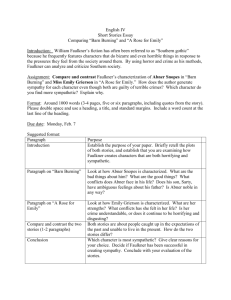

The Decay of the South: Duality and Containment in “A Rose for Emily”

advertisement

The Decay of the South: Duality and Containment in “A Rose for Emily” Michael Bolin Introduction William Faulkner, as the literary voice of the post-Reconstruction South, probes the dark corners of southern society in his short story “A Rose for Emily.” In this paper, I will examine the ways in which “A Rose for Emily” functions as a modern parable about the South as Faulkner experienced it. I will argue that below its narrative surface, the story uses an allegory for the society of its audience to reveal that the South is rotting from the inside out. Faulkner argues that the South is a moribund society that sustains itself with illusions, cruelty, and injustice, and then attempts to defend itself from the revelation of that fact through an elaborate sacrificial mechanism of contained, ritualized violence. Whether the decaying cruelties of Southern society will succeed in sustaining themselves depends on the parable’s audience. It ultimately falls to them to accept the parable’s revelation of the South’s decay. For Faulkner, whether they will do so remains an open question. I will make my argument in a few steps. I will first examine the structures that sustain the Southern society of the story, most importantly the intersection of duality and containment, paying particular attention to violations of those structures that occur in the story. I will then turn my attention to the society’s reaction to violations of its structures: the containment and destruction of the violation through a complex, symbolic sacrifice. I will conclude by drawing out a few narrative modes by which Faulkner forces his audience to face the parable’s revelation as if it pertained not to the fictional characters, but to the audience themselves. In order to provide depth to this analysis, I will occasionally refer to Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness. Although “A Rose for Emily” and Heart of Darkness have very different plots, their narrative concepts and purposes are closely tied. Broadly, they both reveal the corrupt nature of their respective societies by combining containment with duality. I do not claim to fully account for this narrative process in Heart of Darkness; rather, I will use it only as a hermeneutical tool for understanding the revelation that lies at the intersection of containment and duality. Heart of Darkness and “A Rose for Emily” are not odd partners. There can be no doubt about Conrad’s influence on Faulkner. The parallels between Heart of Darkness and “A Rose for Emily,” while perhaps unexpected, are not coincidental. Faulkner was four years old when Heart of Darkness was published, and he wrote “A Rose for Emily” when he was 31. 1 In the intervening years, Conrad’s writing profoundly shaped Faulkner’s. While still obscure, Faulkner proposed in an anonymous magazine article that “art is preeminently provincial...it comes from a certain age and a certain locality.” He admiringly qualified his thesis with only two exceptions: Eugene O’Neill and Joseph Conrad.2 In January 1925, just months prior to the publication of his first novel and four years prior to “A Rose for Emily,” Faulkner told his friend Sherwood Anderson that the two stories he admired most were Anderson’s short story “I’m a Fool” and Conrad’s Heart of Darkness.3 In October of that same year, Faulkner visited the picturesque Kentish countryside, where Conrad had been known to write. He wrote to his mother that it was the “Quietest most restful country under the sun. No wonder Joseph Conrad could write such fine books here.”4 Conrad remained on his mind for at least the next several years. In 1931, he identified his two favorite books as Melville’s Moby Dick and Conrad’s The Nigger of the “Narcissus”.5 About a year later, he reflected on his artistic development over the prior few years, writing that “I was now aware before each word was written down just what the people would do,” and he compared his growth as a writer to that of Conrad.6 This was two years after “A Rose for Emily.” Similarities of narrative style and narrative techniques between the two authors—though not, as far as I am aware, specifically between Heart of Darkness and “A Rose for Emily”—have been well-documented in Faulkner’s fiction throughout this period.7 Throughout his artistically formative years, Faulkner clearly had Conrad, specifically Heart of Darkness, on his mind. Similarities between the two stories—especially of the structural, driving sort that I will discuss—are likely, consciously or unconsciously, products of Faulkner’s admiration for, identification with, and emulation of Conrad. The Parable “A Rose for Emily” and Heart of Darkness are both modern parables that build on a narrative tradition dating to the Gospels. As parables, they construct an allegory for a specific society that communicates a lesson about the nature of that society. Beyond that general structure, a parable must have two specific characteristics, a narrative and another layer of meaning beneath the narrative surface. As a narrative, a parable must have the basic narrative elements of a story: plot structure, characters, conflict, rising and falling action, and so on. These devices can be simple or elaborate, but they must be present. Jesus’s tale of the sower is a parable, while the saying “A seed that falls on hard ground never grows” is not. It is a saying. Both convey more or less the same message, but the parable does so through a story.8 The second defining trait of parables is that their meaning, which consists of multiple layers, lies beneath their narrative surface. The moral of the Parable of the Sower concerns conversion to a new way of being, not weed growth. The story is not just a narrative; rather, as an allegory for the society, its deeper levels of meaning convey truths that may or may not be readily and easily perceived by any attentive listener.9 The purpose of the allegory is to open the audience to ways of perception that are new and even revolutionary. It might even suggest an undesirable ultimate outcome of current conditions, and then propose an alternate path which, if followed, will produce a more desirable outcome. As a parable, “A Rose for Emily” is a story that contains layers of meaning, which it discloses through an allegory for the society it addresses. The least discerning reader will recognize its narrative surface, a mystery-horror story, just as that reader might believe the Parable of the Sower to be concerned purely with agriculture. Below the narrative surface lie two layers of meaning. A mildly attentive reader will perceive the first level of meaning, which is the moral of the parable: that the South is in bed with a rotting way of life. Below the moral lies a second, deeper level of meaning: a hidden, inner meaning that cannot be cognitively understood or communicated.10 Let us pause to fully define this concept. While the moral of the parable is intended for all but the most ignorant readers, the inner meaning is meant only for a few select readers. In discussing the meaning of his parables, Jesus explains that “To you has been given the secret of the kingdom of God, but for those outside everything is in parables; so that they may indeed see but not perceive, and may indeed hear but not understand.”11 The insiders will grasp the inner meaning, while the outsiders, though they stare directly at it, will not. This is a paradox that is exemplified by the dying Kurtz: “‘I am lying here in the dark waiting for death.’ The candle was less than a foot from his face.”12 Similarly, for Jesus, the inner meaning is not hidden to the outsiders, but rather “everything is in parables.”13 The word he uses, the Greek parabolē, is often equated by Mark with the Hebrew mashal, meaning “riddle” or “dark saying.”14 Like a riddle, the inner meaning will be understood by only a privileged few, the insiders. But unlike a riddle, the inner meaning cannot be cognitively deduced from the parable. Jesus’ dictum “He that hath ears to hear, let him hear,”15 is not rhetorical, as it might seem, but rather an indication that the insiders are the ones who have already experienced the inner truth, but who perhaps do not realize what has already been imparted to them.16 Storytellers also influence the unfolding of such parables. Conrad and Faulkner have each experienced the dark truths of their respective societies, but both face the parable-teller’s quandary: they are storytellers who have knowledge of hidden realities of their societies, but they cannot impart this knowledge openly through their stories. They cannot state the facts, but they can indicate the existence of hidden truths. As a result, they embrace aporia, seeding their stories with unexplained hints. Conrad leaves his readers to aimlessly ponder such inexplicable riddles as “We live in the flicker,”17 and “The horror! The horror!”,18 while the absence of any roses in a story titled “A Rose for Emily” has befuddled generations of Faulkner’s readers. Any attempt to explain what the authors meant by these riddles, however plausible, is ultimately mere speculation. These are the recurrences of mashal, the dark stories and riddles that cannot be answered cognitively.19 Conrad grows increasingly frustrated with his inability to communicate the incommunicable, exclaiming to his audience through Marlow, “Can you see him? Can you see the story? Can you see anything?”20 Faulkner is more accepting of the futility of explanation, preferring to remain coolly ambiguous, describing in calm and precise language the uncanny and hidden reality of the early twentieth-century South. Each author must communicate what he can—the moral of the story—and merely indicate the existence of the incommunicable inner meaning. Both facets of the parable’s message are transmitted through an allegory for society. Two allegories can be drawn from “A Rose for Emily”. The first equates Emily with the post-Reconstruction Deep South: each is a relic of an old, formerly noble order that is in bed with a rotting way of life. The second interpretation equates the fictional town of Jefferson, in which the story is set, with the South. Because they both communicate the same meanings in the same way, for our purposes, it is irrelevant which interpretation is preferred. As we will see, both allegories are constructed as a combination of duality and containment. It is through the structure of the parable that the other devices of “A Rose for Emily” function. Duality The role of the parable is to reveal dark societal mechanisms. As a parable, “A Rose for Emily” issues a verdict on the dualities that sustain Southern society. A duality is a structure containing two mutually exclusive concepts that can only be fully defined as the opposite of each other.21 “It is a matter of establishing the representation of pairs of opposing values, of establishing quantitative differences between the opposing forces.”22 Dualities are modes of perception and interpretation that are unquestioned and thus generally universal within a particular society. They make society possible by providing a foundation of common perception and interpretation for all members of the society to follow. It is dualities, rather than some other framework, that serves this function because dualities explain conflict without necessitating a solution for that conflict. The South of “A Rose for Emily” follows the dualities of Northern vs. Southern, black vs. white, masculine vs. feminine, nobility vs. laborers, inside vs. outside, and acceptable vs. unacceptable behavior. They largely go unchallenged (I will address the consequences of challenging duality below), so they dominate the Southern worldview without ever being debated in terms of their validity. Since they are neither recognized nor understood by those within the social system that sustains them, they possess both potency and fragility: they are usually allowed unchecked dominion over the society’s worldview, but their dominance becomes dependent upon itself. Any challenges that do occur, whether or not they gain widespread approval, are enough to destroy the sheen of perfection that defines and sustains the duality’s dominance over perception in the society. In use, dualities restrict activity beyond directly distinguishing two opposed concepts. The duality of masculine vs. feminine, for example, has implications within Faulkner’s Southern society that it would not necessarily have in another society: that women, particularly women of high birth, are expected to be conservative, modest, domestic, and either chaste or married. While the most raw assault on a duality is the collapse of its two concepts, any breach in the duality’s implications are a threat as well. Emily does both. She, a noble Southern belle, has an extramarital affair—an indirect assault on the installed duality of masculine vs. feminine—and she has it with a working-class Northerner, which forms a direct assault on the dualities of Northern vs. Southern and nobility vs. laborers. Because it defies the dualities that govern their thought, this assault is unfathomable by those within the society. When Emily begins to be seen around town with Homer Barron, “the ladies all said, ‘Of course a Grierson would not think seriously of a Northerner, a day laborer.’”23 Of course not. Containment and the Revelation As we have seen, the society of Faulkner’s story depends on the total dominance of duality in perception. By definition, duality cannot be questioned; the opposition is total, eternal, and immutable. What happens, then, when duality is questioned? Society is thrown into disarray, for the assumptions that sustain it no longer exist—the act of questioning reveals that the dualities can be questioned, removing forever the sheen of perfection. A challenge to the established order, however small, provides the fatal hairline crack in the structure. A challenge to one duality throws all other dualities into question, as described by the Portuguese monk Fco (sic) de Santa Maria in 1697: “As soon as this violent and tempestuous spark is lit in a kingdom or a republic, magistrates are bewildered, people are terrified, the government thrown into disarray. Laws are no longer obeyed; business comes to a halt; families lose coherence.... Everything is reduced to extreme confusion.”24 Reduction to confusion is the result of a challenge to duality.25 Because duality gives social structure, its absence is experienced as an absence of