Does it pass the sniff test?

advertisement

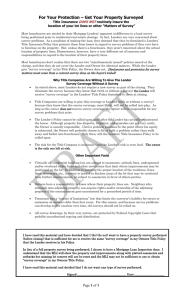

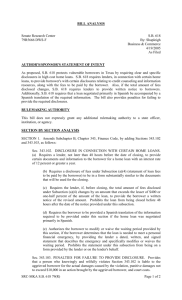

NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2004 “Does it pass the sniff test?” Asset-based lenders ask this question when presented with a prospective borrower, aware that it is not always easy to sniff out trouble that may lie hidden beneath the surface of a company’s financial statements. Indeed, it takes experience and judgment to assess that information and to sense whether the business activities behind them bear further scrutiny. This makes comprehensive due diligence an essential element of the lender’s enterprise, perhaps even the surest antidote to disaster. But due diligence doesn’t mean simply accepting the reports provided by the borrower and its auditor as sufficient without extensive double checking. Although lenders look to inventory and accounts receivable as security for their loans, they commonly rely on the borrower’s auditing firm to confirm the existence of these assets and assess their value, without engaging in extensive due diligence on their own. Why shouldn’t they? The auditors say they have applied generally accepted auditing standards in conducting their audit – standards requiring the auditors to obtain reasonable assurance that the financials are free of material misstatement, whether caused by error or fraud. Fraud artists know that lenders rely on audited financials. They also know that this limits the effectiveness of lenders’ due diligence. And they take full advantage of this situation. We have investigated recent scams with ultimate losses ranging between $10 and $150 million involving public and private companies. All were accompanied by audited financial statements. The perpetrators created and reported fictitious inventories and accounts receivable. The inventories turned out to be valueless, or they existed only as computerized bookkeeping entries superimposed on real activities. The accounts receivable were conditional or contingent sales or transactions recorded by members of management to bolster collateral reports or cash flows. The scams were so sophisticated that they fooled lenders into thinking that the enterprises in question were far bigger and healthier than they actually were. And no wonder. The lenders in question relied on the outside auditors, and the outside auditors relied on management. Do you see a pattern developing here? For any deal to pass the sniff test, lenders should understand the audit process in detail. They owe it to by Jeffrey E. Brandlin themselves to know whether, and to what extent, the company’s auditors applied specific auditing procedures. Did the auditors support their report with competent evidential matter obtained from third parties? Or did they rely almost solely on management representations, company records, and so on? This is a common theme in many frauds, to the great regret of the lenders involved. In a study, “Top 10 Audit Deficiencies,” published in the AICPA’s Journal of Accountancy in September 2002, the authors, Mark S. Beasley, Joseph Carcello and Dana R. Hermanson, discovered that among SEC enforcement actions against auditors in the period 1987 to 1997: “The most common problem, in 80 percent of the cases, was the auditor’s failure to gather sufficient audit evidence. Many of the cases involved inadequate evidence in areas such as asset valuation, asset ownership and management representations. In almost half of the enforcement actions, the SEC alleged the auditors failed to apply GAAP pronouncements or applied them incorrectly.” Copyrighted material. For website posting only. Reproduction or bulk printing prohibited. The cases involved public companies, and the lesson is clear: Lenders should not assume that audited financials will give them a true picture of their borrower’s financial position, results of operations and cash flows. They should be doubly skeptical of audits done on privately held companies without SEC oversight. The lender’s first line of defense is to put the auditing firm on notice that it is relying on the information in the audit in deciding whether to advance credit to the borrower. This can be accomplished by asking the auditing firm to sign a letter acknowledging its awareness that the lender is relying on its work to decide whether to extend credit. Or the lender can send copies of the borrower’s financial statements to the auditor asking whether they are the statements the auditor certified and requesting the auditor to advise if this is not the case. Either way, the goal is to put the auditor on notice that, should a borrower fall into trouble, the lender does not intend to absorb the loss on its own. Note, however, that this strategy merely provides the lender with an umbrella in case of a downpour. The better idea is not to go out into the rain in the first place. Lenders should focus their due diligence on filling in the gaps exposed by the question, “What procedures did the auditing firm follow in verifying the numbers on the financial statements that represent inventory and receivables?” Assume, for example, that a borrower has $100 million in inventory and that the auditor verified the existence of half by physical inspection and, finding nothing out of line with the numbers offered by management, inferred that the remaining, uninspected half would comport with management’s numbers. Such procedures may or may not set alarm bells ringing, depending on a lender’s appetite for risk and its confidence in the honesty of the borrower. If the lender finds that the auditors really know the composition of the borrower’s inventory and not just the overall performance characteristics, it’s a good sign. To that end, lenders should determine what observation procedures the auditors followed and how much of inventory they covered. Most readers of financial statements assume that outside auditors participate in inventory observations covering inventory in its entirety. This is a dangerous assumption. In one case, the certifying accountants participated in none of the borrower’s inventory procedures, choosing instead to rely on the