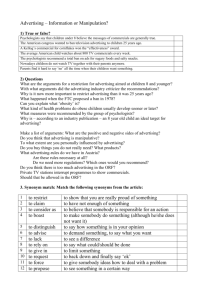

Liquormart, Inc v Rhode Island

advertisement