social structure—in short, as anarchy.26 How does society handle a collapse of duality, and the resultant slide into anarchy? Its first resort is to contain the collapse. For my purposes, containment is a type of liminality. Liminality, in turn, comes from the Latin limen, meaning “threshold,” so I understand “liminality” to refer to the thresholds and boundaries within the space in which the action of the story takes place.27 Those boundaries form a liminal zone between two parallel worlds (an inner and an outer world), which can only be breached under special circumstances. Containment is the type of liminality in which one world encloses and hides the other, and in which the contained world is at the center—both literally and metaphorically—of the surrounding world. The inner and outer worlds possess distinct natures. Because every “tempestuous spark”28 has been contained within it, the inner world is radically defiant of the dualities of its society. As a result, the liminal experience of the inner world reduces difference and discards social structure and hierarchy, so that Liminal entities are neither here nor there; they are betwixt and between the positions assigned and arrayed by law, custom, convention, and ceremonial.... It is as though they are being reduced or ground down to a uniform condition to be fashioned anew and endowed with additional powers to enable them to cope with their new station in life.29 Containment is a convenient response to a collapse of duality: the collapse is hidden away behind liminal barriers and within a peculiar inner world. This inner world may be at the center of the society, but it is sealed off from, and unknown to, the society. Beyond mere liminal separation, the inner and outer worlds are fundamentally different. In the outer world, the dualities are respected and hold near-total power over perception, as discussed above. But in the inner world, the dualities are challenged, leading to their collapse and the destruction of the power. Dualities, in their structured potency, are present in the outer world and absent in the inner world. Because dualities play a major role in structuring perception and thought, their presence or absence can be experienced as the presence or absence of rationality. As Marlow moves closer to the interior, he notes that light and shadow blend; that Europeans and Africans intermingle, being reduced to the same equal plane and adopting each other’s cultural customs; that rationality disappears—“For a time I would feel I belonged still to a world of straightforward facts; but the feeling would not last long”30—and that even the basic tenets of civilized human behavior disappear, as illustrated by Kurtz’s use of shrunken heads as domestic decor.31 Conrad himself notes in his autobiography that In that interior world where his thought and his emotions go seeking for the experience of imagined adventures, there are no policemen, no law, no pressure of circumstance or dread of opinion to keep him within bounds. Who then is going to say Nay to his temptations if not his conscience?32 By containing the collapse of duality, the interior contains the collapse of everything that duality sustains, including society itself. Girard notes that “All these crimes seem fundamental. They attack the very foundation of cultural order...the hierarchical differences without which there would be no social order.”33 The experience of the collapse constitutes the inner truth of the parable, which is told in the outer world of society. The third layer of the parable directs the receptive listener into the interior, there to be “ground down” and bestowed with the knowledge of society’s hollowness, the knowledge of the truth behind the illusion. In “A Rose for Emily,” the collapse and the inner truth are contained within Emily’s house, the inner world, which is separated from the outer world—the town of Jefferson—by the liminal zone of the house’s yard, its walls, and even the bedroom door leading to Homer’s tomb. The barrier between house and town is rarely breached before Homer’s death and is never crossed in the three decades between his death and Emily’s.34 When the townspeople do enter the house, they find that the door to the bedroom where Homer lies is sealed shut, forcing them to violently break it down before entering the deepest interior zone.35 Once they have reached the inner world, Conrad’s and Faulkner’s characters must cope with the revelation of the collapse of duality. As I will discuss in the next section, the dualities’ collapse is ultimately experienced as “a moral victory paid for by innumerable defeats, by abominable terrors.”36 But the insiders’ reaction when the collapse is revealed goes beyond horror—though, as Kurtz demonstrates, it certainly includes that. The moment of attaining the ultimate knowledge, of experiencing the incommunicable inner nature and hidden ultimate ramifications of the forces that sustain the society, is tantamount to a religious epiphany.37 Conrad dwells not on the realization per se, but on the experience of witnessing the realization, an experience which can only be described in contradictory and ambiguous terms, as epitomized in the scene of Kurtz’s death: “ ‘I am lying here in the dark waiting for death.’ The light was within a foot of his eyes.”38 Kurtz’s gaze “could not see the flame of the candle, but was wide enough to embrace the whole universe, piercing enough to penetrate all the hearts that beat in the darkness.”39 Marlow describes Kurtz’ expression at his moment of epiphany as one “of sombre pride, of ruthless power, of craven terror—of an intense and hopeless despair. Did he live his life again in every detail of desire, temptation, and surrender during that supreme moment of complete knowledge?”40 For Conrad, that final realization of the rotten core sustaining society is, in a word, nihilistic. Faulkner shows his resignation to his inability to communicate the open truth, the inner meaning of his story, by entirely omitting any explicit reference to the moment of realization. The story concludes: “We noticed that in the second pillow was the indentation of a head. One of us lifted something from it, and leaning forward, that faint and invisible dust dry and acrid in the nostrils, we saw a long strand of iron-gray hair.”41 The characters’ reaction is never described. At the moment of realization Faulkner confronts his reader not with an eloquent description of that startling revelation, as with Conrad—but with the literal blankness of an empty page. Faulkner conveys not the revelation itself, but the sensation of reaching the interior. To read the story’s last line, as above, is to experience a moment of lonely and silent despair at the discovery of a terrible truth whose implications reverberate through the core of the society. It is the sensation that the parable-teller has experienced in the interior, as he experienced it, in a sublime and intensely personal dawning of realization and disgust—that “We live, as we dream—alone.”42 The Sacrifice The sacrifice is the mechanism that creates the horrors of the inner world, by examining its roots in, and function for, the society of the outer world. The ultimate cause of the frightening and threatening collapse of duality is the society’s reliance