Discerning Culture from Christianity in Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn

advertisement

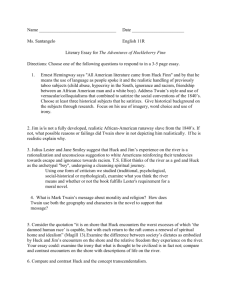

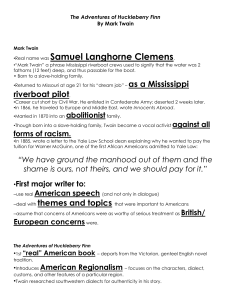

Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn deals with religious and cultural themes in the nineteenth-century setting of the banks of the Mississippi River. Discerning Culture from Christianity in Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn Michael Taylor S aints shout, congregations croon, and preachers pray as Mark Twain wades through the Christian communities lining the Mississippi, observing the American Christian culture and the need for American Christians to discern between Christianity—an evolved culture—and Christ. In The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Twain presents a critique of American Christianity and its hypocritical appropriations of doctrine not to undermine Christianity, but rather to motivate Christians to reconvert to Christ. To build his critique, Twain reveals the corruptions of those Christians living along the Mississippi River (referred to in this paper as the Mississippi Christians), presents Jim as the Christian ideal, and prescribes Huck’s resurrection of conscience as the conversion necessary to bring Christ back into American Christianity. Twain on the Mississippi Through his young hero, Huck, Twain travels the Mississippi reliving Twain’s own boyish adventures. Like Huck, young Twain enjoyed exploring the Mississippi River’s natural landscapes, navigating the great waters on jury-rigged rafts, and cooling off in swimming holes more than he enjoyed sitting through synthetic Sunday morning sermons.1 Through Huck, Twain also recreates his own experiences attending Sunday morning Christian rendezvous: Sabbath gatherings for the verbal exchange of Christian ideals. Twain recognized that such exchanges seldom translated into the lives of the theological traders. It is these common traders of ­theology, who say much but do little, that Twain denounces throughout his novel by juxtaposing Huck’s moral development outside of church and his Christian community to the moral dearth of the church-going ­Mississippi Christians. Americana As seen through Huck, Twain’s frustration with, and thus, his critique on Christianity stems from the Mississippi Christians’ failure to demonstrate the morals they teach. Twain targets the manner in which professed believers practice their beliefs, not necessarily in the content of their declarations. Twain had witnessed the confusion of altered doctrines firsthand and had developed a deep animosity toward the hypocrisy imbedded in the lives of self-proclaimed preachers and saints. As a result, Twain’s novel impugns the widespread hypocritical culture Americans called Christianity. Twain does not assert that his philosophy is absolute, as did many of the preachers of his day, but rather he seeks to motivate the religious masses to measure their practices against the morals they preach. In one of his many biographies, Twain is quoted to have claimed, “I would not interfere with any one’s religion, either to strengthen it or to weaken it . . . it may easily be a great comfort to him in this life—hence it is a valuable possession to him.”2 This reemphasizes the fact that Twain was not a religious crusader; he was simply an admonisher hoping to encourage religious individuals to rededicate their lives to the foundational moral codes they profess instead of ignorantly dehumanizing others in the name of Christ. Men have used and continue to use religion as a persuasive tool or as justification for dominating others. In his essay “The Lowest Animal,” Twain explains that “man is a Religious Animal . . . He is the only animal that loves his neighbor as himself and cuts his throat if his theology isn’t straight. He has made a graveyard of the globe in trying his honest best to smooth his brother’s path to happiness and heaven.”3 Here Twain attempts to awaken his readers to the dehumanizing effects of forcing their beliefs on others. Furthering this idea, Twain also exclaims, “Zeal and sincerity can carry a new religion further than any other missionary except fire and sword.”4 This brief but poignant observation reveals the often-overlooked reality that the majority of Christians were converted by fire or sword, not necessarily because they had sincere hearts or a pioneering purpose. Thus, Christianity has become a conglomeration of cultural traditions rather than of pious protectors of Christlike morals. Such are the Mississippi Christians Huck crosses in his adventures: they follow traditions, appropriations of doctrines, not Christ. In Huckleberry Finn, Twain expresses the need to rediscover religion in the debris of traditions passed off as Christianity. Critiquing American Christianity, Twain explains, “If