report - Spirit Inn of Mission Valley

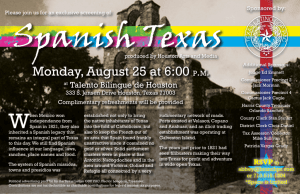

advertisement

El Camino Real in Victoria County A report to Victoria County Commissioners Court Monday, October 12, 2009 And to National Parks Service National Trails System Office Santa Fe, NM Prepared by Victoria County Heritage Department Gary Dunnam, Victoria County Heritage Director Dr. Robert W. Shook, Consultant 1 2 THE CAMINO REAL IN VICTORIA COUNTY Though Spaniards arrived in what is now Victoria County in 1689, 1 three decades passed before a permanent settlement was founded. These were decades during which the area was host to many entradas launched for the purposes of countering the threat of French encroachment on Garcitas Creek, gathering information relating to the frontier of New Spain, establishing a mission-presidio system, countering foreign intrusions on Spanish claims, and to guarantee against violations of commercial monopoly. 2 French competition for the region from Florida to the Rio Grande was the principal factor in Spain’s premature thrust north of the Rio Bravo in the 1680s; French intrusion continued for a century. Governor General Alonzo de Leon’s successful entradas of 1689 and 1690 to locate the French outpost, “Fort” St. Louis, 3 was the beginning of what would be a failed system of 1 It is important to note and know that Spaniards first approached what is now known as Texas from the west and east in the 1540s (Coronado and De Soto expeditions). The region in question in this examination, the Texas Coastal Bend, was observed from the waters of the Spanish Sea (Gulf of Mexico). With the exception of the adventure of Cabeza de Vaca, knowledge was limited to these observations. For this perspective see Robert S. Weddle, San Juan Bautista, Gateway to Spanish Texas, pp. 3-13. Victoria County’s niche in the larger picture of Spanish Colonial America was on what the paramount authority on the Spanish Borderlands, Herbert Eugene Bolton, referred to as the Eastern Corridor leading northward out of New Spain, a movement which received its impetus from events on Matagorda Bay. At that time and place two of the principal competitors for the New World set in motion a cycle of history which ended by 1890, the accepted date of the end of the frontier era of the United States. Understanding the background to Victoria County history is best begun in Charles Gibson, Spain in America, and Bolton’s, Texas in the Middle Eighteenth Century (hereafter cited as Bolton, Middle). See also John Francis Bannon, Bolton and the Spanish Borderlands, and Herbert Eugene Bolton, The Historian and the Man; the works of Felix Almaraz, Distinguished Professor of Borderland History; Robert S. Weddle’s numerous and superbly researched titles; and, a book of lesser reputation but useful, Caminos and Entradas, the Spanish Legacy of Victoria County and the Coastal Bend by Robert W. Shook (cited hereafter as Legacy). The New Handbook of Texas is the basic standard for factual material and is used in this study as a standard for verification in chronology and biography. Hobart Huson, Refugio: A Comprehensive History of Refugio County from Aboriginal Times to 1953. Hereafter cited as Refugio. Huson’s work is invaluable for understanding the neighboring county of Victoria. Robert S. Weddle’s caveat for local historians deserves attention. His warning is found in Shook, Legacy, p. 14. 2 A large number of the entrada routes found in Carlos Eduardo Castaneda, Our Catholic Heritage …, Vol. I, pp. 416-417, relate to Victoria County. Several of the earliest trails are unique to the county (hereafter cited as Castaneda, Heritage), Shook, Legacy, p. 106. 3 Robert S. Weddle’s preeminence in the field is based on a long list of titles found in the bibliography. Wilderness Manhunt and French Thorn are particularly useful here. Weddle warns against the use of the word “fort” in connection with La Salle’s outpost; its frequency of appearance in the preferred primary sources such as by Morfi’s History of Texas (Carlos E. Castaneda, editor), and Charles W. Hackett’s monumental Pichardo’s Treatise, both 3 missions and presidios in East Texas and the defense of Spanish claim to the lands of that region. After the early 1700s, Spanish Los Adaes and French Natchitoches became the points of imperial competition for Texas until the 1770s. Maintaining and supplying the Spanish presidios and missions there necessitated a network of trails over distances and around obstacles unknown to Spaniards. These “roads” through the vast wilderness that became Texas were indeed a “network,” migrating over time to meet the requirements of missionary and military strategy, permanent settlements, and European declarations of war and peace. Assignment of names for these Spanish roads was more complicated than often presented in popularized history. “Camino Real” (King’s Highway), for example, is a term derived from Spanish usage but often applied incorrectly. It appears to have met, in nineteenth century romantic literature, a demand for “euphony;” George R. Stewart, in his American Place Names contends this demand much affected literary tastes. As pointed out by a current authority on the Borderlands, Professor Felix Almaraz, the Spanish word “real” has several applications— monetary denomination, place or location, as well as reference to the Spanish Crown. One often encounters the argument that only certain settlements met population numbers required for use of the term Camino Real. Historians familiar with early trail accounts and maps made by those who used the trails will see the fallacy of this argument. In his opening remarks at the first meeting of the El Camino Real De Los Tejas National Historic Trail Association in San Antonio on October 1, 2007, Professor Felix Almaraz carefully pointed out that the term is applied without justification in Spanish documents, which has led to widespread misunderstandings on litmus tests for proper research, as is William Edward Dunn’s dissertation at Columbia University—available as Spanish and French Rivalry in the Gulf Region of the United States, 1678-1702, The Beginnings of Texas and Pensacola, University of Texas Bulletin, No. 1705: January, 1917, Studies in History No. 1, pp. 5-30. Herbert Eugene Bolton, “The Location of La Salle’s Colony on the Gulf of Mexico,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review (now the Journal of American History), September, 1915, Volume II, pp. 1-13. Hereafter cited “Location. “ 4 the part of those seeking to commemorate the roles of Spanish Colonial trails. 4 Professor Almaraz remarked pointedly at how infrequently the term “camino real” actually appears in Spanish documents from the period. More often than not, segments of the transportation network were recorded in Spanish records by names meant to convey destinations or origins of the routes. One such road was the Bexar-La Bahia-Nacogdoches Road or “Middle” Camino Real (depending on time, also seen as “Lower” Road). All such trails, by any name, emanated from a site and date of some importance—Garcitas Creek on April, 22, 1689. 5 It was there and then that Alonzo de Leon, after three prior land expeditions—and maritime expeditions by others—discovered the site of the French outpost of Rene Robert Cavalier, Sieur (Lord) de La Salle, whose purpose had been to use the outpost to gather information necessary to acquire Spanish territory which was rich in silver. 6 Thus began an extended effort by Spain to defend her claims and to civilize the North American Indians living in Texas. Several trails were blazed from the Rio Grande to implement these goals. Their routes are variously recorded in primary sources and secondary works. 4 At the initial public meeting of the Camino Real Association Professor Almaraz addressed the issue of useage of the term “Camino Real.” His argument of its unmerited application was based on his wide knowledge of Spanish records and maps. Readers should study Bolton’s, Map of Texas (1915); this extraordinarily accurate map and the well-known Austin or Galli Map (1826), and other early maps by Stephen F. Austin verify Almaraz’s commentary. 5 Rev. Francis Borgia Steck, “Forerunners of Captain De León’s Expedition to Texas, 1670-1675, Preliminary Studies of the Texas Catholic Historical Society, Vol. XXXVI, Number 1, July, 1932, pp. 5, 7. In Hackett’s, Pichardo’s Treatise, are found the numerous Spanish movements north of the Rio Grande prior to the De Leon entrada; these are often neglected in secondary works. The De Leon Itinerary, Llanos-Cardenas Map, and Barroto documents (Robert S. Weddle, editor, La Salle, the Mississippi, and the Gulf, Three Primary Documents) should be consulted here. They are found in Donald E. Chipman, Spanish Texas, 1519-1821 (cited hereafter as Chipman, Spanish), pp. 90, 94; in Herbert Eugene Bolton, Texas in the Middle Eighteenth Century, vii, and “The Location of LaSalle’s Colony on the Gulf of Mexico,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review (now the American Historical Review), September, 1915, Vol. II pp. 165-182. The copy used here is the rare reprint by The Union Nation Bank, Houston, Texas, 1929, pp. 6-13, which appeared in the Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. XXVII. The author establishes his claim here to the still unchallenged role of premier discoverer, through the Llanos-Cardendas Map, to the of the site of “Fort” St. Louis in Victoria County. 