important to know your own abilities and skill level.

If you’re a beginner who wants to throw 20 inch pots,

you’ll have a lot of difficulty achieving your goals and

there will be a whole lot of frustration, time and money

wasted before you can reach them. In such a case, it’s

better to use white stoneware clay and gradually work

your way first through a semi-porcelain body and then

eventually use pure porcelain as your skills improve.

10

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

Before making a large investment in porcelain, test several

bodies to see which one best suits your needs.

They develop some bodies to be

more plastic and stretchable, but less

white and translucent. These bodies

can go further in height and thinner

in walls than some others that might

be pure white and translucent, but

may be a little harder to throw.

If you choose to work with pure

white, translucent clay, you can

always throw thicker and trim thin

afterward. If you need an all translucent, white and a non-warping

clay body, it might cost a little

more, but your ceramic supplier

can recommend the right clay body

for your purposes.

Amazingly, you will even find

that some of the semi-porcelaneous

clay bodies meet all the characteristics of porcelain and have the

added green strength that is often

missing in true porcelains. Add

these qualities to the fact that you

can save energy because many of

the commercial clays are formulated for firing at cone 6 electric, and

there are very few restrictions left

that would limit you from working

with this material.

Test several clay bodies for

their ability to throw, to trim and

to keep their shape even when

stretched to their limits. Also test

them to see how they stand up to

adjustments and attachments, then

fired them to the proper cone in an

electric kiln. I checked them to see

if shrinkage can cause problems.

Compare the tests for shrinkage,

color and translucency.

A Final Word

I’ve seen porcelain clay bodies

improve from one batch to another.

Clay companies are constantly doing research to improve their clays.

If you consult your clay company,

they’ll know what to recommend

to you only if you understand your

own needs and what you want. To

us, as potters, that’s good news,

because it means that if we admire

a specific clay body today, but it’s

not working for our circumstances,

it’s worth discussing that with our

clay producer and retesting a body

again to see if it has changed. Maybe

your skills improve, perhaps the clay

composition improves, or maybe you

and that specific clay body simply get

in sync with each other.

Read the literature available online, then talk to a sales representative and they’ll be able to recommend

the right clay body for your needs. n

Thanks to T Robert at Laguna Clay and

Carla Flati of Standard Ceramics.

Transition Carefully

It’s always best to start by buying one bag of clay and testing it

thoroughly. Then, even when you

think you’re satisfied with your

choice, make the transition to your

new style and clay body slowly and

carefully. Porcelain is expensive but

if you take a conservative approach,

and do enough testing to make an

informed decision, it will pay to

make an investment in a large batch

of clay.

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

11

tips from the pros

Sun Screen

by Paul Andrew Wandless

S

creenprinting ranks as one of the most popular

printmaking techniques because it can be used to

apply images to virtually any surface.

Clay artists are always looking for simple options to

transfer complex images, designs, patterns, digital images and photography onto their ceramic pieces. While

many image transfer techniques, such as decals, require

chemicals and equipment, I’ve discovered a simple, commercially available screen that requires minimal effort

to create an image for printing. The product is called

PhotoEZ (available at www.ezscreenprint.com) and it’s

designed for use with simple black and white photocopies and the sun. You can go from an idea to screening an

image on clay in about an hour! How cool is that?

Overview

PhotoEZ is a screen that’s pre-coated with a lightsensitive, water-soluble polymer. Instead of using a

light table to expose an image into the emulsion, you

simply use the sun as your light source to expose the

Image on a Hi-Res screen by Chicago artist Tom Lucas, used to print on clay.

12

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

screen for about 5 minutes then soak (develop) the

screen in tap water for about 15 minutes. After the

exposed areas have been hardened or “set” during the

soaking, rinse the screen with water to wash away the

unexposed emulsion and create an open, stencil version of your image.

The final step is putting it back in the sun for another 15

to 20 minutes to harden the emulsion and make the screen

more durable. Experiment with the test strips included in

the kit to get the hang of exposing and setting the screen

before using a full sheet for your final image.

Image, Paper and Screen

For best results, the type of image, screen mesh size and

photocopy paper must be suitable and compatible with

each other.

Though your image can be simple or complex, it must

be black and white. It can be line art, an illustration,

photograph, digital image or halftone. Line-art images

have few, if any, small details and consist more of bold

lines and shapes or silhouettes with high contrast and no

mid tones, so those are considered simple images. Illustrations, photographs, digital images or halftone images that

typically have finer lines and smaller details are considered

complex images. (Note: If the line or image parts are too

fine or small, the screen will clog when printing.) Once

you choose an image, make a black and white print or

photocopy using paper that is no more than 20-pound

weight and has a brightness rating of 84 or less.

PhotoEZ screens come in two mesh sizes for simple

or complex images. The Standard screen is 110 mesh

and the Hi-Res screen is 200 mesh. The 110 mesh has

larger openings and is best for simple images, while

the 200 mesh is a tighter screen (with more threads

per square inch, resulting in smaller openings) and is

best for the more complex images. Both screen meshes

come in a variety of sizes.

The image in figure 1 started with digital photographs of tools in my studio, which were altered in

Photoshop to make them high contrast black and

white images. As shown here, you can arrange the images on the screen in a group, leaving half-inch spaces

between individual images for easier printing. You

can also choose to fill the screen with just one image,

a pattern, motif, text or any combination of these.

Whatever you want to use visually on the surface of

your work is fair game. I printed on a 8½×11 in. sheet

of paper using an HP laser printer.