Christ were here now, there is one thing he would not be—a Christian.”5 As witnessed during Twain’s upbringing 46 Americana on the banks of the Mississippi and through Huck’s adventures among corrupt Christians, this statement proves tenable. A comparison of the American Christian culture with the biblical accounts of Christ reveals that Christ would not associate with such abusers of His name. Rather, He would reprove those, who misinterpret, alter, and adulterate His teachings. The Mississippi Christian Landscape As Huck and his friends define the laws of their gutsy gang, Twain introduces the Mississippi Christians’ first flaw that Christ taught against: blind obedience. Tom Sawyer, the gang’s leader, answers his cronies’ inquiries of why he will not accept their more pragmatic plans: “Because it ain’t in the books so—that’s why . . . Don’t you reckon that the people that made the books knows what’s the correct thing to do? Do you reckon you can learn ‘em anything?”6 Tom articulates the irrefutability of written laws within the Mississippi Christian culture. Early on in the novel, Miss Watson, one of Huck’s adoptive parents, also displays this tendency to unquestioningly ­follow the letter of the law. Huck explains, “Then Miss Watson she took me in the closet and prayed, but nothing come of it.”7 The Bible does mention that prayers should be uttered behind closet doors8; however, it is more ­likely that Christ was teaching that prayers should be private, rather than public, not that all prayers must be uttered in literal closets. Twain re­emphasizes this communal flaw of blind obedience as Tom again argues with Huck about the necessity of following the books: “It don’t make no difference how foolish it is, it’s the right way—and it’s the regular way. And there ain’t no other way.”9 Concluding the novel with this repeated dis­sonance reveals the strong communal indoctrination local Christian authorities achieved. Tom, who was left within society, was unable to break away from the traditions of the communal books. Multiple problems arise when individuals build a Christian commun­ ity strictly on what is in the books. First, books can be endlessly interpreted according to their readers’ pleasures and prejudices. And second, Christ taught against blind obedience to books. Christ did not undermine the need for or importance of books, but understood the unavoidable fact that men will interpret books as they want to, leading to an eternal battle of points rather than purpose. Christ provided the ultimate example of how to embody the wisdom gained from books, teaching that within Christianity there are two laws that must trump all others: 47 Americana The first of all the commandments is . . . thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind, and with all thy strength . . . And the second is like . . . Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself. There is none other commandment greater than these.10 In other words, if any teaching, tradition, or book takes precedence over expressing one’s love for God or for others, it is not of Christ. It is not Christian. The Mississippi Christians’ blind obedience leads them to create a totalizing definition of civility. The Mississippi Christians’ definition of civility derives only from outward appearance. Huck explains, “The Widow ­Douglas . . . allowed she would sivilize me; but it was rough living in the house all the time. And so . . . I got into my old rags, and my sugar-hogshead again, and was free and satisfied.”11 According to Widow Douglas, that which made Huck feel “free and satisfied” was uncivilized. Naturally a well-groomed exterior is welcoming; however, does such grooming define civility? Is outward civility the ultimate goal of Christianity? Is this how the Bible admonishes its believers to act? No. “For the Lord seeth not as man seeth; for man looketh on the outward appearance, but the Lord l­ooketh on the heart.”12 The Lord looks past old rags and sugar-hogshead and accepts what lives underneath. Later on, Huck also expresses this notion following the cultural tradition that one’s outer appearance reflects one’s godliness. Of the thief King, Huck admits, “I never knowed how clothes could change a body before . . . before, he looked like the orneriest old rip that ever was; but now . . . he looked that grand and good and pious that you’d say he had walked right out of the ark.”13 How do Miss Watson, the King, and their fellow ­Christians compare to the Pharisees in Christ’s biblical accusation? Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! For ye are like unto whited sepulchers, which indeed appear beautiful outward, but are within full of dead men’s bones, and of all uncleanness. Even so ye also outwardly appear righteous unto men, but within ye are full of hypocrisy and iniquity.14 The Mississippi Christians’ tendentious focus on the exterior enforced a natural, psychological hierarchy, which led directly to more destructive attempts at civilization than Miss Watson’s prescribed change of clothes. During slavery in America, this superficial Christian code labeled blacks as the epitome of incivility, thus justifying their mistreatment. As a product of his culture, Huck ignorantly utters many such generalities. Of Jim, Huck states, “He had an uncommon level head, for a nigger,”15 48 Americana implying that the majority of blacks are unintelligent; Jim’s wit is an outlier. Later on, Huck quotes the then common locution: “give a nigger an inch and he’ll take an ell,”16 expressing the blacks’ ungrateful desire and natural drive to take advantage of even the most minute generosities. And yet again as Huck sees Jim’s love for his family, Huck innocently suggests, “I do believe he [Jim] cared as much for his people as white folks does for their’n. It don’t seem natural, but I reckon it’s so,”17 announcing the Mississippi Christians’ ignorance toward the blacks’ human emotions. The Duke and King provide the final demoralizing generalization as they question who stole their money: “Do you reckon a nigger can run across money and not borrow some of it?”18 declaring outright that blacks are not only unintelligent, ungrateful, and passionless, but are also thieves. Labeling the blacks as such insensate beings allowed the Mississippi Christians to justify their unchristian racism. One form of such racism appeared as Mississippi Christians began redefining laws to place blacks outside of white protection. The first redefinition was of the base Christian commandment: “Judge not, that ye be not judged.”19 The Mississippi Christian law seemed to become: judge not unless against blacks for blacks are naturally corrupt and culpable. This is observed most explicitly as Huck’s community quickly changes the blame of Huck’s sudden disappearance from his abusive, drunkard of a father, Pap, to Jim, a runaway but otherwise innocent slave: “Before night they changed around and judged it was done by a runaway nigger named Jim.”20 They judge Jim almost immediately, “before night,” despite the hard evidence against Pap. Jim is below the law; Pap’s whiteness places him above it. Thus, Jim is automatically culpable and Pap is automatically pardoned. The self-declared freedom to judge blacks led the Mississippi Christians to distort another founding law: “Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor.”21 This doctrinal damning of dishonesty became excusable toward blacks, for the blacks had been labeled as insensate and incapable of comprehending a simple principle like honesty. Such is Miss Watson’s mindset. Jim explains: Well, you see, it ‘uz dis way. Ole Missus—dat’s Miss Watson—she pecks on me all de time, en treats me pooty rough, but she awluz said she wouldn’ sell me down to Orleans . . . Well one night . . .I hear ole missus tell de widder [slave trader] she gwyne to sell me down to Orleans, but she didn’t want to, but she could git eight hund’d dollars for me, en it ‘uz sich a big stack o’ money she couldn’ resis’.22 49 Americana Going against her word, Miss Watson agrees to sell Jim for the extra profit. However, Miss Watson is not punished for her dishonesty; rather, she is rewarded for it. There is no punishment because, according to the new law, she had committed no crime. Such discriminating dishonesty led to the falsification of another ­crucial commandment: “Thou shalt not steal.”23 The new commandment declared that blacks shall not steal, especially when it involves stealing back their own enslaved children in order to reunite their family. Huck struggles to break away from this new law as Jim begins expressing his intentions of stealing his children after gaining his own freedom. Huck recalls, “Here was this nigger which I had as good as helped to run away, coming right out flat-footed and saying he would steal his children—children that belonged to a man I didn’t even know; a man that hadn’t ever done me no harm.”24 Huck’s stirring conscience displays the extent of his community’s indoctrination of contorted Christianity: Huck feels guilty for helping Jim rejoin his family because Huck’s community had taught him that it was wrong. Huck had been taught never to help a nigger. Huck knew that according to the communal law, blacks were not allowed to reclaim their children after the whites had already stolen them. Each falsification of one commandment led to another, greater distortion until finally the seriousness of even the most commonsensical commandment diminished. “Thou shalt not kill”25 became thou shalt not kill unless to settle a century-long, baseless family feud.26 Step by step these adaptations of the core Christian doctrines lead to the most sickening scene throughout all of Huck’s