on a hollow and vulnerable system. But “rather than blame themselves, people inevitably blame either society as a whole, which costs them nothing, or other people who seem particularly harmful for easily identifiable reasons.”43 Just as a disease is cured by treating its cause, not its symptoms, the society’s first step toward order is not to directly seize control, but rather to reinstate the paradigm of duality.44 The challenge to the accepted structure of dualities is treated as a crime against the society, a breach that must be repaired with blood. The archetypal example is the Passion.45 The breach in the structure sustaining Southern society is addressed by Homer’s ritual sacrifice—but the disturbing and devastating revelations about the society’s rotten foundation ultimately cannot be silenced. The sacrifice varies from a simple criminal prosecution in that “the persecutors choose their victims because they belong to a class that is particularly susceptible to persecution rather than because of the crimes they have committed.”46 The sacrificial victim in “A Rose for Emily,” Homer, is chosen as a suitable sacrifice because he is easy to persecute. Homer emerges as the ideal sacrifice because he acquires three social roles: monster, scapegoat, and ultimately victim. Homer is first identified as a suitable sacrifice on two counts: he can be somehow connected to the challenge to and even the collapse of duality that causes the crisis, and the population has difficulty identifying itself with him. In mythology such a character is often represented by a monster.47 The Minotaur is halfman and half-bull, the dragon is a man whose greed manifests itself physically, and the sphinx is usually a lion with a human head. Each is partially human and animal, embodying a disconcerting collapse of duality; each signifies and is blamed for society’s ills; and each must be slain to heal society.48 The repugnance of monstrosity equates collapse of duality with disgust and places the monster outside the borders of accepted society.49 Homer is fully human, but he embodies a challenge to a crucial duality to Southern society: he is a Northerner living, albeit temporarily, in the South. Perhaps the greatest indication of Homer’s separation from the society of Jefferson is his unexplained absence, which is noticed but causes neither surprise nor alarm. The narrator dismisses the townspeople’s indifference by noting that the street paving, which Homer had been in Jefferson to supervise, had been completed.50 Homer is not connected to the society, as are the other societal insiders. He is an outsider who must be thought of in different terms—as transient, disposable, and insignificant. A problem arises: the monster may be outside society, but that fact alone does not make him responsible for the specific crisis threatening society. He is, nonetheless, held responsible for it. This is the scapegoat impulse, which brings us to Homer’s second role. As a scapegoat, he is not merely blamed for the crisis; he is equated with it.51 The line connecting him to the crisis so that the two become indistinguishable is neither rational nor justified, but it nonetheless makes the sacrifice possible. So what defines the scapegoat? We have already established how Homer’s Northern origins account for his monstrosity according to the dualist terms of the Southern town. But the scapegoat is something more than the monster. While Homer’s foreign origins—at least from the viewpoint of the town—help make him monstrous, the monster does not necessarily have to be foreign. Indeed, the Minotaur was conceived and born in Crete, while dragons are often slain by a hero from (or fighting on behalf of) their hometown or native tribe. The scapegoat, however, is strongly associated with foreign origins. The Jews of Europe, who have frequently been scapegoats for many centuries, are defined as a people largely by their foreign origins. While their persecutors may also have had foreign ancestors, the Jews’ foreign ancestry was particularly conspicuous.52 The Jews exemplify another trait of the scapegoat, that “despite [their] personal insignificance, [the scapegoat] is engaged in activities that can potentially affect the whole of society.”53 Homer, who transgresses several Southern dualities, fits the model perfectly. The scapegoat also tends to be a member of a group that once persecuted—or is perceived to have persecuted—the people who now persecute him.54 Faulkner wrote “A Rose for Emily” a full fifty years after the end of Reconstruction, but in many ways the South remained just as bitter as it had ever been, determined never to be truly vanquished even after defeat in the war. Homer, who is in Jefferson to pave the roads, is perceived to be among the despised class of carpetbaggers, Northerners who migrated across the Mason-Dixon to capitalize on the need to rebuild and modernize the South—or, in other terms, to exploit the South for a profit after having destroyed it. The unspoken charge against Homer is the invasion, occupation, and attempted transformation of the South. The charges are brought by the Confederate veterans who govern the town at the time of his murder, and the executioner is Emily, who is as much a relic of the Old South as the Confederacy is. Homer, like the dragons of legend or the Jews of Europe, is a monster because he is outside society and is a scapegoat because he can be identified with the crime. The society isolates the crime and places it entirely within Homer, then kills him, ritually killing the crime itself. Homer’s final role is as the victim who must die in order to re-establish the absolute power of the dualities.55 The society exists to restrain its members from uncontrolled violence by channeling violent tendencies into acceptable channels, such as war and the execution of criminals. If the challenge to duality goes unanswered and society dissolves into anarchy, those protections against mass violence will also dissolve. Therefore the threat of mass violence is channeled into one act of symbolic violence, which replaces mass violence, against one symbolic individual, who replaces all the other members of the society.56 This logic, “That only one man should die,” drives the sacrificial mechanism.57 Because the victim’s death must be justified on socially acceptable grounds—the victim must be somehow culpable of a crime, preferably of the one for which he is being sacrificed—the scapegoat is the ideal victim. Homer’s monstrosity, his outsider traits that make it difficult for the people of Jefferson to empathize with him, further increases his vulnerability. Homer, therefore, forms the ideal sacrificial victim. His ritual murder atones for his and Emily’s transgression of three dualities that are central to Southern society, masculine vs. feminine, Northern vs. Southern, and nobility vs. laborers. An extramarital affair would have been bad enough. An open affair between an unmarried Southern gentlewoman and a Northern carpetbagger and day laborer breaches the core of Southern society, which cannot survive the collapse of these dualities. I will now examine the sacrifice itself. The actual act of violence cannot be directly connected to its source or to its purpose, because the sacrificial mechanism itself is part