Setting up the Exposure Frame

With the black and white image on paper, you’re

ready to set up the exposure frame. Everything needed

is supplied in the PhotoEZ Starter Kit—one 10×12 in.

exposure frame (black felt-covered board with clips

and Plexiglas), two sheets of 8½×11 in. Standard Pho-

1

Peeling protective covering off the screen.

2

Left to right: Black felt covered board, screen centered

over photocopy placed on Plexiglas and fastening clips.

toEZ screens (110 mesh), small test strips, one plastic

canvas and a small squeegee. Tip: Be sure to work in a

dimly lit room while setting up the exposure frame to

avoid prematurely exposing the screen.

Remove the protective covering from both sides of

the Plexiglas and place it on a flat surface, then align

your black and white image in the center. Take one of

the PhotoEZ screens from the protective black envelope then close the bag tightly so the unused screen

inside is still protected. Peel the protective backing off

the screen (figure 1) and immediately place it shiny

side down on top of the black and white image (figure

2). Place the exposure board on top of the screen with

the black felt side down and clamp together with the

clips provided in the kit.

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

13

As soon as you’re done, take the frame out into the

sunlight. Keep the Plexiglas side down to keep light

from hitting it or cover it with a towel to protect it

from light before and after exposing it to sunlight.

Exposing and Setting the Screen

Once outside, turn the exposing frame Plexiglas side

up to face the sun. Expose for 5 minutes during a

regular sunny day and for 6 minutes if it’s a slightly

overcast day. Dark, cloudy days with no real sunlight

are not optimal and success varies if exposed under

these conditions. I exposed this screen for 6 minutes

on a partially cloudy day, but had good sunlight

through the light clouds.

Once exposure is complete, turn the frame over

(Plexiglas side down) or cover with a towel and go

inside to “set” the screen in a dimly lit room. Unclamp the frame and submerge the screen in a sink or

3

Using the Screen

Rinsing screen to remove unexposed emulsion.

4

Dabbing off extra water from screen.

14

container filled with cool water for a minimum of 15

minutes to develop your stencil. Soaking longer than

15 minutes doesn’t harm the stencil in any way. After

a minute or two, the unexposed areas blocked by the

dark parts of your image appear light green. The exposed areas turn dark, and these darker areas become

the stencil in the next step.

After 15 minutes, place the perforated plastic canvas

provided in the kit under the screen and rinse with

cool water from a faucet or kitchen sprayer (figure 3).

The plastic canvas acts as a protective backing for the

screen during the rinsing process. Rinse both sides of

the screen to remove the unexposed emulsion (light

green areas). Take more care when rinsing the side

that the emulsion is applied to. Keep rinsing until all

the residue from the unexposed emulsion is completely

removed. Use a soft nylon brush if there are some

small detail areas that did not rinse out very well. This

will happen more with complex images in the Hi-Res

screens because of the tighter mesh screen.

When you think you’re done rinsing the screen, hold it

up to the light to check it. You should only see the white

threads of the screen itself in the open areas. If you still

see a thin film of residue, rinse again until it’s removed.

Once open areas are completely rinsed, place the screen

emulsion side up on a dry paper towel and dab off all the

excess water (figure 4). Put a fresh dry paper towel under

the screen with emulsion side up and take it outside to

re-expose in the sun for 10–20 minutes. This hardens the

stencil and makes it more durable and longer lasting.

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

Once the screen is hardened, you’re ready to start using

it! Since the screen is unframed, it’s flexible and can

be used around a vessel or on a flat slab. Any surface

you can bend the screen around is fair game to print

your image on. Be careful not to make creases in the

screen if you try to bend it around sharp corners. This

will keep it from lying flat if you want to print on a

flat surface in the future. If you group them onto one

screen, you can also use scissors to cut it into smaller

individual images.

Experiment and have fun with this easy to use product. It’s a great way to create images for screenprinting on clay that you thought were only possible with a

darkroom. You can screen images directly onto greenware, bisqueware or decal paper using both underglaze

and glaze. Please feel free to e-mail me about your

experiments and experiences. n

Paul Andrew Wandless is a studio artist, workshop presenter,

visiting assistant professor and on the Potters Council Board of

Directors. He authored a book titled Image Transfer On Clay

(Lark Books). His website is www.studio3artcompany.com and

he can be e-mailed at paul@studio3artcompany.com.

Potters Council 2010

Exhibition FILL-adelphia

CALL For ENtrIES:

Deadline to SubmIt is July 1, 2009

First juried exhibition of Potters Council members’ work

to be held in conjunction with NCECA 2010 in Philadelphia, PA.

Entrants must be members of the Potters Council both at the time

of application and at the time of the exhibition.

Public reception on April 2, 2010 at A Show of Hands Gallery.

Go here for submission form

www.potterscouncil.org

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

15

A Texas potter makes 1,300

pound quilts with her Paragon

Dragon

As a child, Earline Green made hand-stitched quilts with

her grandmother Mama Freddie. Earline spent more time

quilting with the older ladies than she did playing with children her own age. Her early experiences with the lively quilters

taught her a life-long love of artwork.

Earline’s other grandmother, Mama Ginger, taught her

advanced quilting patterns. Later this influenced the design of

Earline’s stoneware quilt tile mosaics displayed in the entrance of the Paul Laurence Dunbar Lancaster-Kiest Library

in Dallas, Texas. For that project, Earline fired 284 white

stoneware tiles—all in her faithful Paragon Dragon.

“The Dragon's design and controls are perfect for firing

large flat pieces,” said Earline. “The digital programming controls provide a consistent firing environment that eliminated

cracks and warpage in this project.