adventures as grown C ­ hristians—the Shepherdson men—hunt down two brainwashed Grangerford youth ­ because Harney Shepherdson and Miss Sophia Grangerford eloped: “Bang! Bang! Bang! Goes three or four guns . . . The boys jumped for the river—both of them . . . the men run along the bank shooting at them and singing out, ‘Kill them! Kill them!’”27 Is Twain’s earlier statement of Christ’s disaffiliation with the Mississippi Christians so farfetched? Are the Shepherdsons Christian? They go to church hours before pulling their triggers, a church where they are taught “all about brotherly love . . . faith and good works.”28 While the two Grangerford children swallow bullets, the Mississippi Christians swallow “camels” while straining at “gnats.”29 Focusing only on the minutia of Christianity—the books, the prayers, the sermons—instead of following Christ’s two ultimate commandments 50 Americana blinds the Shepherdsons, Grangerfords, and their community to their own corruption. What puzzles Huck most is how these actions result from such apparent goodness. Despite these obvious debasements of Christianity, the Christians Huck encounters seem extremely pious. They fill their homes with “good books.”30 They attend Sunday worships and openly discuss ­matters of “faith, and good works, and free grace”31; they even sing out songs of “a-amen! Glory, glory hallelujah!”32 Describing Colonel Grangerford, Huck explains, “He was sunshine most always—I mean he made it seem like good ­weather.”33 Through Huck’s praise of Colonel Grangerford, Twain suggests that Mississippi Christians make everything seem like “good weather” to reroute their own hypocritical hurricanes. The Mississippi Christians’ project a front of perfection while deflecting the repercussions of their actions. They provide a modern embodiment of Christ’s biblical reproof: This people honoureth me with their lips, but their heart is far from me . . . in vain do they worship me, teaching for doctrines the commandments of men. For laying aside the commandment of God, ye hold the tradition of men . . . Full well ye reject the commandment of God, that ye may keep your own tradition.34 By following their traditions instead of God’s commandments, the M ­ ississippi Christians perform heinous crimes while wearing the badge of Christianity. Thus, they transform Christ the Crucified into Christ the Crucifier. But, as Huck notes early on, his community never meant any harm by its actions.35 Surely Huck’s community meant no harm in discriminating against the blacks. Miss Watson meant no harm in going back on her word and deciding to sell Jim. The Shepherdsons meant no harm in murdering two Grangerford youths. And these Christians simply go on as if no harm was done. Such was Twain’s diagnosis of the corruptions of American Christianity: by appropriating Christian commandments, Mississippi Christians ostracize Christ from Christianity. The Black Christ In contrast to the Mississippi Christians, Twain introduces Jim as the ­ultimate Christian ideal. Jim’s actions prove more Christlike and less biased than any others’. This becomes evident early on by comparing the community’s efforts to rescue Huck with Jim’s efforts. Huck’s community goes through the exhausting efforts of boarding a steamboat for a single 51 Americana search down the banks of the river and then endures the painstaking task of posting a two hundred dollar reward, which was one hundred dollars less than the reward for Jim—but then again, young white boys were not selling for as much as runaway slaves.z36 In contrast, Jim explains his efforts to find Huck during the heavy fog:37 When I got all wor out wid wor, en wid de callin’ for you, en went to sleep, my heart wuz mos’ broke bekase you wuz los’, en I didn’ k’yer no mo’ what become er me en de raf ’. En when I wake up en fine you back agin’, all safe en soun’, de tears come en I could a got down on my knees en kiss’ yo’ foot I’s so thankful. Jim exhausts himself searching for his new companion to the point of total self-disregard. From this point on, Jim commits himself to protecting Huck without monetary reward, despite Huck’s fluctuating loyalty. Jim covers the dead man they encounter in the toppled house from Huck’s innocent eyes38; he gives Huck his old coat to sit on when Huck paddles ashore39; he gives Huck the more comfortable bed to sleep on40; he even often covers Huck’s night-watch shifts without complaint.41 Unlike Miss Watson, Pap, and other members of Huck’s community, Jim has no ­hidden motives in protecting Huck. He does not want to civilize Huck or to benefit from his fortune. He only wants a companion, a friend. Jim displays his love like no other character Twain presents. He does not dilute his love with hidden motives; he loves Huck as a sincere friend. This is shown by Jim’s similar reactions after each time he