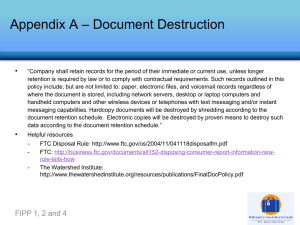

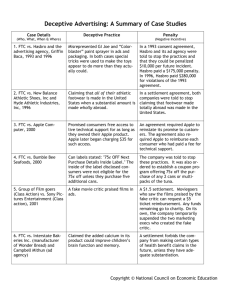

The Federal Trade Commission as an Independent Agency

advertisement