Earline Green’s

clay spirit quilts

on display in

the Dunbar

Lancaster-Kiest

Branch Library

in Dallas,

Texas.

16

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

Earline Green with her Paragon Dragon front-loading kiln. This kiln is becoming a favorite with potters. It is easy to load, heavily insulated, and designed to reach cone 10 with power to spare.

“During tile production, I fired my Dragon two or three

times a week for four to six weeks at a time. I expected and received excellent results with each firing.”

Contact us today for more information on the exciting

Dragon kiln. Ask about the new easy-open switch box hinged

at the bottom. Call us for the name of your local Paragon distributor.

Better

Designed

Kilns

2011 South Town East Blvd.,

Mesquite, Texas 75149-1122

800-876-4328 / 972-288-7557

Toll Free Fax 888-222-6450

www.paragonweb.com

info@paragonweb.com

High Profile

Throwing with Templates

w

by William Schran

hen my beginning

wheel-throwing students have developed

sufficient facility with

clay, they’re assigned the project of

creating a set of four matching cups.

Though I’ve demonstrated how to

measure their forms using calipers

and other devices, I continue to observe them experiencing difficulties.

In an effort to overcome this stumbling block, I showed them a technique successfully used by students

in a beginning handbuilding class.

Some of the shapes used to create design templates.

This technique involves using

templates to repeatedly create an

even, symmetrical form. In the coilbuilding exercise, you position the

template next to the pot as coils are

added, making certain the pot conforms to the profile of the template.

The template is then used as a rib

to scrape the surface as it's rotated,

creating a smooth, uniform surface.

Making a Template

Any number of objects can be employed to design templates that have

a variety of shapes. French and ships

curves, found in drafting or mechanical drawing sets, are excellent tools

for creating profiles for wheel-thrown

vessels. A variety of calipers can be

taken apart to create any number

curved forms. Lids of various sizes

can be combined to create a mixture

of curves. This process can also be

used to produce templates with more

complicated and compound profiles

with relative ease.

Assortment of bottle forms made with templates.

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

17

Templates used to throw cups.

Template shapes used to throw bottle forms.

To incorporate this technique into wheel-throwing, I

began testing various materials that might serve the function of a template. Sheet plastic, a durable material that

can easily be cut and shaped, turned out to be the best

material. Searching through scraps available at local glass

supply and repair shops, I found pieces of ¼ in. and 3/16 in.

sheets that could be readily shaped into the desired profiles by cutting them with a power saw and handsaw. The

edges can then be smoothed with fine sandpaper.

the top to the bottom, pushing out where necessary, to

conform to the profile of the template. This is often necessary for shapes with wider diameters. Refine the rim

with a sponge or chamois and the cup is complete.

Creating the Form

To use a template, as in the wheel-throwing project for

the set of cups, prepare several balls of clay weighing

between ¾–1 lb. each. Throw a basic wide cylinder.

Check the interior diameter, height and width of this

basic form with calipers.

Tip: Make a template for the basic cylinder form as well

as the finished piece. The first template, showing the

right width and shape of the ideal starting cylinder, can

help you get the right basic shape.

Once you have your cylinder ready, lubricate the interior of the pot, but do not lubricate the outside. Avoiding excess water results in a stronger form that can better withstand manipulation and alteration when using

the template. Position the bottom of the template so

that it’s just touching the bottom of the pot and rests on

the wheel head. The template should contact the wheel

but should not be pressed against it. Hold the template

at approximately a 45° angle, abutting the rotating

clay, such that the clay moves away from the edge of

the template. The template should not be held at a 90°

angle to the pot as this may lead to inadvertently shifting the template into the movement of the clay.

The fingers of the interior hand slowly move up, pushing the clay out to the curve of the template. As the pot

widens, the hand must move up along the interior of the

form more slowly so that it remains symmetrical. After

reaching the top, the profile of the pot and template

should be compared. If the pot does not match the template, move the fingers of the interior hand down from

18

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

Large or Complex Forms

Templates are also useful in creating larger pots, particularly bottle shapes. This provides a method to quickly

create multiples of the same form, but also the opportunity to explore changes to certain areas, such as the

neck and rim. The process of working with larger forms

follows the same steps as you would for cups, except

the neck and rim are made without the template.

Make another cylindrical shaped pot, leaving the top

portions of the wall, including the rim, thicker than

the rest of the pot. Position the template and push the

clay out to conform to the shape, moving fingers on

the interior up and down as necessary. After creating

the desired curve, pull up the upper portion of the wall

to thin it out and narrow it in using a collaring movement. Note: It is very important to continue moving

your hands up while collaring in to maintain a curve or

arch in the shape of the wall. A wall that becomes too

horizontal or flat may collapse. In order to collar in the

pot, Using the middle fingers and thumbs to constrict

the neck, As you create the neck, pressing down on the

rim with the first finger of the right hand helps to maintain a level top.

Use a flexible rib after each collaring process to refine

the shape and maintain the desired curve. Using the rib

also removes excess water and compresses the clay. After narrowing the diameter of the pot, the wall has been

thickened and can now be pulled up thinner. As the top

becomes too narrow to insert a sponge to remove lubricating water from the interior, switch to using slurry to

lubricate the clay instead. This allows your fingers and

tools to continue shaping the clay without building up

excess torque that might twist or tear the clay wall. Using slurry on the exterior, instead of water, provides a

stronger clay wall. n

1

Template held against basic cylindrical form.

3

Hold template at an angle against surface during forming.

5

The interior hand slowly moves up, pushing the clay

against the template.

2

Pushing clay out to the template.

4

Larger forms also begin with a basic cylinder form.