of the secret. “‘Penalties no longer proceed from the will of the legislator, but from the nature of things; one no longer sees man committing violence on man.’58 In analogical punishment, the power that punishes is hidden.”59 Recognition that the dualities must be defended destroys the perception that they are unquestionable, which the sacrifice seeks to protect.60 When direct violence is used, “the desired effects are no longer produced. The mystery has been exposed.”61 Society relies on duality to control perception; to react openly to a challenge to duality is to give it credence, which is exactly what it needs to tear society down. “The existence of a debate already indicates that a decision is impossible.”62 Emily is therefore appointed as the society’s agent of violence; like a pagan priestess, she carries out the ritual sacrifice on behalf of her society. The performance of the sacrifice is highly mythical and reflects the relation of containment to the collapse of duality. The upstairs bedroom, where Emily constructs her altar, is the most inner part of the house: in addition to the yard and threshold of the house, the stairs and sealed bedroom door provide additional liminal layers of separation from the exterior world. To enter the bedroom where Homer lies, the townspeople must break open the bedroom door, rather than simply entering as they had done downstairs.63 Within this deepest, most hidden room, Emily prepares her sacrifice as a pagan priestess might. Shortly before poisoning Homer she purchases, most likely at great expense, a new set of men’s dress clothes—including a nightshirt, presumably the one he wears in death—and a set of silver toiletries on which is inscribed the initials “H. B.”64 After their purchase they do not resurface for thirty years. That scene of the tomb’s discovery speaks for itself. A thin, acrid pall as of the tomb seemed to lie everywhere upon this room decked and furnished as for a bridal: ...upon the dressing table, upon the delicate array of crystal and the man’s toilet things backed with tarnished silver, silver so tarnished that the monogram was obscured. Among them lay a collar and tie, as if they had just been removed, which, lifted, left upon the surface a pale crescent in the dust. Upon a chair hung the suit, carefully folded; beneath it the two mute shoes and the discarded socks.65 The clothes and toiletries are part of the sacrifice; they are the relics of his life that will be Homer’s companions in his tomb, just as an Egyptian pharaoh would have been entombed with his everyday possessions.66 Emily’s elaborate preparation for Homer’s death suggests the chilling premeditation of the sacrifice: “I want some poison,” she said to the druggist. She was over thirty then, still a slight woman, though thinner than usual, with cold, haughty black eyes in a face the flesh of which was strained across the temples and about the eye sockets as you imagine a lighthouse keeper’s face ought to look. “I want some poison,” she said. “Yes, Miss Emily. What kind? For rats and such? I’d recon—” “I want the best you have. I don’t care what kind.” The druggist named several. “They’ll kill anything up to an elephant. But what you want is—” “Arsenic,” Miss Emily said. “Is that a good one?” “Is...arsenic? Yes, ma’am. But what you want—” “I want arsenic.”67 Emily reveals much by revealing nothing. She stands in a trance, fixed on one purpose and devoid of any emotion at the act of killing the man she loves, having left herself behind and assumed the societal role of the priestess. This masochistic impulse to kill the thing one loves, which is tantamount to fratricide, is part of the sacrifice’s constantly shifting blame.68 Society’s defensive mechanism of indirect violence seizes complete control over her, driving her against every instinct she might have for herself.69 To the townspeople, Emily appears mad. Her actions, though, form not random madness but rather cool calculation of the cruelest sort—and the actions are not hers, but rather the defensive impulses of society acting through her. The act of violence cannot be directed against, or conducted by, any specific individual. The individuals involved must act purely in their ritual roles, on behalf of the society, because the sacrifice “aims to establish a sort of homeostasis, not by training individuals, but by achieving an overall equilibrium that protects the security of the whole from internal dangers.”70 By acting through Emily, the society avoids responsibility for the crime, utilizing a twisted circle of blame: Homer is blamed for the breach of dualities and punished to absolve that crime, but the punishment in itself is a crime, for which Emily must be blamed. Emily is a convenient resting place for the blame because she, being dead and having no descendants, can be fully blamed without being punished. While the sacrifice of Homer follows the ultimate purpose for the execution of any criminal—to isolate and kill the crime through ritual violence conducted on behalf of the society—Homer is never publicly executed. To understand Homer’s death as an execution on behalf of society, the high-profile drawing and quartering of Robert-François Damiens, who had attempted to assassinate Louis XV, provides a salient comparison. Even if Faulkner was not familiar with the Damiens case, he would certainly have known of public execution and torture, which Damiens’ death exemplifies. The plan for Damiens’ execution was that the flesh will be torn from his breasts, arms, thighs and calves with red-hot pincers, his right hand, holding the knife with which he committed the said parricide, burnt with sulphur, and, on those places where the flesh will be torn away, poured molten lead, boiling oil, burning resin, wax and sulphur melted together and then his body drawn and quartered by four horses and his limbs and body consumed by fire, reduced to ashes and his ashes thrown to the winds.71 As with the murder of Homer, Damiens’ execution is meticulously planned and methodically conducted, with the ultimate goal of isolating the crime within the criminal’s body and destroying it. But unlike Homer’s destruction, Damiens’ destruction is total and public. The maximum amount of agony possible is inflicted over several hours before thousands of witnesses, including his wife, demolishing Damiens’ humanity and his will to live.72 His body is then hacked and torn to pieces and burned for several hours until nothing remains but fine ash.73 Homer’s fate is far gentler. Presumably, arsenic in his food or drink results in his fairly quick and painless death. His body is never directly harmed, save by the natural forces of decay. And his death, which takes place in complete secrecy, remains undiscovered for three decades. Homer’s sacrifice, while premeditated and ritually prepared, leaves a margin for failure. Homer cannot be sacrificed in 1897 as Damiens was in 1757 because modern society, even though capital punishment is still widespread in the United States, has moved beyond direct awareness of the scapegoat mechanism at work in capital punishment. Homer’s secret destruction therefore can neither be public nor total, but is rather conducted in secret and in a manner that preserves the body as much as possible. The implications are profound: the absence of public torture and execution does not indicate a more just or humane society. It indicates instead that the old cruel sacrificial mechanism has merely moved out of public view and into a secret, contained space, and that punishment has moved away from the criminal’s body and against the criminal’s soul.74 But despite the layers of concealment between the crime and the punishment, there is no doubt that Homer has died because he challenged the South’s dualities: his body rots on the very bed where he and Emily likely consummated their affair, and where (though Faulkner never explicitly refers to necrophilia) their sexual contact possibly continued beyond his death. His death and the crime are even physically fused: by the time his corpse is discovered, it has become “inextricable from the mattress on which it lay.”75 When combined with the certainty that the victim has been unjustly sacrificed, the attempt to place a margin of doubt between the crime and the execution, between the punishment and the criminal, reveals the sacrifice’s corrupt nature in a way that can be—and, in light of Emily’s mortality and the townspeople’s curiosity, must be—discovered. The sacrifice’s unchanged purpose, to preserve the illusions of dualities by destroying a victim who is objectively innocent, is revealed to any insider who breaches the liminal zone and enters the inner world. Disconnection of the Sign Let us consider the details of Homer’s entombment and their implication for the sacrifice’s goal of hiding not just the collapse of duality, but the very existence of such a corrupt and cruel structure. Ordinarily, a ritual entombment would act as a rite of passage into the underworld. Homer’s tomb draws on burial rites ranging from ancient Egypt, where pharaohs were entombed with their possessions, to the modern West, where the dead are buried in their best dress clothes. Homer’s entombment should be a symbolic sending-off, with Homer dressed presentably in his new set of dress clothes and with a few expensive, personal possessions—the monogrammed silver toiletries—to signify that his high rank in this life will carry into the next. But it does not mean these things at all. While those rituals are carried out, they become completely perverse. Homer is clothed not in his new suit, but in a simple nightshirt. The suit instead rests on a nearby chair, neatly folded, as if taunting him. The toiletries are in their proper place, beside the bed, but reflect Emily’s wealth, not Homer’s; indeed, any such sign of wealth in the tomb of a working-class construction worker is inherently artificial and misplaced. Most significantly, the bedroom is not Homer’s proper resting place. It is not only above ground, but on the second floor of the house, in a location that is secret but that must ultimately be discovered and disturbed. Emily cannot have thought that she and Homer would lie there forever, at least not literally. Homer receives the horrific and unnatural dishonor of being allowed to rot above ground, exposed to the air and to the viewing of the disgusted townspeople, an unparalleled insult that dominates stories as far back as Homer’s76 Iliad and Aeschylus’ Antigone. In those stories, at least, the insult of going unburied was transparent; in “A Rose for Emily” it is just as insulting but packaged as its opposite, an honorable entombment. The disjointed symbolism of Homer’s entombment, wherein an honor is actually a perverse insult, is more deeply structural than a mere reversal of expectations. Faulkner invokes mythical motifs but disconnects them from their usual mythical meaning. Let us think of each motif as a sign that consists of a signified, a signifier, and the relationship between the two: Signifier Proper burial rites Signified Passage to underworld Insult77 Faulkner disconnects the signifier from the signified to which it might be expected to point. In this case, he disconnects Homer’s highly ritualized burial rites from a respectful sending-off into the underworld. Reversing the meaning of a mythical motif is no small gesture: “A Rose for Emily” is full of mythical motifs, and once one has been challenged, none of them are safe. Indeed, Homer’s entombment is not the only reversal of a motif. We have already seen that Homer’s sacrifice, which consumes much of the story, is both scrupulous in including mythical details and uncompromising in reversing the expected course of the sacrifice, its outcome departing radically from Damiens’ archetypal sacrifice of 240 years prior. This radical departure from the expected is undertaken not for the sake of uniqueness, but to point to the incommunicable inner meaning of the parable and to reflect the decay of Southern society. Only a reversal of the accepted meanings of motifs can point to an inner meaning that is itself a reversal of the accepted structure.78 And only a story that disconnects motifs from their expected meanings can capture the massive misappropriation of symbols to their meanings that makes possible the corruption of the society. “It is society that defines, in terms of its own interests, what must be regarded as a crime: [the definition of a crime] is not therefore natural.”79 Homer is treated as a criminal, but his only offense has been to challenge the dualities of the story’s Southern society. He is an innocent victim who is punished for an offense that is a crime in name only. This injustice is made possible when dualities, which are really just modes of perception, are mistaken for natural laws and universal truths. In practice, the results are often ugly: racism, sexism, xenophobia, and all their consequences. In “A Rose for Emily,” those consequences include betrayal, murder, and necrophilia. That misplacement of perception as substance is at the heart of the society’s illusions, which, as we have seen, the parable seeks to reveal and to reject. Reflexive Interpretation The true purpose, means, and outcome of the sacrifice are revealed by the parable. The time and place of “A Rose for Emily” are central to the potential meaning and interpretation of the story. One of the necessary characteristics of a parable is that, when it is told, it is set within, and targeted at, a specific society. The Parable of the Sower is clearly set within and meant for an agricultural society, particularly one that farms on land that is difficult to cultivate, such as the lands of the ancient Israelites. The Parable of the Good Samaritan explicitly names its societal context, as indicated by its title, and its moral cannot be understood without first understanding the Israelites’ view of the Samaritans.80 As a parable, “A Rose for Emily” targets the postReconstruction Deep South, which forms both the story’s setting and its intended audience. It assumes the existence two Souths: a fictional one within the story, and a real one outside of the story—the society in which Faulkner lives. Those two societies, one inside the story and one outside, are in the same place at the same time. Because of the fragmented chronology of the story, I will attempt to determine the date of Emily’s death. In 1894 Colonel Sartoris remits Emily’s taxes in response to her father’s death, which presumably occurred in or shortly before that year.81 At the time of her father’s