6 Shook, Legacy, pp. 69-80 5 Beginning in 1915, attention was focused on Spanish trails by the Daughters of The American Revolution. The admirable work of that organization laid the foundation for subsequent commemoration of Spanish Colonial History in Texas. Combined efforts during the Texas Centennial in 1936, were inspired by V. N. Zively’s work. 7 As mentioned above, Victoria County was host to a considerable number of the early Spanish trails of exploration and service to the East Texas Missions. In time, these trails suffered reversals of a magnitude that forced their suppression after 1774 for both economic and military reasons. Such mission-presidio establishments, and their withdrawals westward to San Antonio, resulted in a migration of Spanish trails southward to meet new needs, a pattern that continued to the end of the Spanish Colonial period. After withdrawal from East Texas, Spain attempted to rebuild, beginning in 1720, the abandoned East Texas mission-presidio complex. The task fell to Marqués de San Miguel Aguayo, José de Azlor y Virto de Vera. A serious French threat to Matagorda Bay had prompted orders to the Marqués that he also construct a presidio on the very site where Governor Alonzo de León had discovered and later burned La Salle’s outpost. 8 Returning to San Antonio from East Texas after establishing his reputation as leader of the most impressive entrada of the period, the Marqués joined the troops and padres dispatched to Garcitas Creek in 1721. The mission work there was already begun. 9 Aguayo officially conveyed the mission site to Father Patrón and drew plans for a presidio, Nuestra Señora Santa Maria de Loreto de la Bahia del Espíritu Santo, and a mission, Nuestra Señora del Espíritu 7 Handbook of Texas Online, s.v. Old San Antonio Road. The year 1915 was a propitious one, being the same year that Bolton began the publication of the innumerable Spanish documents he had discovered and translated in the Mexican and Spanish archives. 8 A summary of the Aguayo entrada is found in Shook, Legacy, pp. 186-215. 9 Ibid. 6 Santo de Zúñiga. 10 Thus were established two Spanish institutions whose short lives and relocations are legendary. By 1725 missionary efforts were well underway on a site known as Tonkawa Bank—on the Guadalupe River—in present-day Riverside Park, Victoria, Texas. Some time during the following year, both the mission and presidio were moved further inland. In General Pedro Rivera’s diary of an inspection tour of 1727 are seen his impressions of the new Presidio La Bahia. The site, now known as Mission Valley is located on the Guadalupe River about 8 miles upstream from Victoria. 11 Rivera’s report is the first fully documented account of the presidio on the Guadalupe River at this location. There the mission and presidio would remain until 1749, a critical date in the Spanish colonial period of Texas history. It is, in fact, true that this 23 years, which is apparently not fully understood, explains the on-going difficulty in acquiring official recognition of the middle branch as a major segment of the network of Caminos Reales. Rivera’s visita (tour) was the first of several inspections motivated by a need to reduce a fatal drain on the Spanish budget. Spanish records bearing on this span of 23 years are comparatively rare; Rivera’s description of his route of travel to Presidio La Bahia, his plan for irrigating the area, orders to reconnoiter the lower reaches of the Guadalupe River, 10 Ibid. Ibid., pp. 215-228. By 1727, when Pedro de Rivera y Villalon (NHT, Vol. 5, p. 598) conducted an inspection of the presidio on the Guadalupe River the Spanish presence on Tonkawa Bank in Riverside Park, Victoria was still under construction. Archeological excavations for this and the subsequent site about 7 miles up river confirm the historical records. Juan Antonio Bustillo y Ceballos (NHT, Vol. 1, p. 865) to viceroy, June 18, 1726. Typed translation by James Sutton, Archivist, Our Lady of the Lake College, San Antonio, to John L. Jarratt, January 21, 1968. Archives, Regional History Collection, Victoria College. Bustillo refers to himself as “Governor of this Presidio of Nuestra Senora de Loreto and of Bahia del Espíritu Santo.” This is one of several letters from Sutton in the John L. Jarratt Collection in which Sutton states his belief, with minor reservations, that Jarratt had discovered the second site of the mission. For later confirmation see Ann A. Fox, “Preliminary Report of Archaeological Testing at the Tonkawa Bluff, Victoria City Park, Victoria, Texas,” Center of Archaeological Research, The University of Texas at San Antonio, Archaeological Survey Report, No. 70, 1979, and V. Kay Hindes, “Primary Documentary Evidence for Three Locations of Mission Espíritu Santo de Zuniga: Clarifying the Historical Record,” 1995. The latter report does not include Fox as a reference, but both credit Jarratt with the essential, and first, investigation to verify Tonkawa Bluff as the second site of the mission. Conditions at Presidio La Bahia while located on the Guadalupe River are found in Castaneda, Catholic Heritage, pp. 84-88; Morfi, History, II, 295-299. NHT, Vol. 1, p. 865 11 7 and impressions of the state of preparedness of Spanish troops and competency of the commanding office are therefore quite useful. 12 Several Spanish officers served as captains of Presidio La Bahia at this location from 1726-1749, Juan Bustillo y Cevallos being the first. His successor, Joaquin Orobio y Basterra, earned a reputation as a superior commander when his presidio served as headquarters for three major expeditions and unsuccessful irrigation projects. 13 Orobio’s expeditions to the mouth of the Trinity River and Rio Grande significantly expanded the known portion of the province after 1747. It was his survey of the area between the Guadalupe and Rio Grande—under orders from the innovative colonizer, José Escandón, that led to the final relocation of Presidio La Bahia and Mission Espiritu Santo; more official designations for the fort and mission had, by this time, been abandoned for more convenient forms, notwithstanding their distance from Matagorda (Espiritu Santo) Bay. 14 During its residency on the Guadalupe River, Presidio La Bahia supplied troops to other posts including a military outpost, El Fuerte del Ciboló or Santa Cruz, on Ciboló Creek, about 60 miles to the southeast of Bexar (#1 on map), and to the San Xavier missions; La Bahia was 12 Establishing reasonably accurate routes for Spanish trails depends on reliable data concerning their destinations and the needs of those destinations. The trails served purposes dictated by the Franciscan officials, the viceroy of New Spain, the Spanish king, and ever-changing conditions on the frontier that came to be called Texas. Rivera’s commentary is supplemented by that of Governor Thomas Philipe Winthuysen (1741-1744) in this regard. Morfi, Part I, pp. 196, 216-217; Part II, 243-244; Hackett, Pichardo, Vol. IV, 192-193. 13 Mapping the Province of Texas; navigation of the Guadalupe Rive; irrigation of mission lands; procurement of salt from salines 150 miles south in the Nueces River region; orders and advice to the captain at Presidio La Bahia to accomplish these and other goals indicate the importance of Presidio La Bahia during 1726-1749. Winthuysen reported to the viceroy of conditions at the fort and, more importantly, its role as a way-station in Spanish strategy. Winthuysen to Viceroy, August 19, 1744, Bexar Archives, Vol. 5, p. 56-68. Orders to Joaquin de Orobio y Basterra (NHT, Vol. 4, p. 1168), captain of the presidio, 1736-1749, from Rivera, and Jose Escandon (NHT, Vol. 2, p. 889) were such that the role of Presidio La Bahia and its location from 1726-1749 leaves no doubt as to its situation and importance in Spanish strategy. Lists of officers and priests serving at Presidio La Bahia and Mission Espiritu Santo can be found in Kathryn Stoner O’Connor, Presidio La Bahia, 1721-1846, pp. 38-39. 14 La Bahia, over time, came to mean both Presidio La Bahia and Mission Espiritu Santo. On the San Antonio River after 1749 a civilian community grew up populated by presidiales (soldiers) and their descendants. In 1829 the anagram Goliad (Father Hidago, apostle of Mexican independence) was successfully championed by a former presidio captain, Raphael Manchola. 8 indeed a major factor in Spain’s Texas strategies. The site on Ciboló Creek contributes to the argument that the western portion (Presidio La Bahia on the Guadalupe to Bexar) of the Lower Camino Real, or Bexar-La Bahia-Nacogdoches Road, was a critical avenue. As part of Rivera’s economy campaign, the soldiers at this fort, and troops from Bexar and La Bahia, were factored into a strategy making them jointly responsible for responding to threats in East Texas where suppression of missions and presidios were expected. The following statement by Rivera in 1728 reveals the role of La Bahia in suppressing the East Texas establishment and thus the purpose of the Lower Camino Real: The distance between the presidio and Los Adaes is traversed by the soldiers in six or seven days, taking approximately the same time—a little less—to reach that of Bahia de Espiritu Santo. Consequently, upon learning at Los Adaes of a violation of the existing peace, the governor there could request twenty men from each of these two presidios and with these he would make up the one hundred in question…. 