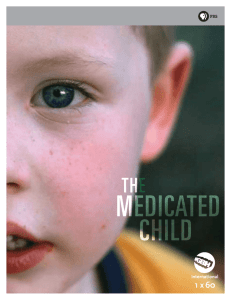

Medication & Childhood Mental Disorders

advertisement

Gorson 1 Liz Gorson English 124 March 14, 2011 Medication & Childhood Mental Disorders Choices govern our daily lives. We make selections regarding our eating habits, clothing, and sleeping patterns. Other choices are more difficult, such as delving into an unfamiliar situation or acknowledging a mistake. There are also instances when others decide our paths, particularly in childhood. Parents have a responsibility to make the appropriate choices concerning the welfare of their children. When deciding to medicate a child with symptoms of a mental disorder, this accountability becomes challenging. This uncertainty is often due to a lack of professional knowledge regarding the best solutions. The media often emphasize the “quick fix” resolution as giving children a pill—often multiple pills—to quiet their tantrums and stabilize their mood. However, in the majority of cases, the negative consequences of pharmacological treatment of children and adolescents outweigh the possible benefits. In recent years, there has been a surge of self-­‐help books, websites, and technologies aimed toward desperate parents of troubled children (The Medicated Child). Perhaps due to issues of convenience and income, these corrective measures are increasingly replacing empirically supported treatments as the first choice solution (The Medicated Child). British child psychiatrist Sami Timimi refers to this progression as the “Mcdonaldisation” of childhood mental health” (Paton). Timimi explains that similar to the fast food business, “the medical industry fed on peoples’ Gorson 2 desire for instant satisfaction and a quick fix.” (Paton). This expansion may reflect the current cultural propensity for instant solutions. Americans annually spend billions of dollars on the self-­‐help industry (The Medicated Child). Parents’ desire to alleviate their children’s symptoms of mental illness is understandable. The primary goal is to eliminate any psychological and emotional pain their child may be enduring, while promoting family stability is also an important motivator. However, this devotion becomes problematic when it becomes desperation. Self-­‐help websites, books, and speakers may lack reliable evidence and could take advantage of parents that need answers. For some parents, these “quick fixes” significantly impact their decision regarding the course of their child’s treatment. PBS Frontline’s 2008 documentary The Medicated Child showcases the Brain Matters Company. This business uses brain imaging technology to identify specific blood flow patterns that they believe are identifiers of behavior issues and mood instability. In one scene, a social worker explains the results of a brain scan and recommends pharmaceuticals to an 11 year-­‐ old client, Matthew. His father states: “I don’t understand the medical terms being used, but I think it’s pretty much on target” (The Medicated Child). Although the individuals evaluating Matthew are not trained medical professionals, his father readily accepts Brain Matters’ techniques and recommendations. Meanwhile, John March, M.D., Chief of Child Psychiatry at Duke University, explains: “We all want a simple, easy solution for these complicated life problems. My view…is if it’s too good to be true, it is, unfortunately, too good to be true” (The Medicated Child). Supporting this argument, Dr. Kiki Chang of the Bipolar Program at Stanford Gorson 3 University elaborates: “We’re at least five to ten years…off from that being a really reliable clinical tool. Right now, it’s strictly a research tool.” (The Medicated Child). Despite these expert opinions, Brain Matters has opened two more centers in major cities and is reaching thousands of Americans. Furthermore, the popular therapy television show “Dr. Phil” promoted this technology twice thus far. Companies like Brain Matters, self help books, and websites thrive off of parents’ urgent pursuit of answers. This tendency for labeling children as ill and needing medication exposes them to the risk of harmful side effects. In addition, using potentially unreliable technologies as a basis for the decision to medicate a child may cause unnecessary impact on the developing brain. (The Medicated Child) Another issue is the lack of a specific manual, such as the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), that contains diagnostic criteria of mental disorders particularly for children. Psychiatric diagnosis and treatment of children by pediatricians and even by psychiatrists is often entirely subjective and highly experimental (The Medicated Child). Thomas F. Oltmanns’s Abnormal Psychology states: “Children’s…disorders are not simply miniature versions of adult diagnoses” (Oltmanns 420). Furthermore, “The