6

The interior hand moves from the top to the bottom, making certain the pot conforms to the template.

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

19

8

7

Collaring the neck. The middle fingers confine the shape,

thumbs push in, first finger of right hand presses down on

the rim keeping it level.

A flexible rib removes water and slurry while compressing

and refining the wall.

10

9

When the top becomes narrower, use slurry rather than

water to lubricate the interior of the pot.

Use slurry to lubricate the exterior to maintain a stronger

clay wall.

Set of cups made with a template, shino and turquoise

glazes, fired to cone 10.

Set of cups made with a template, iron matte glaze, fired

to cone 10.

William Schran is Assistant Dean of Fine Arts at Northern Virginia Community College, Alexandria Campus. Visit his website,

www.creativecreekartisans.com, for more information.

20

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

21

The

*

*

Pancaker

*

*

by Keith Phillips

e

ight years ago, shortly after our son was born, ally have a great selection. A spring from a retractable pen

my mother-in-law was visiting and stayed with might work in a pinch. Finally, the #6–32 die probably has

us through Christmas. My brother lived near us to be purchased as part of a tap and die set. This will be

at the time, and gave my mother-in-law a vintage used to thread the rod once you have it measured and cut

pancaker from the 50’s. You filled it with batter, held it over to size.

a hot skillet and depressed the plunger for a few seconds

to open the plug at the bottom and let the batter flow into

the skillet. The result: perfect pancakes with no mess. The Start by throwing a tall bowl with 2½–3 lbs. of clay. The

pancaker she received came in the original 1950’s box— shape or style is up to you (it doesn’t have to be round!).

everything about it was cool. I probably made pancakes Be sure the rim is a little thicker than normal. The weight

every day during her visit.

of the basket-type handle can spread the bowl during firA few years ago, I was pondering what handmade item I ing, and a sturdy rim helps counter that.

would give my brother for ChristThough the overall shape is

mas and decided on the perfect

up to you, the bottom of the

“re-gift”­—I’d try to make my own

pot should be about ¼–3/8 in.

pancaker out of clay. After a few

thick. The plug will be cut out

3–4 pounds of clay

attempts, I settled on the following

of the bottom later and making

2 ft. of 1/8 in. brass or stainless steel rod

design. As with any other work, I

it a little thicker makes this plug

7/32 x 1¾ in. 020 compression spring

always like to make sure the destronger. I usually taper the botsign is flexible enough to make a

tom of the form in slightly (fig2 #6–32 hex nuts

variety of forms that will still fit

ure 1), making a graceful transi2 #8 washers

the function.

tion to the pedestal foot that’s

5-minute

epoxy

My pancaker is basically a tall

attached later.

#6–32 die (available at home centers)

basket or bowl that has a pedesNext, throw the pedestal. This

tal attached to the bottom to keep

needs to be a bottomless form.

the stopper from touching the

It is thrown upside down, with

counter. The plunger rod and nuts ideally should be made the bottom tapered to match the diameter of the botfrom stainless steel, however this is usually hard to come tom of the bowl (figure 2).

by, so a brass rod works just as well. The right-sized spring

Finally, throw a little knob. I find it easier to throw

may also be hard to come by, but farm supply stores usu- small items off the hump, since the form I’m throwing

Throwing the sections

Materials

22

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

This 111/2 inch high porcelain pancaker is basically a tall basket or bowl with a pedestal attached to the bottom to keep

the stopper from touching the countertop. Beyond that basic requirement, the form is open for your creative touch.

is raised up on a mound of clay rather than close to the

wheelhead, I can easily get to the underside and shape

it (figure 3). When you’re finished, just slice it off the

mound using a wire tool.

Trim the bottom of the bowl. You don’t need a proper

foot since it will sit on the pedestal. Before taking it off the

wheel, cut out the plug from the bottom. First take a ¼

in. drill bit and drill a hole in the exact middle of the bowl

(figure 4). Then take your needle tool and cut a 1¼ inch

diameter circle out of the bottom. This piece becomes the

plug, so take care when cutting it out to keep it intact. Hold

the needle tool at an angle and not straight up and down

when making this cut. This creates an inward taper on the

plug, so that it can easily be pushed open, but makes a seal

when closed (figure 5).

It will be impossible to make the pancaker water tight,

but batter is thicker and won’t seep out. Just make sure the

plug matches the hole as closely as possible.

Joining the parts

Now score and slip the pedestal and the bottom of the

bowl, then attach the two together (figure 6).

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

23

The Pancaker!*

2

1

Using 2½ to 3 lbs. of clay, throw the

body of the pancaker, making it taper

in slightly at the bottom.

8

7

Attach a small flattened coil to the

inside bottom of the bowl as a second

guide for the plunger rod.

Slide the other end of the rod into the

bottom opening, through the bottom

guide and into the handle.

PotteryMaking Illustrated

Drill a hole in the second guide. Flip

the pancaker over and re-insert the

plug to make sure the holes line up.

14

13

24

Throw the pedestal separately as an

open form, thrown upside down.

|

Pull the rod up and check that the

plug fits securely into the opening.

Set the pancaker aside.

May/June 2009

3

Throw a little knob off the hump so

you can get under it and shape it.

9

Attach a handle then drill a hole

through the center when leatherhard. Check that the holes line up.

15

After inserting a scrap piece of rod and

a spring into the knob, make a mark

on the rod where the spring ends.

* some assembly required

4

Trim the bowl section then use a drill

bit to create a hole in the exact center

of the bottom of the bowl.

10

Drill a ½ in. deep hole in the knob using a ¼ in. drill bit.