15 Fuerte (fort) Santa Cruz, mentioned above, was described in 1778 by Father Agustin Morfi as the “wretched fort of Santa Cruz.” In spite of the padre’s impression this site played a role in the history of the “western leg” of the Bexar-La Bahia-Nacogdoches Road (Middle Camino Real. From several sources it can be deduced that the outpost owed its origin to an effort to protect the San Antonio caballado (horse herd) during Apache raiding about 1731, but, as seen later, the location may have been known several years earlier. In any event the Ciboló outpost proved vulnerable, and the animals and troops assigned to guard them were withdrawn to San Antonio three years later. 15 Shook, Legacy, pp. 233-246. Refutation of the Rivera plan to reduce expenditures is found in Morfi, II, pp. 243279. The Rivera statement is supported by testimony by Governor Thomas Felipe Winthuysen. William C. Foster, Spanish Expeditions into Texas 1689-1768, p. 183. See also Russell M. Magnaghi, “Texas as Seen by Governor Winthuysen, 1741-1744,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. 88, 167-180. Using this and Winthuysen’s report of August 19, 1744 (Bexar Archives) Foster indicates “that the customary road from the presidio as San Antonio to the presidio at Los Adaes…and then east-northeast ‘about 40 to 50 leagues’ to the Brazos Dios.” 9 While San Antonio suffered from unrelenting Apache raiding that threatened the very existence of the Spanish settlement from 1731 to 1749, Santa Cruz functioned as a hinge or pivot-point from which hung two corridors seen on maps beginning in 1915 when Herbert E. Bolton chartered the contents of his masterful Texas in the Middle Eighteenth Century. The first was the trail from Bexar to Presidio La Bahia on the Guadalupe River via Paso La Laja (Rocky Ford) where present-day FM 537 crosses Ciboló Creek. This portion of the “western leg” was used from 1740 to 1749, according to reliable sources, but an earlier date, 1725, is indicated in a document of 1726. After the relocation of Presidio La Bahia to the San Antonio River in 1749 the trail dropped down to the new site from La Laja. The exact site of Santa Cruz still eludes historians and archeologists. The best estimate of its location is drawn from records indicating its distance (about 32 miles) from San Antonio and near La Laja ford on Ciboló Creek. By 1772, long after the presidio’s relocation in 1749, 20 Spanish soldiers and their lieutenant were posted at Santa Cruz. At this time the outpost’s location was given as approximately mid-way between Bexar and Presidio La Bahia and “off the road about 1 league [5.3 miles] to the north.” Robert Thonhoff, acknowledged authority on the site, recalls that the location of the fort, for many years, was thought to be on a hill near La Laja; contour line on a current map reveal two such hills but at a shorter distance from the ford. (see map attached). Barón Juan María Vicencio de Ripperdá, governor of Texas, recorded his role in the development of this Ciboló site: “I established it in 1771....” Five years later the Baron reported that the post “even yet …has not been built of stone.” 16 16 Juan María Vicento, Barón de Ripperdá was governor of the Province of Texas from 1770-1778. NHT, Vol. 5, p. 592. Bolton, Spanish Texas, pp. 28-29,108, 111. Jack Jackson in, “The 1780 Cabello Map: New Evidence That There Were Two Mission Rosarios, and a Possible Correction on the Site of El Fuerte del Cíbolo, “ Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. CVII, No.2, October, 2003, pp. 553-555, presents persuasive evidence on the issue of the initial site being unacceptable and the possibility of its relocation. 10 Ripperdá’s seat of authority was at San Antonio after 1772. Los Adaes, capital of the province, was relocated there at his suggestion. This decision necessitated finding new homes for the Adaesaños (settlers from Los Adaes who had been displaced by the withdrawal from East Texas); the site of Santa Cruz was one of several options considered for this purpose. Ripperda wrote of the site as “Fuerte del Zivolo” and “puebla of Santa Cruz del Ciboló.” Refugees from the San Saba massacre were likewise candidates for settlement on the Ciboló, and Ripperdá thought of the site as “one of his special achievements.” However, in 1778 Father Morfi found only “7 persons there.” The trail from Santa Cruz - located on Ciboló Creek near the La Laja crossing - (#2 N29°10’ W97°60’) 17 to the Guadalupe River migrated a short distance to the southwest after 1749 to serve Presidio La Bahia on the San Antonio River. However, the former location (known as Presidio Viejo or Rancho Viejo after 1749) was not abandoned. In fact, the fords there continued to be used on the route to Nacogdoches until circa 1788.18 Thirty-six years later, in 1824, the road would drop down seven miles to the new settlement of Guadalupe Victoria continuing, as it had from the Guadalupe, to Nacogdoches. As will be seen in due time, this first segment of this “western leg” is mentioned in the records was 1725, several years before the Apache attacks which are generally given as the genesis of the trail. Conclusive testimony is found in Spanish reports from several ranking officers as to the purpose of this road. In addition to those previously mentioned, the words of Governor Prudencio de Orobio y Basterra (not to be confused with Joaquin de Orobio y Basterra, 17 All map references are keyed as in this example, to the attached map. For the locations of Paso La Laja, Fuerte Santa Cruz and the route and name of the road from La Bahia (Goliad of later times) to Bucareli and Nacogdoches see Jack Jackson, Los Mesteños, pp.59, 92, 324. Page 59 is especially recommended as it contains Jackson’s efforts to determine the boundaries of Mission Espiritu Santo. He concludes the mission pastures were “bounded on the north by the road to some military post on the Guadalupe (most likely the overland road between Béxar and Espíritu Santo…” 18 11 NHT, Vol. 4, 1168) confirm the location of Presidio La Bahia, and no other, during the years that the Bexar-LaBahia-Nacogdoches or Camino Real was used. Writing at Los Adaes on July 8, 1740, the governor stated, in part: “…between said coast [Gulf of Mexico] and the Camino Real which we travel from here to La Bahia….” Four years later Don Thomas Felipe de Winthuysen, writing in San Antonio, reported that At a distance of sixty leagues from this presidio, to the south, the Presidio of Bahia del Espiritu Santo is located on the banks of the Guadalupe River. This presidio has always been in a state of deterioration due both to the scarcity of stone and lumber so that the roofs, especially, because they are of zacate (grass), have always been subject to great conflagrations, and to the fact that there has been much illness there….although there are many Indians in the mission…only a few are Catholic…because of the uncertainty of the crops, whenever these fail, the…priests are compelled to send the Indians away for that year until the next… This is the point of departure for the presidio of los Adays, the capital of said province…. There has been misunderstanding and confusion concerning the fact that Presidio La Bahia was located for 23 years (1726-1749) on the Guadalupe River some 7 miles above present day Victoria, Texas. The confusion has resulted in errors, minor in terms of miles but highly significant to an understanding of the trail in question, on maps and text published by the National Park Service, Texas Department of Transportation, and in the local press. 19 Contrasting with these sources are others, both cartographic and textual. 20 At this point it is useful to observe that several obstacles complicate the tracing of Spanish trails. Present county lines obscure the realities of the colonial period, and teleology (a 19 Bolton, Spanish Texas, pp. 63-64. The Winthuysen quotation is found in the Bexar Archives, Vol. 15, pp. 56-68; James Sutton’s translations and comments are available in the Jarratt Collection, Victoria College-University of Houston, Victoria Library. NHT, Vol. 6, p. 1027. The reasons for the errors are clear in National Park Service publications in 1991 and an internal directive to correct the errors. Articles appearing in the Victoria Advocate on this subject are incorrect and inaccurate. Newspaper coverage of this type date to 1914 when coverage of Bolton’s trip to Victoria evoked the visitor complained of a sensationalized announcement of his discoveries. Accurate routes in Texas Parks and Wildlife publications in 1987 and 2004 (PWD BR4502-063 8/04) were ignored during a 1991 study of the route. That situation continued to the present time. 20 The route of the road is seen on several maps, e.g. the “Galli” map of Austin’s design and on one by Jack Jackson, Los Mesteños, pp. 59 & 324, on which the author plots his investigation of the pasture lands of Mission Espiritu Santo. 