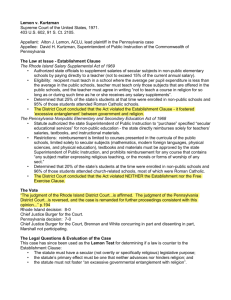

State Aid to Students in Religiously Affiliated Schools: Agostini v

advertisement