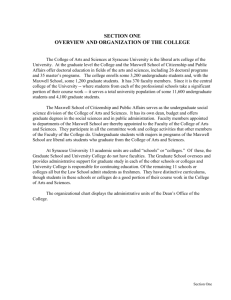

rand understanding productivity in higher education

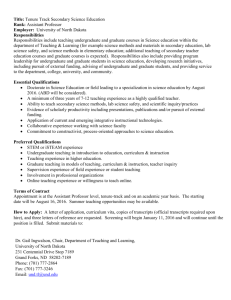

advertisement