12 kind of Monday-morning quarterbacking based on what is desired rather that proven) distorts the routes and their purposes. Herein lies the reason for much of the debate over trail routes, Spanish camp sites, and even geographic features found in secondary works that have received popular acclaim. Avoiding these obstacles is made somewhat easier when population density, details of travel (distances, estimated speed, and trail hazards), and attention to map scale are factored into calculations and interpretations. 21 It is also worth noting that reliable, and still recognizable, geographic references points must first be established in this process of trail searching. Failure to do so is to fall prey to superficiality. In a roughly descending scale of reliability, river and creek bends, springs, fords, and translations of French, Spanish, and even Indian words serve as references once the Spanish entrada records, Anglo travel memoirs, and field surveys are consulted. One can expect to see the Spanish trails migrate, over the years, on successive maps. One last caveat remains. Rejecting data appearing on maps drafted a century or more after the decline of Spanish trails is unwise because, until the advent of steam and gasoline powered vehicles, the horse, mule, and ox dominated transportation routes. 22 Streams, large and small, fords and other geographic features change, at least in rural areas, little over relatively short periods of time. The first documented reference to a road in the immediate vicinity of Presidio La Bahia on the Guadalupe River is imbedded in a report—dated June 18, 1726—by Juan Antonio Bustillo y Cevallos, “Governor of this Presidio of Nuestra Senora de Loreto and of Bahia del 21 Until the general hypotheses of history are put to the test at the local level they remain hypotheses. However, as Robert S. Weddle has correctly defined it, “One-shot local histories are probably responsible for spreading more myths that any other kind, with university professors writing solely for professional advancement running a close second.” It is also important to point out that archeologists and historians are not often acquainted with the work published in their separate disciplines. A survey, by the author, of publications by the former scholars indicates an absence of documentation based on Morfi, Pichardo, and early maps. See article by Anne A. Fox in bibliography. 22 For a discussion of applied map skills see A. Joachim McGraw and James E. Corbin, book review of “Spanish Expeditions into Texas 1689-1768” and rebuttal by William C. Foster, Bulletin of the Texas Archeological Society, 70/1999. 13 Espiritu Santo, “ to the viceroy of New Spain. Bustillo, referring to a more desirable site for the existing missionary activity on Tonkawa Bank in present-day Victoria, testifies that it would be “necessary to establish another Mission, by a copious creek which I have surveyed on the new road I opened to the Rio Grande. This road, if verified, would have preceded the Bexar-La Bahia-Nacogdoches Road or Lower Camino Real by fourteen years and was perhaps a trail on which the western leg of the Lower Camino Real was founded.24 Essential to an understanding of the Bexar-La Bahia-Nacogdoches Road, a segment of the network best known as Los Caminos Reales, is the Apache threat to Spanish presence in the Province of Texas. Apache raids on Bexar during the years from 1731 to 1749 resulted in such loss of horses that the cavalry units there were reduced to ineffective infantry. Spanish officials were thus forced to open a new route to East Texas. It was this southern detour that appears in their records as the Bexar-La Bahia-Nacogdoches Road and Camino Real, recorded as the Middle Camino Real or Lower Camino Real. The following argument provides documented evidence of river-fords, and other sites, which connected Bexar and Presidio La Bahia over which the “western section” of the Bexar-La Bahia-Nacogdoches Road ran from about 1731 to 1749. The latter date marks two additional events which define this “western section” - a peace treaty with the Apache, and the relocation of both Presidio La Bahia and Mission Espiritu Santo from the Guadalupe to San Antonio River. The first fact in this body of evidence is circumstantial but important. Alférez (junior lieutenant) Bernabé Carbajal received a grant of land for what became known as Rancho de Cleto or, Rancho de Los Corralitos, in the upper region of lands allocated to Mission Espiritu Santo in November, 1755. He testified some years later that he had settled this tract of land in 14 1741. 23 This would have been while he was stationed at Presidio La Bahia on the Guadalupe. It is improbable that he lived on this ranch, but Carbajal was one of the first soldados to compete for ranch lands in what would become the vast pasture of Mission Espiritu Santo after 1749 when the mission was relocated on the San Antonio River this grant to a Spanish soldier is the first of a long list of cattlemen who inherited mission pastures after their suppression.. The key to tracing this “western” segment of road in question is the site of Santa Cruz, a Spanish military outpost on Ciboló Creek. The role of Santa Cruz is understood only after the realization that the site was what might be called a hinge from which two roads dropped southward. The earlier road (1725-1749) led to the Presidio La Bahia on the Guadalupe River (#3 - N28o52’ W97o5’) 7 miles north of Victoria, Texas. The later road dropped southward to the same Presidio after its relocation to the San Antonio River, in 1749, a site known since 1829 as Goliad. The vacated site on the Guadalupe would continue to serve as a ford where Mission Creek empties into the Guadalupe; Spanish era maps label this vacated site as Presidio or Rancho Viejo. It remained a way station on the “Middle” Camino Real until it moved southward to cross the Guadalupe downstream at the new empresario colony of Guadalupe Victoria founded in 1824. The “wretched” fort of Santa Cruz is found in numerous 18th century sources. 24 Its role as a “hinge” is, of course, derived from a comparison of the roads that connected the ford La 23 Jack Jackson in his peerless study of early ranching, Los Mesteños, 58-61, discusses the relationship of mission pasture lands to the route of the Bexar-La Bahia-Nacogdoches Road. A graphic presentation of his exhaustive study of the northern limits of the Mission Espiritu Santo lands appears on p. 324. It clears shows La Laja, or Rocky Ford, which marks the nearby site of Santa Cruz outpost. Bolton’s map of 1915, still considered the most accurate depiction of Spanish Texas, is even more value in establishing the location of Santa Cruz. 24 Documents referring to Santa Cruz and the Apache raiding are found in Morfi, II, pp. 348fn 17, 420. The Puellas Map of 1780 and the 1807 version, pinpoint Presidio Viejo. The Jackson article on the subject in the Southwestern Historical Quarterly, CVII, No. 2, October, 2003 is useful. Topographical Map of the Country Between San Antonio & Colorado River in the State of Texas, Engineer Department, Topographic Bureau, District of Texas, New Mexico & Arizona, A.D. 1864, National Archives, Record Group 77, Z49-1, provides an extraordinarily detailed sketch of 15 Laja, which served the outpost and the trails to both sites of Presidio La Bahia—on the Guadalupe River (1726-1749) and on the San Antonio River (after 1749). The “eastern” leg of the road—from Presidio La Bahia to Nacogdoches—presents less of a problem in tracing its route than does its “western” counterpart. Guadalupe River, approximately 7 miles 25 From the site on the (line of-sight and 2.37 miles downstream from the mission) upstream from present day Victoria, Texas, the Camino Real led to a crossing on Garcitas Creek about 1 ½ east of U. S. Highway 77 (#4 - N28o57’ W96o58’). The trail then crossed the Lavaca River (#5 - N29o8’ W96o50’). This crossing, on a bearing of 33 degrees from the presidio, was 22.8 miles (line-of-sight) from the presidio. This historic ford lies 1.27 miles (bearing 220.9 degrees) from the termination of Lavaca County Road No. 1 at Highway 111. It is a crossing seen on numerous early maps and more recently on property maps. 26 From the ford on the Lavaca River (two previous fords are likewise obvious—one on Arenosa, the other on Chicolette Creeks) the Camino Real ran to a crossing on the Navidad River, a line-of-sight distance of about 9 miles (the road apparently laid the path for the county road mentioned above). This Navidad River ford (#6 N29°12’ W96°44’) was located just below where Hardy’s Sandy or Sandies Creek empties into the Navidad River. This area is the area in question. The value of this document is in no way diminished by its date of production; on the contrary, as long as the horse and wagon were the means of transportation, it proves the long-lived character of useful fords. 