and Huck become separated: “­Goodness gracious, is dat you, Huck . . . It’s too good for true, honey, it’s too good for true. Lemme look at you, chile, lemme feel o’ you . . . thanks to goodness.”42 Jim loved his neighbor as himself. Recognizing the depth of Jim’s love, Huck finally concludes, “He was a mighty good nigger, Jim was.”43 Huck recognizes that Jim’s love proved more sincere than any of the Mississippi Christians’. In contrast to the Mississippi Christians’, Jim’s love for others also leads him to repentance, not redefinition. At one point, Jim displays this repentant nature to Huck: What makes me feel so bad dis time, ‘ uz bekase I hear sumpn over yonder on de bank like a whack, er a slam . . .en it mine me er de time I treat my little ‘Lizabeth so ornery . . .One day she was a-stannin’ aroun’, en I says to her, I says: ‘Shet de do.’ She never done it; jis’ stood dar, kiner smilin’ up at me. It make me mad . . .I fetch’ her a slap side de head dat sont her a-srawlin. My, but I wuz mad, I was agwyne for de childe, but jis’ den . . .’long come de wind en slam it to, behine de chile, ker-blam!—en my lan’, de chile never move! . . . She never budge! Oh, Huck, I bust out a-cryin’ en grab her up in my arms, en say ‘Oh, de po’ little thing!44 52 Americana Unlike the surrounding Christian culture, Jim does not excuse his actions toward his daughter. Instead, he takes responsibility for his actions and seeks to correct them; he takes his Elisabeth into his arms and prays for forgiveness and continues to punish himself for his actions. He did not alter a law or seek to convince himself of his patriarchal right to strike his daughter. He sobs in godly sorrow. Twain presents Jim as the ideal Christian, the incarnation of core Christianity. Twain’s characterization of Jim mirrors Christ’s timeless ­ ­lesson to His apostles: “He that is greatest among you shall be your servant. And whosoever shall exalt himself shall be abased; and he that shall humble himself shall be exalted.”45 Jim is the lowest, the servant, but through his actions, he becomes the greatest. Do Jim’s actions seem unintelligent, ungrateful, emotionless, or dishonest, as the Mississippi Christians had labeled him? Is Jim Christian? Jim’s selflessness serves as a contrast to the Mississippi Christians, and with time, it rubs off on Huck. Huck’s Subconscious Crusade Huck’s coming to conscience, his becoming like Jim, constructs Twain’s prescription for curing American Christianity. Through righting his wrongs, analyzing his feelings, and learning to evaluate his actions accordingly, Huck develops the Christlike attributes so scarce in American ­Christianity. Huck begins as a careless, selfish desperado. As an example, as Jim cries with joy after their initial separation in the fog, Huck pulls a prank; however, he lacks an audience. This lack of laughter ignites the first spark in Huck’s leap over the social hurdle of selfishness to seek forgiveness. Huck relates, “It made me feel so mean I could almost kissed his [Jim’s] foot to get him to take it back.” Then, recounting the height of the social hurdles set before him, Huck continues, “It was fifteen minutes before I could work myself up to go and humble myself to a nigger—but I done it, and I warn’t ever sorry for it afterwards, neither.”46 Here, like Jim, Huck accepts responsibility for his actions instead of excusing them. Thus, Huck takes his two first steps in overcoming his instilled indifference; he rights his wrongs and analyzes his feelings. By analyzing how he feels, Huck begins to overcome the condemning, communal conscience in order to awaken his own conscience—a struggle that constitutes his greatest trials. For example, as he realizes the illegality of 53 Americana his desire to help free Jim, Huck explains, “Conscience says to me, ‘What had poor Miss Watson done to you, that you could see her nigger go off right under your eyes and never say one single word?’” Then Huck echoes a communal reproach he must have heard often repeated: “‘What did that poor old woman do to you . . . Why, she tried to learn you your book, she tried to learn you your manners, she tried to be good to you every way she knowed how?’”47 The indoctrination of Huck’s community plagues his conscience to the point of self-condemnation for keeping the second highest commandment: loving his neighbor as himself. However, Huck decides against conscience—those ingrained traditions and teachings he assumes as his conscience—and sacrifices his own safety in order to remain loyal to Jim. Huck’s loyalty to Jim instead of to cultural traditions provides the first step in Twain’s cure for American Christianity; Huck evaluates the consequences of his actions according to how his actions make him feel. Realizing that further harboring Jim causes him no instant grief, Huck reflects, “Then I thought a