as a PDF

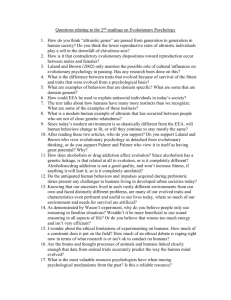

advertisement

Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology www.jsecjournal.com – 2008, 2 (2): 69-73. Book Review LOOKING THROUGH THE EVOLUTIONARY LENS: CONSUMER BEHAVIOR AND EVOLUTIONARY PSYCHOLOGY Michael Camargo State University of New York, New Paltz Kelly L. Donahue State University of New York, New Paltz The Evolutionary Bases of Consumption. By Gad Saad. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah, New Jersey, 2007; ISBN: 080585150X In his book, The Evolutionary Bases of Consumption, Gad Saad has done for consumer research what many other scholars have done for other disciplines (e.g., Gottschall & Wilson, 2006; Jones & Goldsmith, 2005; Nesse & Williams, 1996). This book provides yet another example of the importance and utility of evolutionary psychology (EP) in an area currently void of any evolutionary theory. Throughout the book, Saad presents research on consumer behavior and views it through an evolutionary lens, illustrating parallels between different consumer behaviors, marketing strategies, and our evolved human nature. At the same time, he challenges the social constructionist view that all human behavior is learned through socialization and suggests that our behavior may be, at least in part, affected by our evolved human nature. Throughout, he suggests that EP can aid consumer research by predicting when a researcher might expect to find evolved similarities versus learned differences in consumers in all parts of the world. Saad takes a similar approach to that of Carroll (2005) by applying what McGuire and Troisi (1998) labeled behavior systems (functional and causally related patterns of behavior). Originally used to identify human behavioral patterns as a means of understanding mental disorders, Saad applied behavior systems to the identification of general themes in consumer marketing. The behavioral systems of focus are reproduction, survival, kin selection, and reciprocal altruism. He demonstrates the lack of evolutionarily informed hypotheses in the consumer research field, resulting in disconnected, unorganized findings and he graciously demonstrates the current ubiquity of evolutionary principles in the field of consumer research that has been unnoticed. The goal of this book is, “…to demonstrate that consumer behavior cannot be accurately understood, nor fully investigated without the necessary infusion of biological and Darwinian-based phenomena that have shaped our human nature (xvii).” In the first two chapters Saad provides a rich overview of the field of evolutionary psychology and consumer research, and discusses the current dependence on the Standard Social Science Model (SSSM) (Tooby & Cosmides, 1992) that underlies most consumer research. The SSSM posits that human behavior can be explained exclusively through culture and learning – that the blank-slate metaphor for the human mind need not be questioned. © 2008 Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology 69 Looking Through the Evolutionary Lens In his analysis, he suggests that the majority of consumer research to date has focused on domain-general, proximate-level theorizing, thus largely ignoring evolutionary influences. He emphasizes this point by analyzing several main areas of interest to consumer researchers, including learning, motivation, culture, decision making, perception, attitude formation and change, emotions, and personality. He contends that humans and their behaviors are shaped just as much by their innate biology as by their surrounding environments and life experiences, and that incorporating evolutionary explanations into consumer research would further enhance the understanding of consumer phenomena. In a subsequent section on human consumption behavior, Saad proposes that the four Darwinian behavioral systems, or modules, of reproduction, survival, kin selection, and reciprocal altruism, more effectively explain the consumption patterns of humans than the SSSM does. Each of these modules can be viewed as a set of strategies that solved specific problems over our species’ phylogenetic history. The reproductive module solves recurring problems related to mate choice (e.g., the reproductive success of females is limited compared to males, and therefore females are less likely to be as promiscuous). The survival module solves problems related to individual survival in a specific environment (e.g., a fear of snakes). The kin selection module solves problems related to the survival of one’s genes in the subsequent generation, creating behavioral patterns that are expressed as altruism towards one’s kin. The reciprocal altruism module solves the problem of living in large, genetically unrelated groups, where cooperation among non-kin is necessary for individual survival. He begins his argument with a discussion of sex differences and contends that the social constructionist view is backwards, in that products and marketing ploys do not shape our understanding of the world. Rather, he argues, these products and marketing designs accurately reflect our evolved human nature. A compelling example provided is that of toy preferences. He