25 These long-used Spanish fords on the Guadalupe River were essential ingredients in the boundary claims of Empresarios Green DeWitt and Martin de Leon in the testimonies of their surveyors and themselves after 1824 and the littoral coastal reservations that complicated their settlement. Later county lines were frequently dependent on the ford. 26 Topographical Map of the Country Between San Antonio & Colorado River in the State of Texas, Engineer Department, Topographic Bureau, District of Texas, New Mexico & Arizona. A.D. 1864, National Archives, Record Group 77, Z49-1. This map shows natural features, roads, homesteads, and notes on supplies. It has long been known but little used because of its being available, until recently, only in the form of damaged, printed negatives which require computer enhancement. See property maps of Lavaca and Victoria and Land Deed records of both counties as well as the several descriptions of the De León Empresario Colony boundaries. Also the descriptions, by Martín de León and surveyor James Kerr in which are seen key fords dating to the Spanish period. Eugene C. Barker Stephen F. Austin, Austin Papers, s.v. 16 known as Gandy Bend. These fords on the Lavaca and Navidad Rivers are best seen on an extraordinarily detailed map drawn in 1864. A unique opportunity to stand on this road is still available at approximately #7 - N29o17’ W96o39’. It is at this approximate grid reading that Tom Byrd, a former cartographer whose family owns this property, has conducted a careful study of this section of land between the Navidad and Colorado Rivers and allowed the author to visit the site. 27 The next documented crossing is well known, the Colorado River just south of present-day Columbus (#8 - N29o44’ W96o31’) From the Colorado River the road ran, for approximately 32 miles (bearing approximately 42o), to Raccoon Bend (#9 - N30°1’ W96°51’) on the Brazos River where Waller and Austin Counties share a boundary. This ford site was researched by James Woodrick of Austin, Texas, whose admirable efforts to plot the Coushatta Trace are pending publication. Richard Senasac, Chairman of the Waller County Historical Commission was most helpful in identifying the settlement of Raccoon and the names of its historic fords. The next documented crossing of the Lower Camino Real is well-known. It was Paso Tomas on the Trinity River (#10 - N31°5’ W95°42’), where the settlement of Nuestra Senora del Pilar de Bucareli, was founded for the family and followers of Gil Ibarbo. The ford in later years was known as Robbins Ferry. It was here that the road from Bexar and La Bahia to Nacogdoches and the older road from Bexar to Nacogdoches met, crossed the Trinity River, and continued to Nacogdoches. 28 #11 on map 27 Topgraphical Map of the Country…. above. The Colorado River crossings at Columbus were, by 1864, a web of fords along the loop in the river above Columbus and reaching downstream to the Alley property. The John D. Ragsdale league of 1826, as seen in Virginia Taylor, The Spanish Archives of the General Land Office, p. 230 and early surveys of the area, was clearly on the route of the trail in question though the fact that the Atascosito and Middle Camino Real merged before crossing the Colorado River accounts for the former designation appearing in local sources. 28 Bolton, Texas, pp. 405-411 is the definitive treatment of this pass and its role. NHT, Vol. 4, 1168-1169. 17 From a number of primary sources several are chosen to amplify the sites along the route of the Bexar-La Bahia-Nacogdoches or Camino Real branch often found in the records as the “middle road.” The most convincing evidence of the route of the “eastern leg” of the Bexar-La Bahia Road calls on nothing more than the understanding that Los Adaes, capitol of the Province of Texas and Presidio La Bahia were distinct and the latter was located on the Guadalupe River 7 miles north of present-day Victoria, Texas, in 1740; this fact is disputed in no known source, primary or secondary. Governor Prudencio de Orobio Bazaterra (not to be confused with Joaquin Orobio Bazaterra), writing on July 5, 1740, to the president of the missions at San Antonio, comments on the lack of information regarding the coastal region of the Province of Texas, and identifies the Bexar-La Bahia-Nacogdoches or Camino Real: “…between said coast and THE CAMINO REAL WHICH WE TRAVEL FROM HERE [LOS ADAES] TO LA BAHIA.” Only one site satisfies the governor’s use of La Bahia—its location some 7 miles above present Victoria. The presidio was located at this site from 1726-1749, and it must be assumed that the Governor of the Province of Texas knew its location and the route thereto better than authors of current secondary works. It is likewise reasonable to assume that Captain Joaquin Orobio, commander at Presidio La Bahia in 1746 when he conducted an expedition to the lower Trinity River, was acquainted with Spanish trails of the period. His entrada to the Trinity completed, he “struck northwestward to the camino real leading from Nacogdoches, and returned to La Bahia [at the location cited above] where he arrived on April 6.” 29 As seen earlier, the “western” segment of that branch of the Camino Real network (Bexar-La Bahia-Nacogdoches Road) is more difficult to trace precisely. However, with the 29 Bolton, Texas, pp. 331-332. These are among the many pages devoted by Bolton to his impeccable research concerning the Orcoquisac Indians and their habitat on the Lower Trinity River 18 available sources at hand, the route and use of this section of the road from about 1725 to 1749 are quite clear. Solving the puzzle of the routes of old Spanish roads requires acceptance of certain premises or rules of procedure. Rule number one is to subordinate secondary works to contemporary or eyewitness accounts. These constitute “admissible evidence.” Rule number two requires that we not forget that weather, foreign incursions, European states of war and peace, availability of Spanish reports previous to the ones in question, and even entrada commanders’ caprice affected trail routes. Claims of exactness in tracing the old roads have often proven disappointing. Peerreview publications invariably produce disappointment for the novice and professional historian alike when they commit to data which does not comport with prevailing conditions in eighteenth century Texas, which are described in the Spanish, French, and Indian languages. Though secondary works are to be avoided when primary sources can be found, one title is of such reputation that it is included in this study. Jack Jackson, whose research is recognized as impeccable, presents in his award-winning, Los Mestenos, a careful study of the linderos (boundaries) of the pasture lands assigned to Mission Espiritu Santo on the San Antonio River. Jackson’s research shows that the northern limit of that extensive pasture was a “the road to some military post on the Guadalupe most likely the overland road between Bexar and Espiritu Santo Presidio when it stood on the Guadalupe.” Jackson further concluded that his primary sources led clearly to a ford on Ciboló Creek, La Laja, now Rocky Creek ford, about 4.6 miles southwest of Stockdale. This ford is found where FM 537 crosses Ciboló Creek. It was a landmark on the northern lindo. Eastward, Jackson reports, the boundary crossed the headwaters 19 of Cleto (present-day Ecleto) Creek. 30 On a current USGS map it can be seen that both county boundaries and highway routes strongly suggest this pasture boundary and ford were of such remembered importance that they were fundamental to modern map features. Such a conclusion is consistent with examples found elsewhere where long-used fords and other natural features were originally the only landmarks available to surveyors. On June 18, 1726 Juan Bustillo y Cevallos, commanding officer of Presidio La Bahia on Garcitas Creek, stood on a precipitous bluff on the Guadalupe River—a site is now known as Tonkawa Bank in Victoria’s Riverside Park. The Captain’s observations at this location were reported to the viceroy. In addition to his comments relating to the nascent missionary activity on the bluff, Bustillo mentioned the need for a more suitable site upstream, because of the sizable number of Indians gathering at Tonkawa Bank; within a year’s time this new site, the third location of Mission Espiritu Santo, was founded, and its ruins can still be seen. As seen previously, Bustillo described a “copious creek which I have surveyed on the new road I opened to the Rio Grande, a distance of about three leagues [7.8 miles] from the site designated from the Presidio and which has a large saca of water that will irrigate a large area of land.…” The creek would have been a reference to what is now known as Mission Creek, used unsuccessfully to irrigate land near Mission Espiritu Santo. His “new road” would have connected Presidio La Bahia to Bexar. Bustillo’s “new road…to the Rio Grande” at this point becomes most significant. A combination of sources will make this clear. Carlos E. Castaneda (Our Catholic Heritage in Texas, Vol. III, pp. 86-90) summarized life at Mission Espiritu Santo, located two miles upstream from Presidio La Bahia, as critical for a period of ten years, because of serious shortages in supplies of every sort. This was due in large part to the failure of the irrigation 30 Jackson, Los Mestenos, pp. 59, 324. 20 system to provide sufficient water to produce the crops necessary to sustain Spaniards and the Indians. This state of affairs required importation from Bexar in order to maintain the missionaries, their wards, and presidiales (soldiers). The latter, stationed at Presidio La Bahia were often assigned to serve as guards at the San Antonio missions and to escort supply trains between Bexar and the presidio and mission on the Guadalupe River. At their previous sites on Garcitas Creek, both mission and presidio were supplied by boats from Vera Cruz. However, an unforeseen difficulty arose at the new location: the Guadalupe River proved to be un-navigable from the bay to the new location, necessitating all supplies be brought overland from Bexar. In fact, the record is replete with the goods transported—clothing, arms and ammunition, corn, candles, tobacco, chocolate, military orders, etc.