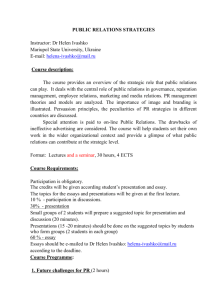

Identity, Image, Reputation, and Corporate Advertising

advertisement