reviews Berenbaum and Hines’ (1992) study of children’s’ sex-typed toy preferences from a sample of children diagnosed with congenital adrenal hyperplasia, a disorder that results in girls who have masculine traits and behaviors. The study found that the girls with this disorder had an increased preference for stereotypical masculine toys. This result was found despite the parents’ attempts at socialization. An evolutionary account of this phenomenon suggests that males and females prefer specific toy designs (i.e., males prefer motion; females prefer form and color) because the presence or lack of androgen predisposes the visual system to attend to specific objects in the environment. This sex-specific attention bias enables male children to practice skills related to hunting and female children to practice skills related to foraging and the caring of infants, thus increasing their reproductive success (Alexander, 2003). He also discusses the reliance of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs by those in the consumer research field, and views conspicuous consumption, the spending of money on goods and leisure activities that serve to advertise one’s wealth and status (Veblen, 1899), as flying in the face of this theory. Saad points out that while Maslow’s hierarchy makes sense intuitively, it does not explain the occurrence of poor people spending money on status-related items. He suggests that conspicuous consumption can be viewed as a handicap used to signal one’s social status. Saad then goes on to demonstrate how a majority of advertising and media content focuses on masculinity and femininity from a social constructionist perspective. He argues that instead of focusing on culture-specific cues, more universal applications Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology – ISSN 1933-5377 – Volume 2 (2) 2008. 70 Looking Through the Evolutionary Lens can be identified and thus applied by using an evolutionary framework that identifies sexspecific mating preferences. He demonstrates this idea by pointing out that many advertisement slogans already cater to at least one of the four Darwinian modules. Advertisement slogans that address an individual’s looks (e.g., the Vichy Skin Care slogan, “Health is vital. Start with healthy looking skin.”) play into an evolved strategy to use biological traits (in this case healthy looking skin) as an assessment of mate value (the reproductive module). Other slogans, such as Sprite’s “Obey your thirst,” Jif peanut butter’s “Choosy mothers choose Jif,” and State Farm Insurance’s “Like a good neighbor, State Farm is there,” map onto the survival, kin selection, and reciprocal altruism modules, respectively. Saad argues that these slogans are so successful because they play directly into our evolved strategies that have increased the survival and reproductive success of our ancestors throughout our species’ evolutionary history. Saad then attempts to illustrate the role evolution plays in the formation of culture. He provides an overview of many of the most popular forms of cultural expression, mainly television shows, music themes, religion, self-help books, music videos, and literature and discusses the currently accepted explanations for these (mainly that they create culture). He contends that all of these forms of cultural expression contain within them reference to at least one of the four Darwinian modules, and exist in their current form because they are accurate depictions of human existence, making them plausible and, more importantly, marketable to the consumer. For example, the sitcom 8 Rules for Dating my Teenage Daughter concerns a father who is constantly struggling to protect his daughter from potential male suitors. Saad argues that the premise of this show is successful because it plays into a specific aspect of human mating psychology, and that a show titled, 8 Rules for Dating my Teenage Son, would be evolutionarily irrelevant, making it less plausible and less marketable. He also explores the Darwinian etiologies of the seven deadly sins, suggesting that sloth, envy, gluttony, lust, pride, revenge, and greed are universal human weaknesses, which manifest themselves mainly due to a mismatch between the current environment and that of the Pleistocene. “Mismatch Theory” argues that organisms have an evolved set of behavioral and emotional strategies (or behavioral patterns), preserved by natural selection, that increased an individual’s reproductive success in the specific environment where these strategies evolved, but no longer provide the same benefit in the current environment. He contends that the “Seven Deadly Sins” are expressed through numerous acts of sexspecific “dark-side” consumption behaviors, including pornographic addictions, compulsive buying, eating disorders, and pathological gambling. He again demonstrates problems associated with the SSSM’s attempt to explain these phenomena and suggests that more ultimate, domain-specific, evolutionary theorizing would assist researchers in identifying the forces that can predispose individuals to succumb to such “dark-side” consumption acts. One criticism of this book is that Saad has tackled two very large problems, mainly the benefit of applying EP principles to current consumer behavior research, as well as the role of our evolutionary lineage in shaping our current behaviors, in a scant 276 pages. Although both of these topics are undoubtedly related to one another, a lot of information and novel ideas have been densely packed together. Obviously this criticism is more the result of a compromise between publisher and author, as opposed to a lack of knowledge on the topic, however, certain aspects of this book could have been immensely enhanced by a more thorough discussion. For example, a closer look Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology – ISSN 1933-5377 – Volume 2 (2) 2008. 