—and even complaints and arguments between the regular clergy and presidial commanders concerning the number of soldiers and priests assigned to various posts. Castaneda points out the differences in distance from Presidio La Bahia and San Juan Bautista (researched by Robert S. Weddle in San Juan Bautista, Gateway to Spanish Texas), the principal source of supplies for the Province of Texas until about 1755 when Laredo inherited that role. San Antonio being the nearest source of supplies for Presidio La Bahia and Mission Espiritu Santo, it must be concluded that a road served all these purposes after 1726. It would thus appear that Bustillo’s “new road…to the Rio Grande” would have connected at San Antonio with San Juan Bautista on the Rio Grande. These conclusions being accurate, it seems prudent to propose that this “new road” was a precursor to what has been often referred to as an “alternate route or detour” from Bexar to Nacogdoches. Most often found in the historical literature for the “detour” southward, then to the northeast, was the need for a safer route from Bexar to Nacogdoches. The older, traditional road (Upper Road or Camino Real) had 21 become increasingly dangerous after 1731 when Apache attacks threatened the very existence of Spanish presence in Texas. Since Bustillo’s report to the viceroy, seen above, was dated 1726, it stands to reason that a well-known route from Bexar to La Bahia was in place several years prior to the deadly Apache attacks. This “western leg” of the Bexar-La Bahia-Nacogdoches Road—found by several names in Spanish and English documents—thus takes on a longer life and changing purposes as did all Spanish trails through the Province of Texas. 31 A 1987 a Texas Parks and Wildlife publication, Spanish Missions and Presidios in Texas (PWD BR 4509 063D 5 88), reprinted in 2004, clearly shows the entire road referred to in this study as the Bexar-La Bahia-Nacogdoches Road, known also as the Lower or Middle Camino Real and other names. 32 This detour from San Antonio to La Bahia was used until 1749, at which time Presidio La Bahia and Mission Espiritu Santo, now within the scope of Jose Escandon’s innovative plan for the civilian settlement of Texas, were moved—in October of that year—to the San Antonio River. Presidio La Bahia on the Guadalupe River thereafter would appear on early maps as Presidio Viejo or Rancho Viejo (old fort or old ranch). The “detour” in question would, as seen earlier, migrate southward with essentially the same purpose. 31 Correspondence between Bustillo and Governor Almazan, who verified the captain’s observations, is found in Sutton-Jarratt Correspondence, Jarratt Collection, Regional History Collection, Victoria College-University of Houston, Victoria Library. Boundaries of the Departments of the Province of Texas, and studies of the boundaries of present-day Texas counties, offer proof that knowledge of the route of Spanish trails and the fords over which they passed, many years after abandoned, became land marks reflected in surveyors’ field notes and county boundaries after 1846. Robert H. Thonhoff confirms this fact as a result of his research along Cibolo Creek, Conversation Thonhoff to Shook, October 3, 2009. 32 This map has not appeared in trail literature. According to the spokesperson of the Department, the cartographer or artist who rendered the map cannot now be identified. 32 See the Puellas and “Galli” maps of, respectively, 1780 and 1807 and the manuscript by Charles W. Ramsdell, Jr., of 1936, Center for American History, University of Texas, Austin. Incidentally, this source must not be discounted because of lack of documentation. As J. Frank Dobie—who was in a position to know—testified, it was based on primary sources. Ramsdell, Jr. learned his craft from his father, a long-time faculty member at the University of Texas. 22 The road to Nacogdoches continued to pass through the abandoned sites on the Guadalupe River to cross the upper Garcitas and Arenosa Creeks to the same fords on the Lavaca and Navidad Rivers identified earlier. Presidio Viejo or Rancho Viejo did not disappear from the Spanish record, however. Jacals there, apparently to shelter vaqueros (cattle herders) and, for a time, the site was a camp for Indians who preyed on the new ranch belonging to Mission Espiritu Santo, which became Goliad 80 years after its relocation from the Guadalupe River. 33 The migration of the Bexar-La Bahia-Nacogdoches Road to the San Antonio River in 1749 left what we now call Victoria County without another permanent settlement until 1824 when Empresario Martín de León established Villa Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de Jesús Victoria 7 miles downstream from the old presidio. After 1824 the Bexar-La Bahia- Nacogdoches Road ran to that new villa over a lower Guadalupe River ford before crossing the creeks and rivers mentioned earlier to the same destination of Nacogdoches. 34 Rivers, creeks and vados (fords) were the references for travel until the 20th century. They remain, once indentified, the chief clues to trail routes as those routes take their place on the agenda of tourist promotion; contemporary maps, memoirs, diaries, itineraries, land deeds, probate records, surveyors’ field notes, and genealogical charts, are the admissible evidence for proof of routes. County boundaries are comparatively recent inventions. They had nothing to do with Spanish Colonial history in Texas. They confuse the novice researcher, but since 1846 they are the major guides—the county clerk’s office for example—to several of those sources of information listed above. Local public and private libraries, university general and special collections, and state agencies—especially the General Land Office—hold many more. The primary or contemporary source is always superior to secondary works—books, articles, 34 Weddle, in San Juan Bautista, pp. 288-289, gives an example of the strategic value of Presidio La Bahia after the 1749. See also Shook, Legacy, pp. 283-287. 23 newspaper columns, and folklore—just as a case in litigation where the “eye-witness” takes precedence over “hearsay.” “Evidentiary protocols” have their roots in the long-ago Medieval universities when America was only a dream; they are common tools of the professional historian, legal scholar, serious genealogist and journal editor. Adopting the protocols will save the trail researcher disappointment. Shortcuts may satisfy the “pop” culture, but may cost time and money. BIBLIOGRAPHY PRIMARY SOURCES Barker, Eugene C., editor, The Austin Papers, 3 vols., The American Historical Association, U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C., 1928 . _________________, Charles Shirley Potts and Charles W. Ramsdell, A School History of Texas, Row, Peterson & Company, Chicago, 1912. Barnard, Dr. I. H., Barnard’s Journal, Goliad Advance Guard, 1965. Bolton, Herbert Eugene, editor, Spanish Exploration in the Southwest, 1542-1706, Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1908. Reprint, Barnes & Noble, Inc. 1946. Cotner, Thomas E. and Carlos E. Castañeda, editors, Essays in Mexican History, Institute of Latin American Studies [festscrift for Hackett], University of Texas, Austin, 1958. Reprint 1972. Greaser, Galen, New Guide to Spanish and Mexican Land Grants in South Texas, Texas General Land Office, Austin 2009. Hackett, Charles W., editor, Historical Documents Relating to New Mexico, Nueva Vizcaya, and Approaches Thereto, to 1773. 2 vols. Washington, 1923-1926. ____________________, translator and editor, Pichardo’s Treatise on the Limits of Louisiana and Texas…. 4 vols., University of Texas Press, Austin, 1934. Reprint, Books for Libraries Press, Freeport, New York, 1971. Itinerary Don Manuel Becerra, Guide on Stephen F. Austin expedition of Sept., 1821, Spanish Collection, Box 126, Folder 6, p. 72, General Land Office of Texas, Austin. 24 Land Deed Records, Victoria County, Texas, Office of the County Clerk, Victoria County, Texas. Morfí, Juan Agustín, History of Texas, 1673-1779, edited by Carlos E. Castañeda, The Quivera Society, Albuquerque, 1935. New Spain and the Anglo-American West, Historical Contributions Presented to Herbert E. Bolton [festschrift], 2 Vols., Kraus Reprint Co., New York, 1969. Pennybacker, Anna J. Hardwicke, A New History of Texas for Schools, Percy V. Pennybacker, Palestine, Texas, 1895. Probate Records, Victoria County, Texas, Office of the County Clerk. Property Abstracts and Aerial Photography, Victoria County Appraisal Office, Victoria, Texas. Report of Inspection by General Don Pedro de Barrio Junco y Espriella of Presidio La Bahia, November 11-30, 1749, Bexar Archives, translation, 22XXll, 2Q3227, 57 pages. Copy in possession of author. State Abstracts of Victoria County to August 31, 1941, General Land Office of Texas. Surveys of Guadalupe Victoria, 1833 (Carbajal), 1834 (Kerr) Archives, Spanish Collection, General Land Office of Texas. Copies in possession of author Surveys of Victoria County, Edward Linn, 1851-1857, 4 Vols., Office of County Clerk, Victoria. Copies in possession of author. Sutton-Jarratt Corresponence, translations of reports to viceroy from Captain Juan Antonio Bustillo y Zevallos and Governor Fernando Perez de Almazan, June 18, 1726July 4, 1726; Auditor to viceroy, August 19, 1726. Provincias Internas, Volume 236, University of Texas Archives. Report of Governor Don Thomas Felipe Winthuysen August 19, 1744, Bexar Archives, Vol. 15, pp. 56-68. Copies in Jarratt Collection, Regional History Collection, Victoria College-University of Houston, Victoria Library. Texas by Terán, Jack Jackson, editor, University of Texas Press, Austin, 2000. Town Lot Titles, Guadalupe Victoria, 1833-1835, manuscripts, Spanish Collection General Land Office of Texas, Archives. Copies in possession of author. The State of Texas v. City of Victoria, No. 15863, 309 South Western Reporter, 2nd Series. Documents of Texas History, Ernest Wallace and David Vigness, compilers and editors, Odie B. Faulk, translator. The Steck Co., Austin, 1963. 