DSM needs to include more developmental considerations” (Oltmanns 441). The DSM contains only one section specifically about “disorders of childhood.” Unfortunately, it lacks information about serious mental illnesses such as bipolar disorder. Furthermore, distinguishing a childhood disorder that is historically present in adults is challenging because children have a different range of abilities to express their emotions. For instance, Gorson 4 sadness may be expressed as anger and frustration. Starting in the 1990s, experts and analysts proposed that instead of the persistent mood changes typically seen in adults, mania in children is demonstrated by extreme, unforeseeable and comparatively shorter episodes of irritability. (Oltmanns). Over the next decade, this suggestion caused an immense over-­‐diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children and the increased use of antipsychotics for treatment. Due to the current lack of understanding and available information regarding the diagnosis of children with traditionally adult disorders, the choice to treat them with medication can be short-­‐ sighted and potentially dangerous. Although some parents may argue that prescription drugs are absolutely necessary for their children, psychoactive medications can have a significant impact on the maturing brain. Thus far, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) only endorses the use of lithium, risperidone, and aripiprazole to treat young people with bipolar disorder (Bipolar Disorder in Children and Teens: A Parent’s Guide). The side effects of these medicines can be extensive. In one adolescent study, “Although all subjects had a family history of positive lithium response, only two subjects diagnosed with a bipolar illness showed a clearly positive response to lithium” (Scahill). Side effects of lithium include nausea, tremors, excessive thirst, and involuntary urination. This study also noted acne, abdominal pain, weight increases, diarrhea, and cognitive impairment. (Scahill) For children and adolescents, these side effects can be particularly devastating and embarrassing as they desire acceptance with peers. In addition, “because dehydration can increase lithium Gorson 5 levels and may induce toxicity, parents and children should be educated about the importance of adequate hydration.” (Scahill). The interaction of multiple drugs poses another risk as it can cause an elevation in lithium levels. (Scahill). Considering the many dangerous possibilities, medicating children seems to be a perilous endeavor. The Medicated Child emphasizes case studies that demonstrate the hazards and lifelong impacts of medicating children. The first child, Jacob, took eight different medications by age 10. He endured several diagnoses—including ADHD and anxiety issues—and had taken various stimulants, antipsychotics and antidepressants. After years of this treatment, his parents decided to hospitalize him and take him off all medications. Just one day later, Jacob was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and prescribed lithium. This point in Jacob’s life was the first instance in which his parents decided to explore alternative routes, such as therapy, in addition to the lithium. After mixing medications throughout his childhood, as a teenager Jacob developed a tic of rolling his neck. He also speaks slowly, demonstrating the cognitive impairment found in previous studies (Scahill). His tics did not cease when he stopped the medications. However, at age 16, his parents believed that his recent practice of yoga therapy had allowed him to “take control of who he is.” Jacob’s obvious cognitive difficulties and behavioral tics indicate the lasting consequences the medication had on his brain and the continuing harmful effect it has had on his development. (The Medicated Child). Another tragic case is that of 4 year-­‐old Rebecca Riley, who passed away due Gorson 6 to a drug overdose in 2006 (The Medicated Child). Police found her dead after her parents called 911 due to her lack of responsiveness in the morning (Darnton). Even at her young age, she was diagnosed and taking medication for bipolar disorder (The Medicated Child). “Rebecca was eventually prescribed three medications to stabilize her mood: Seroquel, an antipsychotic, Depakote, an anti-­‐seizure drug; and Clonidine, a blood pressure medication.” (CBS News). Her preschool teacher described her as a “floppy doll…so tired..she had to be helped off the bus. She had a tremor and had to go to the bathroom almost constantly.” (Darnton). The autopsy revealed that the amount of just one medication in her system was enough to kill her, in addition to the mix of drugs (Darnton). While there is uncertainty regarding the dose prescribed and the parents’ administration of the medication, there