work of “other auditors.” In another case, the auditors participated in checking only half of the inventory. In yet another case involving a perishable foods distributor, the auditor’s work papers listed items purchased one or two years prior to the audit. As a lender, would you want to know this before or after you funded a loan to such a borrower? Lenders must also know whether the auditors have done adequate detailed testing of inventory values, salability, obsolescence, and the like. Do the auditors know which SKUs sell fast and which sell slowly? Is their audit evidence generated internally or externally? The same evaluation is necessary when considering accounts receivable. Did the auditors confirm accounts receivable? If not, why not? Did they confirm transactions or balances? If transactions, did they present all transactions comprising the balance for confirmation, or at least significant transactions comprising a significant part of the balance? Or did they subject only a small percentage of transactions to confirmation? What were the results of the confirmation circularization? Are those results reliable? Are they adequate? Do they confirm payment terms? How did the auditors satisfy themselves that sales were not conditional or contingent? Irrespective of the scope and results of the confirmation testing, it is not a good sign if the auditors did not inspect the actual remittance advices representing subsequent cash receipts. The testing of subsequent cash receipts should not be perfunctory; coverage should be substantial. Absent adequate and appropriate testing, how can the auditors satisfy you that the balances are properly valued and that the balances are collectible? These are simple questions, but because the answers may affect the decision whether to extend credit, they demand good oldfashioned pick-and-shovel audit work. See “A Lender’s Checklist" Shallow auditing can also hide sloppy accounting with a similar impact on the borrower’s position even when there is no intent to defraud. In another case, the borrower exchanged overhauled industrial equipment for its customers’ expended equipment. The borrower reconditioned the expended equipment, charging its customers the cost to overhaul the items plus a service fee. In essence, the borrower was trading items in and out of its inventory, There was no apparent fraudulent intent here, just sloppy accounting procedures and an auditor who didn’t dig into them. Taken together, this enabled the borrower to show its lenders a value for inventory that didn’t come close to reality. Unfortunately, failures like these happen, making it all the more necessary for lenders to understand the audit process. Lenders must also evaluate the adequacy of their own standard due-diligence procedures in light of the shortfalls of the audit process, embellishing and tailoring those procedures to fit the particular credit facility under consideration. Skepticism is the lender’s most valuable virtue, and it should extend beyond what a borrower says about its prospects to what the borrower’s accounting firm does or does not say about the borrower’s financial position, results of operations and cash flows. There is no substitute for good due diligence, and sometimes the most reliable due diligence is what lenders do on their own. ▲ typically taking in an item from a customer for reconditioning and sending the customer the identical part, already reconditioned, from inventory. The borrower properly recognized the cost to overhaul the equipment and capitalized these costs in inventory, but it failed to relieve inventory for reconditioned equipment sent to the customer. Jeffrey E. Brandlin, CPA, is president of Brandlin & Associates, Los Angeles, CA. He may be reached at jeff@brandlin.com, or 310-789-1777. Investigative Accounting & Consulting 1801 Century Park East, Suite 1040 Los Angeles, California 90067 (310)789-1777 www.brandlin.com Reprinted from The Secured Lender, November/December, 2004 by The Reprint Dept., 800-259-0470; Part #9567-1204 S ome of the items on the following checklist require more work than others. Some, in addition, may seem so elementary as to invite the lender to take them for granted. In fact, the items on this list are crucial, and the lender who ignores them invites trouble sooner or later. Background checks of: ➤ Company principals ➤ Related parties operating companies doing business with borrower ➤ Principals of important suppliers and/or customers Finance Department ➤ CFO/controller Education Technical skills Independence from undue pressure from company principals Reputation among past lenders Promptness and openness in supplying company data to lender ➤ Back Office Procedures Strength and adequacy of internal controls Segregation of duties Integrity and safety of accounting records, including password/firewall protections Procedures for backup of accounting records Access to such data ➤ Cash Procedures for establishing new bank accounts Control over and location of domestic and foreign bank accounts Control over wire transfers Confirmation of bank statements Confirmation of interim balances Adequacy of monitoring procedures for unusual activity in cash accounts at lenders institution ➤ Accounts Payable Concentration Turnover Aging Credit terms ➤ Accounts Receivable Borrowing base audit Concentration of risk Aging trends with emphasis on turnover Stated credit terms Favored-customer credit terms Credit memo accounting recognition procedures Unapplied cash transactions and accounting procedures Policy for determining reserve for bad debts Historical AR write-offs Monthly adjustments to aging report ➤ Inventory Borrowing base audit Existence and location of product Aging Control of inventory Policy for determining obsolete or slowmoving product Frequency of product transfers among company locations and effect on inventory aging report when this happens Consistency of allocations in inventory valuation for: Material Direct labor Manufacturing overhead IT Department ➤ Education and technical skills of director ➤ Independence from undue pressure from company principals ➤ Degree of control over company hardware and software