25 Weddle, Robert S, editor, La Salle, the Mississippi, and the Gulf, Three Primary Documents, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 1987. White, Gifford, Citizens of Texas, 1840, 2 Vols., Austin, 1983. Copies in possession of author “Zacatecan Missionaries, 1716-1834…,” translated by Fr. Benedict Leutenegger, and a Biographical Dictionary by Fr. Marion Habig, Texas Historical Commission, State Acheological Reports, no.23. Copy in possession of author. MANUSCRIPTS “Archaeology (The) of Goliad and Victoria Counties, Central Coastal Plain of Texas, selected reports and exerpts, A reader for students in the 1995 summer field school of the Department of Anthropology,” The University of Texas at Austin, June 1995. Copy in possession of author. “Autobiography of James Norman Smith,” manuscript, Center for American History, University of Texas. Crimm, Ana Caroline Castillo, “Success in Adversity,” doctoral disseration, University of Texas, 1994. Drushel, Lon, “A Possible Site of LaSalle’s Fort St. Louis,” Archeology Lab Library. Copy in possession of author. Dunn, William Edward, Spanish and French Rivalry in the Gulf Region of the United States, 1678-1702, The Beginnings of Texas and Pensacola, [doctoral dissertation] University of Texas Bulletin, No. 1705: January 20, 1917, Studies in History No. 1. Reprint Kessinger Publishing Rare Reprints, 1998.. Mclean, Malcom D., Voices from the Goliad Frontier, Municipal Council Minutes: 1821-1835, William P. Clements Center for Southwestern Studies, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas, 2008. Faulk, Odie B., “The Last Years of Spanish Texas, 1787-1821,” doctoral dissertation, Texas Tech University, 1962. Ramsdell, Charles W. Jr., “Spanish Goliad,” typed manuscript, Center for History, University of Texas. Copy in possession of author. American 26 Shook, Robert W., “Federal Occupation and Administration of Texas, 1865-1870,” doctoral dissertation, University of North Texas, 1970. Santiago, George A., “Don Carlos de la Garza,” typed manuscript. Copy in possession of author. Tennis, Cynthia L., compiler and editor, Archaeological investigations at the last Spanish Colonial mission established on the Texas frontier: Nuestra Senora del Refugio (41RF1), Refugio County, Texas, Texas Department of Transportation, 2002. “Testimony taken by Fernando Perez de Almazan, Governor and Captain General of the Province of Texas/New Phillipines, at the Bahía de el Espiritu Santo, regarding the deaths [of] two soldiers killed by the Indians who were guarding the horse herd of that presidio on January,13, of this year, 1724,” Num. 9 of the papers of the superior government, 1282. Copy in possession of author. Victoria Advocate (The), Victoria, Texas, 1850-present, microfilm, Victoria College/University of Houston Library. Woodrick, Jim, “The Coastal Bend Region of the Texas Gulf Coast, A Compendium of Early Historical Documents…,” typed manuscript. Copy in possession of author. Weisiger, Sidney R., “Weisiger Collection,” Regional History Collection, Victoria College/University of Houston Library. SECONDARY WORKS Books Archaeology and Paleogeography of the Lower Guadalupe River/San Antonio Bay Region, Cultural Resources Investigations Along the Channel to Victoria, Calhoun and Victoria Counties, Texas, Coastal Environments, Inc., Baton Rouge, 1992. Bannon, John Francis, editor, Bolton and the Spanish Borderlands, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1968. _________________, Herbert Eugene Bolton, The Historian and the Man, 1870-1953, University of Arizona Press, Tucson, 1978. Bolton, Herbert Eugene, Athanase de Méziéres and the Louisiana Frontier, 1768-1780, The Arthur H. Clark Co., Cleveland, 1914. 27 _________________, Texas in the Middle Eighteenth Century, University of California, The University of California Publications in History, 1915. Reprint, Univeristy of Texas, Austin,1970. Brune, Gunnar, Springs of Texas; Major and Historical Springs of Texas, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1975. ____________, Major and Historical Springs of Texas, Report No. 189, Texas Water Development Board, Austin, 1975. Brinckerhoff, Sidney B. and O. B. Faulk, Lancers for the King, Phoenix, 1965. Bruseth, James E. and Toni S. Turner, From a Watery Grave, The Discovery and Excavation of LaSalle’s Shipwreck, La Belle, Texas A&M Press, College Station, 2004. Castañeda Carlos E., Our Catholic Heritage in Texas, 1519-1936. 7 vols., Von BoeckmannJones, Austin, 1936. County Maps of Texas, 2001, Texas Department of Transportation, College Station, 2001. Chipman, Donald E., Spanish Texas, 1519-1821, University of Texas Press, 1992. Cossio, David, Historia de Nuevo Leon, Monterrey, Mexico, 1925. Crimm, Ana Caroline Castillo, De León, A Tejano Family History, University of Texas Press, Austin, 2003. Dobie, J. Frank, Coronado's Children, Grosset and Dunlap, New York, 1930. ____________, The Longhorns, Branhall House, New York, 1941. ____________, The Mustangs, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1952. Faulk, Odie B., The Last Years of Spanish Texas, 1778-1821, Mouton, The Hague, 1964. _____________, Land of Many Frontiers, A History of the American Southwest, Oxford University Press, New York, 1968. Fehrenbach, T. R., Lone Star, A History of Texas and the Texans, The Macmillan Co., New York, 1968. Foster, William C., The La Salle Expedition on the Mississippi River, A Lost Manuscript of Nicolas de LaSalle, 1682, Texas State Historical Association, Austin, 2003. _____________, The La Salle Expedition to Texas, The Journal of Henri Joutel, 1684-1687, Texas State Historical Association, Austin, 1998. 28 _____________, Spanish Expeditions into Texas, 1689-1768, University of Texas Austin,1995. Press, Foster, William C. and Dorcas Baumgartner, Spanish Expeditions Through Central Texas, 16891768, self-published, Austin, 1972. Francaviglia, Richard V. From Sail to Steam, Four Centuries of Texas Maritime History, 15001900, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1998. Gibson, Charles, Spain in America, Harper and Row, New York, 1966. Gilmore, Kathleen, The Kerran Site: The Probable Site of La Salle’s Fort St. Louis, Texas Historical Commission, Report No. 24, Austin, 1973. Grimes, Roy, editor, 300 Years in Victoria County, The Victoria Advocate Publishing Co., Victoria, 1968. Hammett, A. B. J., The Empresario Don Martin de Leon, Texian Press, Waco, 1973. John, Elizabeth A. H., Storms Brewed in Other Men’s Worlds, A&M University Press, College Station, 1975. Johnson, Elmer H., The Natural Regions of Texas, Research Monograph No. 8, University of Texas, 1931. Martin, James C. and Robert Sidney Martin, Maps of Texas and the Southwest, 1513-1900, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, 1984. Meinig, D. W., Imperial Texas, An Interpretive Essay in Cultural Geography, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1969. Morris, Leopold, Pictorial History of Victoria and Victoria County, Clemens Printing Co., San Antonio, 1953. Niebuhr, Reinhold, The Irony of American History, Scribner, New York, 1952. O’Connor, Kathryn Stoner, Presidio La Bahía del Espíritu Santo de Zuniga 1721 to 1846, Von Boeckman-Jones, Austin, 1966. Poyo, Gerald, editor, Tejano Journey, 1770-1850, University of Texas Press, 1996. Reichstein, Andres V., Rise of the Lone Star, The Making of Texas, Texas A&M Press, College Station, 1989. 