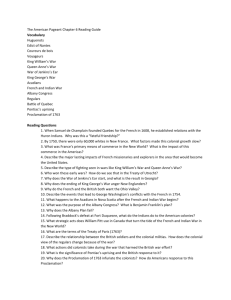

the politics of proclamation, the politics of commemoration the Royal

advertisement