16

Moving up from the handle, mark this

measurement, (minus ½ in.) onto the

rod in the pancaker, then cut to size.

6

5

Using a needle tool held at an angle

to create an inward taper, cut a 1¼ in.

circle to make the plug.

11

After threading the die onto the rod,

unscrew it carefully to reveal the

threaded end.

17

Disassemble. Epoxy the rod into the

knob, slide on a washer below the

spring, and insert into the handle.

Score the surfaces of the pedestal

foot and the bowl, apply slip and join

the two parts together.

12

Slide on the fired clay plug, a protective washer, and then thread on a nut

to secure the plug.

18

Slide the rod down through the second guide, flip the pancaker over and

reassemble the stopper mechanism.

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

25

*

*

*

Press Plunger – then release

for perfect pancakes!

Roll out a small coil about an inch thick and then gently

flatten it so it gets a little wider, while keeping it about a halfinch thick. Form it into a bridge, then slip and attach it to

the inside bottom of the bowl so that it spans the hole. This

is a second guide for the plunger rod, and will help make the

stopper line up and the plunger operate smoothly (figure 7).

Drill a ¼ inch hole in the second guide, being sure to drill

straight, lining it up with the hole in the plug. There is little

play in between these two, so be sure this hole and the plug

hole are exactly in the center of the bowl (figure 8).

Roll out another coil for the handle, then pull and taper

both ends like a handle for a mug. Don’t pull too thin, you

want it to hold its shape and not slump when fired. Make

the mid-section near the top of the arch pretty thick as well,

since you'll be drilling the guide hole for the rod through

that section.

When the handle has stiffened enough to work with it,

firmly attach it to the bowl. You want a strong attachment

here as this is the area where cracks are most likely to form.

If there’s any place you develop cracks, it will probably be

here. So dry slowly and be gentle.

When the handle has set, but before it’s bone dry, drill

your hole exactly in the center (figure 9). You can have more

play here, and you might want to step up one size on your

drill bit. You can always use a washer later if your hole is too

big for your spring. Still, be very careful drilling the hole, be

sure it lines up with the second guide hole in the strap of clay

at the bottom. Also don’t press too hard when drilling, you

want the bit to “cut” the clay, not push through it.

The easiest hole to drill is in your knob. Don’t go all the

way through, you just need about half an inch for your rod

to glue into (figure 10).

Slowly dry the pancaker and then bisque and glaze. When

glazing, wax as you normally would. Fire the plug separate

from the pancaker, as there’s no way to secure it into the bottom. By firing it separately, you can also glaze the area that

will eventually make contact with the bowl.

*

a ¼- to ½-inch section of the rod. Unscrew the die and you

should have a nice threaded end (figure 11).

Slide the stopper on with the bevel side up, then add a

washer and nut (figure 12). Insert the rod into the bottom

of the pancaker, through the bottom guide and finally into

the hole in the handle (figure 13). Pull the rod all the way up

(figure 14) to seat the plug then set the pancaker aside.

The next step involves measuring the rod to figure out the

final length of your stopper mechanism. Push a spring and

spare length of rod into the knob and make a mark on the

rod where the end of the spring comes to when it’s NOT under compression (figure 15). Measure that distance, and then

subtract about half an inch. This will create enough tension

to keep the plug seated securely so that it covers the opening.

For example, my overall measurement came to 1¾ in., so my

measurement for the next step was 1¼ in.

Pull the rod all the way up so the stopper seals the bowl.

Now take the measurement from the previous step and add

it to the rod. Start at the very top of the handle, measure

up toward the end of the rod, and mark this point. This is

where you want to cut the rod (figure 16). This should be a

perfect length so the stopper is firmly under pressure, sealing

the pancaker, but also leaving enough room so that the knob

can be pressed down about a half inch, opening the stopper

and releasing the batter. Disassemble everything and cut the

rod with a hacksaw. Using the die, thread the end of the rod

to make a nice “grip” for the glue.

Assembling the pancaker

Take one end of the rod and slide the spring on, daub a

fair amount of five-minute epoxy onto the end and glue it

into the knob. Make sure there is enough epoxy to hold

everything in place when it sets. Also, make sure the rod

is sticking straight out of the knob while the epoxy sets.

Note: Even though it says five minutes, wait twenty before assembling your pancaker. Slide a washer against the

spring and then insert the rod into the handle (figure 17).

Slide the assembly down through the second guide and then

flip the pancaker over (figure 18) and re-assemble the stopper.

Use a die to thread the rod, so that a nut will gracefully screw Slide the clay plug on, then slide a washer onto the rod so it

on to it. Since you are using a 1/8-inch thick rod you will want rests against the clay plug and then thread on the nut against

to get a #6–32 die. This makes a thread for a fine-thread #6 the washer. When the assembly is finished, just heat the skillet,

machine nut.

fill your pancaker with batter and you’re ready to go. n

Holding the rod with pliers, carefully start twisting the die

Keith Phillips is a full-time artist and potter in Fletcher, North

onto the rod like you would if threading a nut, being sure to Carolina. To see more of his work, go to http://khphillips.etsy.com

keep it straight. Once it is started, just keep rotating the die or visit his blog at http://blog.mudstuffing.com or contact him via

and it will carve the threads. You only need to thread about email at keith@mudstuffing.com

Creating the mechanism

26

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

27

28

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

with

Porcelain

by Antoinette Badenhorst

Photo Credit: Koos Badenhorst

Getting Started

Porcelain is desired for its purity, delicacy and translucency, but its also the perfect body

for carving and bringing out a color palette.