71 Looking Through the Evolutionary Lens “Mismatch Theory” and the differences between our current environment and the Pleistocene that may place some “dark-side” consumption behaviors in a more logical light. Furthermore, the topics of black-market consumption, as well as the consumption of leisure are never addressed. Do these types of consumption behaviors map just as easily onto the four Darwinian modules as the other types of consumption behaviors that have been presented? Are there other types of consumer behavior that do not seem to have a Darwinian etiology? A look at these other types of consumption behaviors may have further strengthened Saad’s argument. Saad concludes his thesis by showing how EP can enrich consumer behavior research. He suggests that one of the main benefits of taking a Darwinian perspective to consumer research would be to permit researchers to address scientific issues at both proximate and ultimate levels. He also suggests that a Darwinian perspective would permit consumer researchers to recognize the importance of both domain-general and domain-specific mental modules and theorizing. The SSSM sees the mind as an accumulation of general-purpose, domain-independent mental processes and algorithms, as demonstrated by behaviorism, various cognitive approaches, and the “cost-benefit” framework. In contrast, EP views the mind as consisting of Darwinian modules that have each evolved to solve very specific survival problems. Thus, the process that the mind uses to solve one adaptive problem is not necessarily the same process that would be used to solve a different one. Unlike the ideas proposed by domain-general theorizing, the processes that the mind uses to solve a specific problem are not necessarily transferrable to other domains. Currently, most consumer researchers use domain-general theorizing, producing vast amounts of unconnected findings, and would be greatly supplemented by the application of domain-specific theorizing. Throughout the book, Saad illustrates the vast field of knowledge currently untapped by consumer researcher and provides the means by which EP can be used to understand consumer behavior. In doing so, he has provided the field of consumer research with a new, more unifying perspective to work from and has made a strong case for the importance of EP in understanding consumer behavior. At the same time, he has also addressed one of the most salient debates of our time; what determines human behavior, our evolved human nature or socialization? He concludes that either theory on its own cannot adequately explain the myriad of human consumption behaviors, and only an overarching framework that incorporates both evolutionary theorizing and culturally learned behaviors can address the countless behaviors that make us human. Received April 7, 2008; Revision Received April 30, 2008; Accepted May 5, 2008. References Alexander, G.M. (2003). An evolutionary perspective of sex-typed toy preferences: Pink, blue, and the brain. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32, 7-14. Berenbaum, S.A., & Hines, M. (1992). Early androgens are related to childhood sextyped toy preferences. Psychological Science, 3, 203-206. Carroll, J. (2005). Literature and evolutionary psychology. In D. Buss (Ed.), The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology (pp. 931-952). New York: Wiley. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology – ISSN 1933-5377 – Volume 2 (2) 2008. 72 Looking Through the Evolutionary Lens Gottschall, J., & Wilson, D.S. (Eds.) (2006). The Literary Animal: Evolution and the Nature of Narrative. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press. Jones O.D., & Goldsmith T.H. (2005). Law and behavioral biology. Columbia Law Review, 105, 405-502. McGuire, M., & Troisi, A. (1998). Darwinian Psychiatry. New York: Oxford University Press. Nesse, R.M., & Williams, G.C. (1996). Why We Get Sick: The New Science of Darwinian Medicine. New York: Vantage Books. Saad, G. (2007). The Evolutionary Bases of Consumption. Mahwah, New Jersey: Erlbaum. Tooby J., & Cosmides L. (1992). The psychological foundations of culture. In J.H. Barkow, L. Cosmides, & J. Tooby (Eds.), The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture (pp. 19-136). New York: Oxford University Press. Veblen T. (1899). The Theory of the Leisure Class. New York: MacMillan. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology – ISSN 1933-5377 – Volume 2 (2) 2008. 73