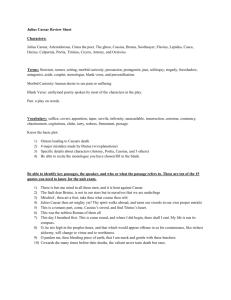

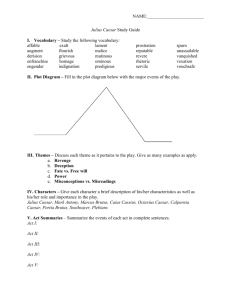

Julius Caesar - Cape Tech Library

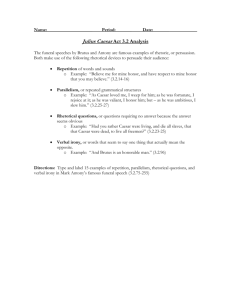

advertisement