death, around 1894, Faulkner tells us that Emily is about 30 years old.82 Homer’s death occurs two years later, which coincides with an indication that Emily is “over thirty” when she purchases the arsenic with which to kill Homer.83 About thirty years later, the younger generation that has taken control of the town attempts, in vain, to reinstate Emily’s taxes.84 She dies some unknown amount of time later. If we assume that Emily’s father dies just before Emily’s taxes are remitted in 1894, that Homer dies in 1896, and that Emily dies exactly 30 years later, we can place Emily’s death in 1926 at the earliest—three years before Faulkner wrote the story. The story's geographical location is identical to that in which Faulkner's audience lives, the Deep South. Like many of Faulkner’s short stories, “A Rose for Emily” is set in the fictional town of Jefferson in the fictional Yoknapatawpha County, which was modeled after Faulkner’s Mississippi hometown.85 While the story can be appreciated by people from any region, Faulkner’s initial intended audience would have been Southern; his stories, at least the early ones such as “A Rose for Emily”, were written about Southerners and for Southerners. The parable’s specific time and place are equated with the time and place of its intended audience. Faulkner thus places the parable on top of his audience, leaving no space between the two. His awareness of the space, or lack of space, between parable and audience adds new complexity to the parable. The parables of the Gospels allow this space; they are stories that occur within their audiences’ societies, and that occasionally occur in a specific geographic space, but they are never given a specific chronological space. Faulkner identifies this traditional view on the parable with the older generation of the town, who after Miss Emily’s funeral gather on the porch and the lawn, talking of Miss Emily as if she had been a contemporary of theirs, believing that they had danced with her and courted her perhaps, confusing time with its mathematical progression, as the old do, to whom all the past is not a diminishing road, but, instead, a huge meadow which no winter ever quite touches, divided from them now by the narrow bottleneck of the most recent decade of years.86 From this perspective, an ambiguous separating space is maintained between parable and audience. While the parable is presumed to contain lessons that transcend that separating space, the audience can selectively apply those lessons to their own society. The space allows the caveat that the parable does not necessarily apply to the audience’s society, only that it might, if it so pleases the audience. Its moral and inner meaning is taken as gentle advice. But, because of the brutal and disturbing nature of the inner meaning of “A Rose for Emily,” the parable loses its effectiveness if this comfortable space is maintained. “A Rose for Emily” challenges this space, and in eliminating it, Faulkner forces his audience to confront the corrupt nature of their society without any escape. Because the parable’s audience belongs to the society in question, its interpretation of the parable is necessarily—and perhaps unwittingly—an interpretation of itself. The acts of narrative interpretation and of self-scrutiny become one action, each inseparable from the other.87 The conditions of the story are understood as closely reflecting the conditions of society, while the story’s outcome is taken as the natural conclusion of those societal conditions.88 The story’s moral, therefore, becomes a dictum for society, an alternate path that if followed will adjust conditions to provide a desirable outcome.89 This narrative process, which I have labeled reflexive interpretation, almost literally draws the audience into the parable. Faulkner’s unusual use of collective narration, using the first-person plural “we” as the story’s narrator and protagonist, further equates the characters with the audience by using a pronoun that could include the audience. Collective narration conveys an undefined group of people, observing and occasionally interacting with the story together, and ultimately receiving the revelation together. The audience is implicitly included in the group-protagonist. Once the audience and the characters have been equated, the next question is whether the members of the society—and of the audience—will choose the alternate path. It is the younger generation within the story that views the revelation as a direct indictment of the audience’s society. The older generation, which consists of Confederate veterans and other irrational yet genteel guardians of the old order, is married to the Old South; they, like Kurtz, cannot see its decay even when it stares them in the face. In contrast, the younger generation, which has largely inherited control of the town by the time of Emily’s death, [“Then the newer generation became the backbone and the spirit of the town....”] is far enough removed from the old order that they can receive the revelation of its corruption. But while they can receive the revelation, the audience is never told whether they choose to, or whether they instead follow their forebears in ignoring it. For as we have seen, at the moment of revelation, the sickening shock of realization passes from the characters to the audience. The space between audience and story completely collapses; the choice to receive the revelation lies not with the characters but with the audience. And even if the revelation is ignored, it cannot be ignored in the manner of the older generation of characters, who never directly faced the revelation as the audience does in the story’s final paragraphs: The man himself lay in the bed. For a long time we just stood there, looking down at the profound and fleshless grin. The body had apparently once lain the the attitude of an embrace, but the long sleep that outlasts love, that conquers even the grimace of love, had cuckolded him. What was left of him, rotted beneath what was left of the nightshirt, had become inextricable from the bed in which he lay....90 This is the pure physical and emotional manifestation of Southern society as Faulkner sees it; this is the sensation of experiencing the inner truth, as far as Faulkner can communicate it. The full culmination of the society’s corruption—the false dualities, the unjust and brutal sacrifice of an innocent victim, the deception of the sacrifice’s containment, all of which are ultimately lies and bigotry and pointless violence—stares you in the face. It is brutal, raw, and undeniable. That the society’s corruption is to blame for the sacrifice, and that the blame for sustaining that system rests in part with each member of that society, is as tangible as the corpse that is only a few feet away. Denial is impossible, as put by Shakespeare: Gloucester: Say that I slew them not? Lady Anne: Then say they were not slain: But dead they are, and, devilish slave, by thee.91 Conclusion The mechanism by which Faulkner’s Southern society causes atrocities is dark and elaborate. The society depends on dualities, modes of perception and interpretation that are misappropriated as natural laws and universal truths. When they are enforced as such, the inevitable result is the death of an innocent