is no doubt that the medication was responsible for her death. This tragedy could have been avoided had a drug free or less pharmaceutically based treatment been used. Another child depicted in the film, 4 year-­‐old TJ, is also diagnosed with bipolar and takes three medicines as well. His mother describes his routine as: “focalin in the morning, focalin in the afternoon, clonidine to sleep at night, and respiradol to quiet tantrums.” (The Medicated Child). Respiradol is often used for young people with this diagnosis, yet TJ endures incessant hunger cravings, tics, and drooling from this medication (The Medicated Child). His mother describes him as “insatiably hungry.” She also relates, “He is so young, I don’t know the long term side effects. If he didn’t take it, I don’t know if we could function as a family.” (The Medicated Child). However, TJ’s poor eating habits that stem from the medication Gorson 7 could lead to diabetes and other health issues that eventually exacerbate his existing medical problems. These examples illustrate the distressing side effects that children may experience from pharmaceuticals. Alternatively, as The Medicated Child indicates, Jacob’s psychotherapy dramatically improved the quality of his life and his academic performance. (The Medicated Child). Therapy is also influential in Boy, Interrupted, a heartbreaking documentary of Evan Scott Perry, who committed suicide at age 15 after years of enduring bipolar disorder. At one point, Evan’s parents enrolled him in “milieu therapy” at a program called Wellspring (Boy, Interrupted). During this treatment, Evan learned that “actions have consequences and that boundaries are crucial for order and productivity” (Andrew). Therapists at Wellspring helped Evan battle his mental conflicts by assigning him purposeful activities. These projects allowed him to develop beneficial, therapeutic relationships. (Boy, Interrupted). His experience at Wellspring “added years to Evan’s life” (Andrew). Therapy has shown to be a successful part of childhood treatment. For instance, an analysis done in 1995 of over 150 studies using therapy for children showed “positive and highly significant” effects. (Weisz). As numerous studies have demonstrated, the choice to medicate a child has serious implications. By increasing the number of unnecessary diagnoses, the mounting influence of self-­‐help tools and the lack of specific diagnostic criteria for children may exacerbate these consequences. The cases of Jacob, Rebecca, and TJ demonstrate only a few harmful side effects, including cerebral functioning Gorson 8 impairment, torpor, weight gain, and even death. These children are a sampling of thousands more whose lives have also been significantly impacted due to psychoactive drugs. Alternatively, psychotherapy and cognitive-­‐behavioral therapy, which involves managing emotions and skill development, has been repeatedly supported in studies. Evan Scott Perry provides a particularly meaningful example of the importance of this treatment in a child’s medical care. Considering these ramifications, parents should fully comprehend the dangers of pharmaceutical treatment before giving a child medication. Gorson 9 Works Cited Andrew, Penelope. "Evan's Excruciating Choice: A Family Devastated and A Boy I nterrupted on HBO." The Huffington Post. TheHuffingtonPost.com, 08 June 2009. Web. 14 Mar. 2012. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/penelopeandrew/evans-excruciating-choice_b_249344.html>. "Bipolar Disorder in Children and Teens: A Parent's Guide." NIMH· What Treatments Are Available for Children and Teens with Bipolar Disorder? Web. 25 Mar. 2012. <http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/bipolar-disorder-in-childrenand-teens-a-parents-guide/what-treatments-are-available-for-children-and-teenswith-bipolar-disorder.shtml>. Boy, Interrupted. Dir. Dana Heinz Perry. 2009. DVD. Darnton, Kyra. "What Killed Rebecca Riley?" CBSNews. CBS Interactive, 11 Feb. 2009. Web. 14 Mar. 2012. <http://www.cbsnews.com/2100-18560_1623308525.html?pageNum=3>. The Medicated Child. Dir. Marcela Gaviria. PBS Frontline. 2008. DVD. Oltmanns, Thomas F, Robert. E. Emery. Abnormal Psychology. USA: Pearson, 2010. Print. Paton, Graeme. "Child Mental Health Fears Prompt Rise of 'Quick Fix' Drugs." The Telegraph. 16 Nov. 2009. Web. 14 Mar. 2012. <http://www.telegraph.co.uk/education/6583571/Child-mental-health-fearsprompt-rise-of-quick-fix-drugs.html>. Scahill, Lawrence, Leslie Farkas, Vanya Hamrin. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing. Vol 14. 2. 2001. Print. Weisz, John R., Bahr Weisz, Susan S. Han, Douglas A. Granger, and Todd Morton. "Effects of Psychotherapy With Children and AdolescentsRevisited: A MetaAnalysis of Treatment Outcome Studies." Psychological Bulletin 117.3 (1995). Web.