minute, and says to myself, hold on,—s’pose you’d a done right and give Jim up; would you felt better than what you do now?” Then without hesitation he answers, “No, says I, I’d feel bad.”48 Huck realizes that what he has always learned to be proper is not necessarily so—at least it is not what makes him feel best inside. With each repeated evaluation of his actions, Huck begins to resurrect his inherent, individual conscience that Mississippi Christianity had so actively numbed. Twain illustrates Huck’s resurrection of conscience as Huck expresses his disgust of the malice he witnesses between the Grangerfords and ­Shepherdsons. Huck admits, “I wished I hadn’t ever come ashore that night, to see such things. I ain’t ever going to get shut of them—lots of times I dream about them.”49 Because Huck has become an outsider with Jim—his Christlike friend—he is able to recognize his community’s hypocrisy and fight against it. Jim’s Christlike friendship heals Huck’s blindness and he can now see the Mississippi Christians’ twisted doctrines and their fatal consequences. Renowned American novelist, F. Scott Fitzgerald, explains the significance of Huck’s new-gained perspective: “Huckleberry Finn took the first journey back. . . . His eyes were the first eyes that ever looked at us [America] objectively that were not eyes from overseas. . . . He wanted to find out about men and how they lived together.”50 As Fitzgerald 54 Americana explains, Huck’s objectivity allows him to recognize the flaws of American ­Christianity and its modern crucifixion of Christ. As Huck returns from the Grangerfords to Jim and the raft, he compares his rediscovered bliss with the sickening experiences ashore. His rediscovery provides Twain’s overlying Christian ideal: “For what you want, above all things . . . is for everybody to be satisfied, and feel right and kind towards the others.”51 This is the essence of Christianity: “to love thy neighbor as thyself.” Although Huck recognizes the bliss of achieving this Christian ideal, he often falters, slipping into the Duke and King’s temptations. His faltering displays the difficulty for individuals to completely break free from cultural conformities even after they recognize their faults. But again, Huck remembers to evaluate the consequences of his actions. After duping Mary Jane, he recognizes the guilty feeling too often suppressed by the Mississippi Christians and commits himself to right his wrongs instead of excusing them. Huck explains, “I felt so ornery and low down and mean, that I says to myself, My mind’s made up; I’ll hive that money for them or bust.”52 Huck recognizes his guilt and again fixes his mistakes Huck realizes that it takes a true Christian—as witnessed earlier in Jim as he mourns the mistreatment of his deaf daughter—to feel sorrow enough to repent. Huck presents his final plea of repentance through a seemingly unchristian declaration of commitment. Through this plea, Twain constructs Huck’s epic escape from the false Christianity rooted in the American Christian culture. After writing his confessionary letter to Miss Watson, in which he plans to turn his back on Jim once and for all, Huck explains, “I studied a minute . . . and then says to myself: ‘All right, then, I’ll go to hell’—and tore it up.”53 As unChristian as it may seem to willingly go to hell, Huck’s resolve to be damned before betraying Jim reveals the depth of Huck’s Christlike love for his friend. Here Huck embodies the ultimate Christian characteristic: “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.”54 At this point, when Huck is willing to give up his life for Jim, Huck completes his crusade from selfishness to selflessness. Through righting his wrongs, analyzing his feelings, and evaluating the consequences of his actions, Huck develops the Christlike love so scarce in American Christianity. Despite his youthful flaws, Huck learns to love others more than himself: a virtue still endangered in contemporary Christianity. 55 Americana Modern American Christianity The blind obedience, labeling, and redefining of Christian doctrine throughout Huckleberry Finn has continued amongst American Christian communities Modern American Christian communities also make the mistake of assuming personal purity. Attacking Twain publicly, famous ­American novelist Louise May Alcott exclaimed, “If Mr. Clemens [Mark Twain] cannot think of something better to tell our pure-minded lads and lasses he had best stop writing for them.”55 Probably offended by Twain’s natural use of the then accepted term of nigger, as well as by Huck’s youthful follies, Alcott, a proclaimed Christian, undermines Twain’s overt ­Christian theme of developing Christlike love. To Christian communities, what could be more important to teach their pure-minded youth than to “love thy neighbour as thyself,” as Huck learned