victim for a crime that never existed. The dualities’ sacred status and the belief that to violate it is an intolerable crime are the hidden lies upon which Southern society is built. When played out to their natural conclusion, these premises for the society are revealed to be illusions. For Faulkner, Southern society uses cruelty to preserve a system that lives by cruelty, utilizing a decaying, self-destructive mechanism of violence that “will produce nothing but victims.”92 The revelation of Southern society’s corruption, and the use of reflexive interpretation to implicate the audience in that corruption, lies at the heart of Faulkner’s parable. Faulkner modernizes the parable by transforming it from an instructive tale about the society to a tale that is the society. It is a forceful parable that cannot be passively dismissed: its revelation will either be accepted and the society changed, or it will be rejected and the society will continue on its moribund path. Because the parable has eliminated the comfortable space between story and audience, the audience can never again claim blamelessness. Knowledge of the parable’s revelation is all that is needed to change the society’s course, for “Once understood, the mechanisms can no longer operate; we believe less and less in the culpability of the victims they demand. Deprived of the food that sustains them, the institutions derived from these mechanisms collapse one after the other.”93 Faulkner leaves it up to his audience to decide whether to accept the revelation—but in either case, they have been made vividly aware of the inhuman consequences of the status quo. They are no longer innocent if those inhuman consequences continue to occur. Any future blood is on their hands. Acknowledgments I wish to thank my mentor for this project, Professor Brenda Deen Schildgen, for her patience, her advice, and her significant dedication of time to this project over the course of five months. I am also indebted to Professor Marijane Osborn, who has been a wonderful unofficial mentor to me for two years, and with whom I developed the beginnings of this project. Additional thanks go to Hope Medina, MURALS, the Davis Honors Challenge, and the Department of Comparative Literature for their sponsorship of this paper. Notes 1. Blotner 632. The article, titled “American Drama: Eugene O’Neill,” was published in the “Books and Things” column of the Mississippian on 3 Feb. 1922 under the pen name “W. F.” 2. Blotner 388. 3. Blotner 476. 4. Blotner 715. 5. Blotner 703. 6. Blotner 457-8, 521, 703. 7. Kermode 24. 8. Kermode 24. 9. Levi-Strauss 14. 10. Mark 4:11-12, cited in Kermode 29. 11. Conrad, Heart of Darkness 104. 12. Mark 12, cited in Kermode 31. 13. Kermode 23, 25. 14. Kermode 29. 15. Kermode 2-3. 16. Conrad, Heart of Darkness 7. 17. Conrad, Heart of Darkness 105. 18. Bruns 627-8. 19. Conrad, Heart of Darkness 40. 20. Levi-Strauss, The Raw and the Cooked 1. 21. Foucault, Discipline and Punish 104. 22. Faulkner 55 23. Girard 13. 24. Girard 30. 25. Turner 166-7. 26. Turner 94-5. 27. Girard 13. 28. Turner 95. 29. Conrad, Heart of Darkness 18. 30. Conrad, Heart of Darkness 73. 31. Conrad, A Personal Record, xviii. Cited in Watts 49. 32. Girard 15. 33. Faulkner 52. After the younger generation of town officials fails to reinstate Emily’s taxes, the narrator lays out a chronology: “So she vanquished them, horse and foot, just as she had vanquished their fathers thirty years before about the smell. That was two years after her father’s death and a short time after her sweetheart [Homer]—the one we believed would marry her—had deserted her. After her father’s death she went out very little; after he sweetheart went away, people hardly saw her at all.” 34. Faulkner 60. 35. Conrad, Heart of Darkness 107. 36. Girard 55. 37. Conrad, Heart of Darkness 104. 38. Conrad, Heart of Darkness 106. 39. Conrad, Heart of Darkness 105. 40. Faulkner 61. 41. Conrad, Heart of Darkness 40. 42. Girard 14. 43. Girard 101. 44. Girard 100-3. 45. Girard 17. 46. Girard 35-36. 47. Girard 48. 48. Girard 31-34. 49. Faulkner 58. 50. Girard 36. 51. Cf. Girard 1-11. 52. Girard 17. 53. Girard 32, 104, 115. 54. Girard 16. 55. Girard 112-13. 56. Girard 112. 57. Marat, Jean-Paul, Plan de legislation criminelle, 1780. P. 33. Cited in Foucault, Discipline and Punish 105. 58. Foucault, Discipline and Punish 105. 59. Girard 116. 60. Girard 116. 61. Girard 112. 62. Faulkner 60. 63. Faulkner 57. 64. Faulkner 60-61. 65. Cf. Girard 113. 66. Faulkner 56. 67. Cf. Girard 125-48. 68. Turner 174. 69. Foucault, “Society Must Be Defended,” 249. 70. Foucault, Discipline and Punish 3. 71. Foucault, Discipline and Punish 3. 72. Foucault, Discipline and Punish 5. 73. Foucault, Discipline and Punish 29. 74. Faulkner 60. 75. While there is no direct evidence that Faulkner intended to draw the parallel, it should not escape us that the character of “A Rose for Emily” and the poet of the Iliad share a common name. 76. de Saussure 65-8. 77. Turner 166-68. 78. Foucault, Discipline and Punish 104. 79. Kermode 24-5, 34-9. 80. Faulkner 50. 81. Faulkner 54. 82. Faulkner 55-6. 83. Faulkner 52: “So she vanquished them, horse and foot, just as she had vanquished their fathers thirty years before about the smell [of her father’s body].” 84. Blotner 644. 85. Faulkner 60. 86. Bruns 627-36. 87. Bruns 633-4. 88. Kermode 4, 24, 28-9. 89. Faulkner 61. 90. Richard the Third, I.ii.88-90. 91. Girard 113. 92. Girard 101. Bibliography Blotner, Joseph. Faulkner: A Biography. Vols. 1 and 2. New York: Random House, 1974. Bruns, Gerald L. “Midrash and Allegory: The Beginnings of Scriptural Interpretation”. The Literary Guide to the Bible. Ed. Robert Alter and Frank Kermode. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard UP, 1987. Pp. 625-46. Conrad, Joseph. “Heart of Darkness”. Heart of Darkness and The Secret Sharer. New York: Bantam Dell, 2004. Pp. 1-117. Conrad, Joseph. A Personal Record. London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1919. P. xviii. Faulkner, William. “A Rose for Emily”. Selected Short Stories of William Faulkner. United States: Random House, 1960. Pp. 49-61. Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage Books, 1995. Foucault, Michel. Society Must Be Defended: Lectures at the Collège de France 1975-1976. Trans. David Macey. United States: Picador, 2003. Girard, René. The Scapegoat. Trans. Yvonne Freccero. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins UP, 1986. Kermode, Frank. The Genesis of Secrecy: On the Interpretation of Narrative. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard UP, 1979. Levi-Strauss, Claude. The Raw and the Cooked: Introduction to the Science of Mythology. Vol. 1. Trans. John Weightman and Doreen Weightman. New York: Harper & Row, 1969. Levi-Strauss, Claude. Structural Anthropology. Trans. Claire Jacobson and Brooke Grundfest Schoepf. New York: Basic Books, 1976. de Saussure, Ferdinand. Course in General Linguistics. Trans. Roy Harris. Ed. Charles Bally and Albert Sechehae. London: Gerald Duckworth & Co. Ltd., 1983. Turner, Victor. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. New Brunswick: Aldine Transaction, 1969. Watts, Cedric. “Heart of Darkness”. The Cambridge Companion to Conrad. Ed. J. H. Stape. Cambridge, England: Cambridge UP, 1996. Pp. 45-62.