C

hoosing a white clay body might

look like a simple choice, but

because of the different working

characteristics between stoneware and porcelain, it’s worth exploring the

options first (see “Supply Room”, pg. 10).

For the right potter, the joy of working

with porcelain always overshadows the

potential sorrows that come along with it,

but the condition is that you understand

the medium and get in sync with it. As I’ve

heard potters say before: “I don’t know

what it is about porcelain that keeps me

coming back for more punishment, but

it’s real . . .”

A Different Material

Porcelain can be worked like other clays,

but when fired can reach a state of extreme

whiteness, becomes vitreous and often translucent, similar to glass. When tapped on, it

has a ringing sound like a bell.

Porcelain in its raw plastic state is very

fine, smooth white clay that offers a canvas

for color and textures—from a very smooth

white surface to the finest and most elegant

textural detail.

The whiteness of porcelain allows for

coloring the clay itself, painting stains and

oxides onto its surface, or glazing it with an

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

29

outcome of brilliant and often dramatic colors.

Efficiently-fired porcelain has a

glass-like character and becomes vitreous and watertight even when left

unglazed. The transition between the

fired porcelain and the glaze layer is

also less distinct than in a comparably

fired piece of stoneware. Well designed

glazes can be just as hard as the clay

and are basically scratch-proof.

This hardness and blurring of the

interface between clay and glaze are

of tremendous value to the production

potter, since these qualities limit some

2

1

The dome width predicts the width of

the base.

4

Start lifting the clay wall by making a

dent at the bottom.

5

Keep your non-dominant arm parallel

above the pot as you thin the clay.

30

trouble with glazes, particularly where

chipping and leaching are concerned.

Translucency is obtained under

specific circumstances. High percentages of glass forming ingredients like

silica and feldspar in porcelain—in

combination with thin walls and efficient firing—enhance translucency,

but might also increase the difficulty

to form and shape it. To some potters, translucency can add to the

decorating process, but many potters choose an easier working, plastic clay body that has most of the

other qualities of porcelain.

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

Throwing a Tall Bottle

Throwing tall forms is a challenge

with any clay body, and I recommend you practice throwing tall

forms using a smooth stoneware

clay first. Once you have the basic

principles down, it’s easier to apply

them to porcelain.

To get started, take 2 lbs. of porcelain and prepare a ball for throwing. The process described here is a

somewhat different approach to the

one typically used but promises to

be successful.

3

Imagine the clay to be a wave that

gets pushed upward.

6

The clay wave diminishes as the walls Repeat the dent and wave process at

become thinner and the cylinder taller. least 3 times.

May/June 2009

The width of the cylinder is determined by the width of the dome

from which you open the clay; the

wider the diameter of your dome,

the wider the base of your pot (figure 1). Once centered and opened,

start by indenting the exterior of the

clay where it meets the wheel head

or bat (figure 2). Imagine pushing

the clay upward from below rather

than pulling it from above. It’s like

water in the ocean that gathers to

form a wave before it breaks on the

shore (figure 3). Let the dominant

arm and hand control the clay on

7

Collar the cylinder to regain control if

the top becomes off centered.

10

Use rubber kidney ribs to remove

excess slurry.

the outside of the cylinder from a

secure position on the side of your

body or knees. The non-dominant

arm hangs in the air, above and parallel with the cylinder, guiding the

pot upward in the direction of the

elbow and controls the clay on the

inside (figure 4).

Repeat this process a few times.

Each time, less clay becomes available to move upward into the wall

(figure 5). Pushing the clay up from

below, rather than pulling it, eliminates the excess ring of thick clay

around the bottom or foot area of

8

the cylinder. Repeat this process at

least three times, or until the clay

is thinned out (figure 6). When you

feel the cylinder starting to swing,

or that you start losing control,

slow down the wheel somewhat

and collar the clay back in to regain

control (figure 7).

Once the desired height is reached,

continue to define the shape of the

object you intend to make (figure 8).

For shaping forms like bottles, the

non-dominant hand pushes from the

inside, while the dominant or outside hand supports the clay (figure

9

After creating the cylinder, start defining the shape.

11

Push the clay from the inside while

the dominant hand supports the clay

on the outside.

12

Use two rubber ribs to help in the final

thinning, or prior to collaring the neck.

For a bottle, begin collaring the upper

rim by encircling it with your hands.

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

31

9). Use rubber kidney ribs to remove excess slurry (figure 10), then

use them to help in the final thinning of the form for a cylinder or

bowl, or for a bottle form before

starting to collar in the neck (figure

11). To bring the neck in, repeatedly

collar then thin out the top third of

the cylinder. Use all your fingers to

support and guide the clay inward,

slowly closing the opening between

your fingers as the piece narrows

(figure 12). Next, thin out this section, throwing with your fingers

angled toward the vertical center to

14

13

Thin this collared area by angling your

fingers towards the vertical center to

further narrow the form.

Thin the neck using a rib on the outside

and a finger supporting the inside.

PotteryMaking Illustrated

Repeat the collaring and thinning

process to narrow the top until the

opening is the right diameter.

When adjusting a piece, work on

thick foam cushions and chucks to

protect the thin neck area and stabilize rounded forms. Some of these

foam chucks are custom cut to fit the

shape of the pieces I have in progress.

Tips for Working

With Porcelain

1

Always wedge clay from a few

hours to up to a day before using

it to make sure that the water content

is evenly distributed throughout the

clay ball. This also helps to orient the

clay particles into a circle or spiral. Al-

15

Create the neck of the bottle by thinning and collaring the remaining clay

with your fingertips.

17

16

32

further narrow the form (figure 13).

