Student Religious Organizations - Washington State Board for

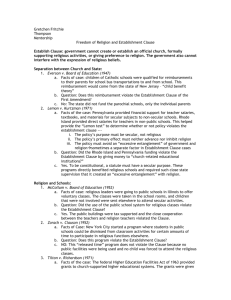

advertisement

Student Religious Organizations CUSP 2014 Fall Meeting October 23, 2014 By John Clark Assistant Attorney General First Amendment Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances. Healy v. James, 408 U.S. 169 (1972) Facts: Student group loosely affiliated with national organization that advocated political change through violence requested recognition as a student organization. President denied recognition because of ideals of national organization. Club was unable to meet on campus or to advertise to the campus community. First Amendment includes freedom to associate. Individuals have a right to associate to further their personal beliefs. • Denial of association’s recognition prohibited it from meeting as a group, using college facilities to meeting, advertising on bulletin boards or in college newspaper. • College improperly placed burden on association to show that it could comply with college’s rules and was a form of prior restraint. • College is free to deny recognition to activities that violate reasonable campus rules or substantially interfere with the opportunity of other students to obtain an education. Article I, Section 11 No public money or property shall be appropriated for or applied to any religious worship, exercise or instruction, or to the support of any religious establishment. Widmar v. Vincent, 454 U.S. 263 (1981) Facts: University created a forum for student organizations by accommodating their meetings. University denied recognition to a student group that wanted use of University facilities for religious worship and discussion. The University’s policy of granting access to facilities created a limited public forum. Any restriction based on religious content must meet a narrowly tailored, compelling need. Establishment Clause does not prohibit viewpoint neutral, equal access to state facilities, since the primary effect of the policy neither advances nor inhibits religion. State Establishment Clause could never contravene the First Amendment (stated without reaching the Supremacy Clause). Potential Violation of State’s Establishment Clause is not a compelling need Mergens v. Westside Comm. Schools, 496 U.S. 226 (1990) Facts: Christian club challenged school’s denial of recognition to use facilities after hours under the Equal Access Act. The School claimed that providing a school advisor to supervise the club would violate the Establishment Clause. The Court rejected the state-sponsorship of religion argument because the Act only provided a school employee to attend the meeting for custodial purposes. “Closer question” if paid employee advisor actively participated in religious rights with the students. Malyon v. Pierce Cy., 131 Wn.2d 779 (1997) (volunteer chaplains). Lamb’s Chapel, 508 U.S. 384 (1993) Facts: N.Y. statute allowed schools to adopt reasonable regulations to allow afterhours use of school facilities for social, civic, and recreational meetings. Church requested use of facilities to publicly show a film series dealing with family and child-rearing issues faced by parents from a religious perspective. School opened limited forum by authorizing afterhours use of its facilities. Prohibition of child-rearing film from a religious perspective violated the church’s free speech because it amounted to viewpoint discrimination. Rosenberger v. Univ. of Virginia, 515 U.S. 819 (1995) Facts: The University recognized 15 student news organizations. Student organization applied for funding to publish a religiously oriented newspaper at the University. The University denied funding because funding was not available for religious activities. Having chosen to provide funding to student groups and newspapers, the University could not withhold funding based on the religious viewpoint of one of the organizations. Funding religious based organizations does not violate the Establishment Clause when the government applies neutral criteria and evenhanded policies. University of Wisconsin v. Southworth, 529 U.S. 217 (2000) Facts: Students sued University requesting the ability to opt out of funding student political or ideological organizations offensive to their personal beliefs. They alleged that the mandatory collection of S&A fees violated their rights to free speech, free association, and free exercise. Mandatory payment of S&A fees to fund student organizations and programs is permissible if the program or activity is viewpoint neutral. Good News Club v. Milford Central Sch., 533 U.S. 98 (2001) Facts: School allowed afterhours use of facilities for events pertaining to the welfare of the community. Parents applied to use school facilities after hours to provide bible study, sing songs, and teach morals. School denied usage as tantamount to religious instruction. School engaged in viewpoint discrimination. Purely private religious use in a limited public forum does not violate the Establishment Clause. Locke v. Davey, 540 U.S. 712 (2004) Facts: Washington offers high achieving students a promise scholarship that can be used for tuition so long as the student certifies that he/she is not pursuing a degree in devotional theology. Denial of subsidy does not implicate free speech. Rule does not evince a hostility toward religion like in the Church of Lukumi Babalu Aye, but merely indicates the state’s preference not to fund this religious endeavor. There is “play in the joints” between the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise clause – the state can choose to fund the scholarship or not without violating the First Amendment. Christian Legal Society (Hastings) v. Martinez, 561 U.S. 661 (2010) Facts: Student religious organization filed suit against Hastings for requiring it to comply with the College’s nondiscrimination policy. The policy required that all student organizations be open to anyone in the student body. Policy that all recognized student groups must be open to all students was a reasonable and viewpoint neutral policy. The policy set the parameters of the limited forum. For instance, schools can limit student groups to students only. The group’s freedom not to associate was co-extensive with its free speech rights in the limited public forum. Adequate alternative forums were available for the group if it chose not to accept the University’s funding.