to love Jim? Yet, Christian communities from Twain’s time through today remain vexed by Twain’s choice of prose, blinding them to the bigger picture that Huckleberry Finn presents. Although legalized slavery in the United States is a thing of the past, similar episodes of dehumanizing contempt towards other races, opposite genders, and other minorities continues throughout the United States, often amidst acclaimed Christian communities. This suggests that many modern American Christians continue to follow cultural traditions similar to the traditions Huck so inspiringly transcends. Like Huck’s community, many modern American Christians present themselves as saints by condemning minute evils—Huck’s uncivilized hobbies—while overlooking their own moral monstrosities. Such hypocrisy makes it difficult to discern between Christ and Christianity. In Huckleberry Finn, Twain seems to warn that Christianity has, in many cases, become a culture of traditions that have strayed, in one form or another, from the biblical teachings of Christ. As witnessed by Huck, many Christian communities have redefined doctrines and given their beliefs mere lip service while they continue conforming to the world’s ever-changing trends. This devolution of Christianity makes it difficult to discern between beliefs and behaviors. Through Huck, Twain motivates his readers to measure their actions against their verbal beliefs. He invites individuals to reevaluate their beliefs and practices—to consider their neighbors’ needs instead of justifying their search for solitary satisfaction. By viewing Twain’s text with an understanding of the Mississippi Christians’ 56 Americana misuse of Christianity, Huck becomes a Christian literary hero, reminding the masses to practice what they preach and to become certain that what they preach agrees with Christ, whom they claim to follow. If Christian communities do not reevaluate their sometimes blinding traditions, they will continue straight ahead, following the contradicting interpretations and redefinitions of scripture as a culture of Tom Sawyers condemning the societal Hucks. They will continue complicating their neighbors’ lives in their best attempts to “set a free nigger free”56 instead of respecting their neighbors’ individuality, celebrating their uniqueness, and loving them despite their differences. Through Huckleberry Finn, Twain criticizes 1840s Mississippi Christianity in order to declare the ongoing need for American Christians to, like Huck, invite Christ back into Christianity by righting their wrongs, analyzing their feelings, and evaluating the consequences of their actions, thus developing Christlike love. 57 Americana Notes 1 “Samuel Langhorne Clemens,” Contemporary Authors Online, Gale Group, in USEM 27B Readings, Brandeis University, http://people.brandeis.edu/~teuber/twainbio.html. 2 Albert Bigelow Paine, Mark Twain: A Biography, vol. 1 (Middlesex: Echo Library, 2006), 1:700. 3 Mark Twain and Bernard A. De Voto, Letters from the Earth: Uncensored Writings (New York: Harper Collin, 2004), 237. 4 Mark Twain, Christian Science: With Notes Containing Corrections to Date (New York: Harper, 1907), 82. 5 Ron Powers, Mark Twain: A Life (New York: Simon and Shuster, 2004), 29. 6 Mark Twain, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Norton Anthology American Literature, vol. 2 (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2008), 107. 7Ibid. 8 Matt. 6:6 (King James Version). Subsequent biblical references also refer to the King James version. 9Twain, Huckleberry Finn, 58. 10 Mark 12:29–31. 11Twain, Huckleberry Finn, 102. 12 1 Sam 16:7. 13Twain, Huckleberry Finn, 205. 14 Matt. 23:27–28. 15Twain, Huckleberry Finn, 147. 16 Ibid., 163. 17 Ibid., 204. 18 Ibid., 218 19 Matt 7:1. 20Twain, Huckleberry Finn, 135. 21 Ex. 20:16. 22Twain, Huckleberry Finn, 127.z 23 Ex. 20:15). 24Twain, Huckleberry Finn, 163. 25 Ex. 20:13. 26Twain, Huckleberry Finn, 107. 27 Ibid., 179. 28 Ibid., 176. 29 Matt 23:23–24. 30Twain, Huckleberry Finn, 170. 31 Ibid., 176. 58 Americana 32 Ibid., 189. 33 Ibid., 173. 34 Mark 7:6–9. 35Twain, Huckleberry Finn, 111. 36 Ibid., 124, 135. 37 Ibid., 153. 38 Ibid., 131. 39 Ibid., 163. 40 Ibid., 186. 41 Ibid., 187, 204. 42 Ibid., 151. 43 Ibid., 204. 44 Ibid., 204–205 45 Matt 23:11–12. 46Twain, Huckleberry Finn, 153. 47 Ibid., 162. 48 Ibid., 164–165. 49 Ibid., 179. 50 Esther Lombardi, “Huckleberry Finn—What Have Writers Said About Huckleberry Finn?” About.com Classic Literature, http://classiclit.about.com/od/adventuresof huckleberry/a/huckfinn_writer.htm. 51 Twain, Huckleberry Finn, 185. 52 Ibid., 216. 53 Ibid., 239. 55 “Banned Books: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” Time, 29 September 2008, http://www. time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,1842832_1842838_1844945,00.html. 56Twain, Huckleberry Finn, 285. 59