Repeat the collaring and thinning

process until the opening is the right

diameter (figure 14), then create the

neck of the bottle with the remaining clay (figure 15). Thin the neck

with a rib on the outside and your

finger supporting on the inside, then

finish the exterior of the form with a

rubber kidney rib (figure 16).

Allow the finished piece to set up

to leather hard on the bat then trim

it right side up while still on the bat

(figure 17) before turning it over on

a chuck and trimming a foot ring.

|

Finish the opening and the exterior

surface of the form with a rubber rib.

May/June 2009

Finished, carved porcelain vessel by

Antoinette Badenhorst.

though aged clay is stiff during the first

few wedges, it’s much better than freshly made clay and it quickly softens. Allowing the porcelain to rest after it’s

wedged is important, because it tends

to fatigue easily.

Pay special attention to centering and always cone the clay to

get all the clay particles lined up.

Many potters consider coning as

just another way of wedging, but in

many instances porcelain reminds

me of the fairy tale of the princess

that could not sleep with a pea under her mattress. The slightest little

lump or unevenness can force you

back to the beginning.

Handle the clay as little as possible to limit it from getting fatigued. I manipulate the wedged ball

into a pear shape and place it with

the small end downward on the wheel

head to take advantage of the circular movement that started forming

during wedging. I further define the

lineup of clay particles through the

coning process.

Porcelain is normally thirsty, absorbing water quickly, and collapses easily when too much water is

used. Even a more plastic porcelain

clay body functions better with less

water. Adding a spoonful of vinegar

in the throwing water gently deflocculates the clay and helps in lubricating the clay. Since porcelain shrinks

more than other clay bodies, using

less water limits the problems related

to shrinkage.

Porcelain cracks easily for different reasons. If basic rules are important for working with other clay

bodies, it becomes of the utmost importance to porcelain. Uneven thickness in clay walls and attaching pieces

of uneven dryness will result in cracking. Cracks in the bottom of a form

are usually caused by uneven thickness throughout and/or improper

compression. Some cracks in the bottoms are caused by water left inside,

which weakens the bottom. Cracks on

rims are usually caused by too much

pressure applied when trimming the

foot. Using a foam bat on the wheel

2

3

4

5

head while trimming absorbs the

shock and eliminates most rim cracks.

You can also prevent excessive pressure on fragile pieces by using sharp

tools. Metal kidney ribs and Surform

blades are some of my most important

trimming tools.

Fill a spray bottle with water and

use it to keep the pieces damp as

long as is needed while you’re working

on them. Be careful as it takes some

training of the hand and eye to prevent

delamination of walls when spraying

semi-dry pots to rehydrate them. Every porcelain body is different and

needs to be evaluated separately.

To be safe, never leave freshly

thrown work in the open air

longer than 15–30 minutes, no matter if you are working in Mississippi

or Arizona.

Here are two simple systems for

keeping unfinished pieces leather

hard for weeks while you work on

them. Invert a lidded food container,

set the pot on the inverted lid and place

the container over top of it to seal the

pots in while they are in process.

Make a damp box by taking a plastic storage box, and pouring an inch or

so of plaster into the bottom. After it

cures, dampen the plaster slab and it

will slowly release moisture into the air

within the closed container.

6

7

8

Design Considerations

When working with porcelain, there

are specific things to bear in mind in

the design stage that have a direct effect

when firing a piece. Porcelain slumps

easily so avoid large horizontal areas

that are not supported. Wide domed

lids, wide rimmed bowls and plates,

handles and spouts should have an angle of at least 45° built into the design.

Some pieces will even split or separate

during the final firing if unsupported. I

use different systems in the kiln to support my work. It’s an ongoing process

of planning and improvisation, since

my work is one of a kind and using

supports only works if the area to be

propped up is unglazed.

Porcelain utilitarian work is normally the same thickness or slightly thinner

than stoneware, but it’s still important

to be aware of possible slumping and

to design works accordingly.

Firing Considerations

Because porcelain fluxes and starts

to melt somewhat at its peak temperature, any supportive materials need to

be dusted with a refractory material

such as silica or calcined alumina. The

same refractory materials are necessary to prevent lids from sticking to

pots. I found that regular kiln wash is

not enough to prevent my pots from

sticking, so I wet each piece and dip it

in a thin layer of silica that I can wipe

off after the piece is safely fired.

Dimples in fired porcelain may be

caused by a very open, less plastic clay

body or by gasses that are either created by burn-off from plasticizers or

other organic materials that might be

trapped in the clay. Slow firing, soaking

bisqueware for 30 minutes and a soak

hold when the final glaze firing temperature is reached are all precautions

you can take to allow these gasses to

escape. For a very open clay body, it’s

sometimes useful to dampen the pieces

slightly before glazing. Be aware that

if the piece is too damp (which happens quickly with thin work), it can’t

absorb as much water from the glaze

solution, and so the glaze coating will

be too thin.

If you’re having problems with

cracks forming during the firing, they

can be prevented by down firing the

kiln, which helps to cool pieces (especially thin ones) slowly.

I consider my porcelain work as a

discovery; one that takes me to all different and interesting places. It suits

my personality and my passion. I invite

you to join me in this journey. Maybe

you will find the same joys as I do. n

Antoinette Badenhorst has worked with

translucent porcelain since the early 90’s. She

leads workshops, presentations and demonstrations both in the U.S. and internationally

and has written articles on pottery in both

Afrikaans and English. Her work is presented by leading galleries in America, South

Africa and Japan. Contact her through her

website: www.clayandcanvas.com.

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

33

WH

EN

SH FR

IPP EE

ING

YO

U

OR

DE

R

ON

LIN

E(

US

ON

LY

)

Ceramic Arts Handbook Series:

Throwing & Handbuilding

Price:

$29.95

ceramicartsdaily.org/books

866-721-3222

34

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

Throwing

Big

Wine jug made from thrown base and added thrown coils.

D

by Michael Guassardo

avid Schlapobersky and

Felicity Potter are leading

South African studio potters who have been working together in the tradition of highfire, reduction stoneware and porcelain

since 1973. Their open, working pottery studio is in the historic heart of

Swellendam in the Overberg region of

the Western Cape, South Africa.

They work in collaboration, with

David taking care of preparing the

clay, making pots and blending glazes, while Felicity decorates the work

prior to glaze firing in one of two oilfired kilns.

They make a wide range of items

including functional and decorative

stoneware and porcelain, as well as

large floor jars, urns, platters, fountains, garden and indoor containers.

David has developed a process that

combines throwing and adding coils

to create pieces up to four or five feet

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

35

in height. He demonstrates his method for making a tall vase here.

Process

Center 15 pounds of clay (figure

1). If it’s too difficult to center that

much at one time, try centering five

pounds of it at a time, one over the

other, starting at the bottom. Open

up the clay to within ½ inch of the

wheelhead (figure 2). To ensure the

base is properly worked down and

compacted, David adds a small flat

piece of clay on the base, which he

works in to release any trapped air

and compresses by pressing down

firmly (figure 3).

Next, open out the form to about

8 inches and begin to pull the clay

up to form thick walls that taper inward (figure 4). This also gives you a

thickish rim. Repeat the process, this

time adjust the pressure and your

hand position so that the cylinder

has straight walls (figure 5). Pull the

cylinder to the final height and flare

outward to form the desired shape,

about 12 inches in diameter at the

top. With a kidney rib, bevel the top

slightly outward to accommodate the

angle of the next step, which continues the outward curve (figure 6).

Tip

Compress the rim at the end of

each pull to consolidate the clay

and slightly thicken the rim. At

this stage use the kidney rib to remove any slop on the inside walls

and base.

1

Center 15 pounds of clay.

2

Open clay to ½ inch above the wheelhead.

3

Add a slab of clay to the bottom.

You are now ready to quick dry

the pot to stiffen the walls before

doing any further work. First, run a

wire tool under the base of the form

to release it from the bat. This quick

drying step creates sudden and uneven pressures that could cause

the foot of the form to crack if it

is left attached to the bat. Dampen

the throwing bat to prevent it from

burning. Using a blow torch, and

with the wheel revolving at your

throwing speed, dry the pot (figure

7). First heat the outside, then the

36

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

4

Collar the clay in and keep the rim thick.

5

Pull up the cylinder.

6

Begin adding shaping outward.

7

Dry the pot using a blow torch.

8

Score the rim then place the coil on top.

inside. After a minute or two, repeat

the drying process. The clay will

start to change color, and become

leather hard.

After two cycles of using the blow

torch, the pot should be firm enough

to handle about 10 more pounds of

clay. Roll out an 8 or 9 pound coil.

Since your pot is about 12 inches in

diameter, you’ll need a 36 inch coil.

Score and dampen the top of the pot

then place the coil on the rim. Cut

and join the two ends together (figure

8), place the coil onto the pot, but do

not fix it to the rim at this point.

Press the coil down and inward

with the wheel revolving slowly, so

that the outside of the coil is flush

with the pot and the roll is overhanging on the inside. Now you are ready

to throw again to thin out this added

coil and shape the contour to make

its transition with the pot seamless.

Throw by pulling the inside roll

up, with the wheel spinning at a

slightly slower speed than when

throwing the pot. Shape and trim

off any uneven clay. Once again,

compress the rim and prepare it for

the next coil.

Clean the outside join and address

the transition if necessary. Remove

the excess clay from the inside join

using a sharp trimming tool or rib,

and clean out any slurry from the

bottom of the pot (figure 9). Note:

When you finish throwing the coil,

the top flare should be a little exaggerated to allow for quick drying.

Dry the pot as before, using the

blow torch (figure 7). You may need

to wet the upper part of the first section prior to heating the piece, so it

does not dry out too much. Clean

up and remove any small dried edges on the rim.

Now add a slightly thinner coil

(about 36 inches in length) made

from about 5 pounds of clay (figure

10). Repeat the process of attaching

and throwing the coil as before. This

second coil should give you enough

clay to form the widest part of the

pot and start to curve the form back

in, finishing up to the shoulder of the

PotteryMaking Illustrated

|

May/June 2009

37

pot (figure 11). Clean up and dry the

pot as before. Note that the bevel at

the top edge should slope gently inwards for the final coil, which will

become the rim of the pot.

Add a final coil, rolled out from

about 2 to 3 pounds of clay. Throw

the desired neck and rim (figure 12)

and clean up the inside of the pot

and the transition as before. The final coil allows for a bit of creativity.

You can finish off these tall forms as

vases, jars, or bottles. Dry as before

and add accents like lugs, handles

and or sprigs. Your final pot will be

around 28 to 30 inches tall. n

9

Clean up the join after shaping the contour.

10

Glazing

David and Felicity usually skip

the bisque fire, but their glazing technique is the same for

greenware or bisqueware. After

spraying the entire pot with a

glaze, they add brushwork decoration using various oxides and

pigments. After thoroughly drying the pots, the work is fired to

cone 12 in a gas kiln in a reducing atmosphere.

Add the next coil and cut it to size.

11

Start to taper the form inward, using a rib to

refine the profile.