29 Reséndez, Andrés, Changing National Identities at the Frontier, Texas and New Mexico, 18001850, Cambridge University Press, 2004. Ricklis, Robert A., The Karankawa Indians of Texas, An Ecological Study of Cultural Tradition and Change, University of Texas, 1996. Rose, Victor Marion, History of Victoria County…, reprint, edited by Joe Petty, Jr., Book Mart, Victoria, 1961. Rouse, John E., The Criollo, Spanish Cattle in the Americas, University of Oklahoma Press, 1977. Sheffield, William J., Jr., Historic Texas Trails: How to Trace Them, Absey & Co., Inc., Spring, Texas, 2002. Shook, Robert W., Caminos y Entradas, Spanish Legacy of Victoria County and the Coastal Bend, Victoria County Heritage Department, Victoria, Texas, 2006. _____________, editor, A History of DeWitt County, by Nellie Murphree, privately published by Robert Shook, 1962. _____________, and Charles Spurlin, Victoria, A Pictorial History, The Donning Company, Norfolk, Va., 1985. ____________, compiler and editor, Vignettes of Old Victoria, Victoria County Heritage Department, Victoria, 2001. Sibley, Marilyn McAdams, Travelers in Texas, 1761-1860, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1967. Stewart, George R., American Place-Names, Oxford University Press,New York, 1970. Tennis, Cynthia L., compiler and editor, “Archaeological investigations at the last Spanish Colonial mission established on the Texas frontier: Nuestra Senora del Refugio (41RF1), Refugio County, Texas, Texas” Department of Transportation, 2002. Thonhoff, Robert, The Texas Connection with the American Revolution, Eakin Press, Austin, 1981. _____________, El Fuerte del Cíibolo, Eakin Press, Austin, 1992. _____________, editor, Forgotten Battle of the First Texas Revolution: The Battle of Medina, August 18, 1823, by Ted Schwarz, Thonhoff, Eakin Press, Austin,1985. Tijerina, Andrés, Tejanos & Texas Under the Mexican Flag, 1821-1836, Texas A&M University Press, 1994 30 Webb, Walter P., The Great Plains, Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1931. ____________, The Great Frontier, Houghton Mifflin, Boston, 1951. Weddle, Robert S., Changing Tides: Twilight and Dawn in the Spanish Sea, 1763-1803, A& M University Press, College Station, 1995. _________, The French Thorn: Rival Explorations in the Spanish Sea, 1763-1803, A & M University Press, College Station, 1991. ___________, San Juan Bautísta:Gateway to Spanish Texas, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1968. ___________, Wilderness Manhunt: The Spanish Search for La Salle, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1973. __________, The Wreck of the Belle, The Ruin of La Salle, A&M University Press, College Station, 2001. Weinstein, Richard A., et. al., Archaeology and Paleogeography of the Lower Guadalupe River/San Antonio Bay Region…, Coastal Environments, Inc., Baton Rouge, 1992. Texan Advocate, Victoria, Texas, March 2, July 5, 1848, microfilm copy, VC-UHV Library. Ximenes, Ben, Gallant Outcasts, Naylor Company, San Antonio, 1963. Zerubavel, Eviatar, Time Maps, Collective Memory and the Social Shape of the Past, University of Chicago, 2003. ARTICLES Bolton, Herbert Eugene, “The Location of La Salle’s Colony on the Gulf of Mexico,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review, September, 1915. Bulletin of the Texas Archeological Society, Austin, Published by the Society. Volume 70/1999 and several other contain research related to Victoria County. Castañeda, Carlos E., “Silent Years in Texas History,” ,” Preliminary Studies of the Texas Catholic Historical Society, Volume II, Number VIII, April, 1935. de la Teja, Jesus F., “The Camino Real, Colonial Texas’ Lifeline to the World,” A Texas Legacy: The Old San Antonio Road and the Caminos Reales, A TriCentennial History, 1691-1991, Texas StateDepartment of Highways, Austin, 1991. 31 Foik, Paul J., “Captain Don Domingo Ramons’s Diary of His Expedition into Texas in 1716,” Preliminary Studies of the Catholic Historical Society, Vol. II, April, 1933. __________, “The Martyrs of the Southwest,” Preliminary Studies of the Texas Catholic Historical Society, Volume I, Number 1, January, 1929. Fox, Anne A., “Spanish Colonial Archeology in Texas: Where We Are and Where Should We Be Going from Here?,” Bulletin of the Texas Archeological Society 70 (1999). Forrestal, Peter P., “Pena’s Diary of the Aguayo Expedition,” Preliminary Studies of the Texas Catholic Historical Society, Volume II, Number 7, January, 1935. Reprint from the Records and Studies of the United States Catholic Historical Society, Volume XXIV, October, 1934. Hackett, Charles W., editor and annotator, Pichardo’s Treatise on the Limits of Louisiana and Texas, Volumes I and II, The Bureau of Research in the Social Sciences, The University of Texas, Austin, 1931,1934. Hatcher, Mattie Austin, “The Expedition of Don Domingo Teran de Los Rios into Texas,” edited by Rev. Paul J. Foik,” Preliminary Studies of the Texas Catholic Historical Society, Volume II, Number 1, January, n.y. Hefter, Joseph, “Report on Texas Presidios, March 12, 1771,” MilitaryHistory of Texas and the Southwest, Vol. XIV, No. IV. “Journal of Stephen F. Austin on his First Trip to Texas”, Southwestern Historical Quarterly, VII, pp. 398-307. John, Elizabeth A. H., “Views from a Desk in Chihuahua: Manuel Merino’s Report on Apaches and Neighboring Nations, ca. 1804.” Translated by John Wheat, Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. 95, October, 1991. O’Donnell, Walter J., translator, “La Salle’s Occupation of Texas,” Preliminary Studies of the Texas Catholic Historical Society, Volume III, Number 2, April, 1936. Reprint from Mid-America, Vol. 18, New Series, Vol. 7, No.2. “Preliminary Report of Archaeological Testing at the Tonkawa Bluff, Victoria City Park, Victoria, Texas,” Archaeological Survey Report, No. 70. Ricklis, Robert A.,“Aboriginal Karankawan Adaption and Colonial Period, Acculturation: Archeological and Ethnohistorical Evidence,” Bulletin of the Texas Archeological Society, 63 /1992. ______________, “The Spanish Colonial Missions of Espíritu Santo (41GD1) and Nuestra Señora del Rosario (41GD2), Goliad, Texas: Exploring Patterns of 32 Ethnicity, Interaction, and Acculturation,” Bulletin of the Texas Archeological Society, 70(1999). Robbins, Elizabeth A., “The First Routes into Texas, A Review of Early Diaries,” The Old San Antonio Road and the Caminos Reales, A Tri-Centennial History, 1691-1991, Texas State Department of Highways, Austin, 1991. Steck, Rev. Francis Borgia, “Forerunners of Captain De León’s Expedition to Texas, 16701675,” Preliminary Studies of the Texas Catholic Historical Society, Volume II, Number 3 September [1932]. Reprint from Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Volume XXXVI, Number 2, July, 1932. Tous, Gabriel, “Ramon Expedition:Espinosa’s Diary of 1716,” Preliminary Studies of the Texas Catholic Historical Society, Volume 1, Number 4, April, 1930. Reprint from MidAmerica, Volume XII, Number 4, April, 1930. Walter, Tamra L., “A Preliminary Report of the 1997 TAS Field School Excavations in Area A at Mission Espiritu Santo de Zuñiga (41VT11), Victoria County, Texas,” Bulletin of the Texas Archeological Society, 70 (1999). CARTOGRAPHY AND CARTOGRAPHIC TOOLS All Topo Maps: Texas, Gage. Arnold, III, Jay Barton, A Matagorda Bay Magnetometer Survey…,Texas Antiquities Commission, Austin, 1982, Bolton, Herbert Eugene, “Map of Texas and Adjacent Regions in Eighteenth Century, 1915.” Still the most detailed and reliable map of the period for historians and ethnologists. With remarkably accurate grid references, it was a supplement to Bolton’s, momumental Texas in the Middle Eighteenth Century. Brune, Gunnar, Springs of Texas; Major and Historical Springs of Texas, University of Texas Press, Austin, 1975. ____________, Major and Historical Springs of Texas, Report No. 189, Texas Water Development Board, Austin, 1975. Jackson, Jack, “Father José Maria de Jesus Puelles and the Maps of Pichardo…,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. 91. ___________, “The 1780 Cabello Map: New Evidence That There Were Two Mission Rosarios, and a Possible Correction on the Site of El Fuerte del Cíbolo,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. CVII, No. 2, October, 2003. 33 ______________, and Robert S. Weddle, Winston DeVille, Mapping Texas and the Gulf Coast, The Contributions of Saint-Denis, Olivan, and Le Maire, Texas A and M Press, College Station, 1990. ______________, Shooting the Sun: Cartographic Results of Military Activities in Texas, 1689- 1829, Book Club of Texas, Austin, 1998. McGraw, A. Joaquin and James E. Corbin, A Review Essay of “Spanish Expeditions into Texas,” by William C. Foster (1995), “Response to a Review Essay of “Spanish Expeditions into Texas, 1689-1768,” Bulletin of the Texas Archeological Society, 70(1999). Martin, Robert S. “Maps of an Empresario: Austin’s Contribution to the Cartography of Texas,” Southwestern Historical Quarterly, vol. 85. Maps of Gulf Intracoastal Waterway, Texas, Sabine River to the Rio Grande..., Department of the Army, District Engineer, Galveston District, Corps of Engineers, Galveston, Texas, June, 1966. Reinhartz, Dennis, and Charles C. Colley, The Mapping of the American Southwest, Texas A and M Univerisity, College Station, 1987. Texas State Library Maps. Each of the following maps was consulted for the information and characteristics inherent in each, including errors which are often important. Superimposed on USGS quadrants and adjusted for transparency and proportion, they are extremely valuable in establishing historical features on current topographic and highway maps. Digitized copies of these maps are available, for educational purposes only, from the Victoria County Heritage Department or the author courtesy James Woodrick, Austin, Texas: 0023a, 0055, 0378, 0382, 0399, 0399, 0424, 0445a, 0906, 0908, 0917, 0940, 0942, 1012, 1021, 1032, 1032, 1050, 1201, 1446, 1449, 1480,1514, 1590, 1594, 1600, 1607b, 1647,1924, 1997, 1997a, 2730, 3938, 409c, 409A, 416, 421, 25 Topographical Map of the Country between San Antonio and Colorado Rivers in the State of Texas, A.D. 1864, Old Military Records Division, National Archives, Washington, D. C. This is one of the most significant documents available for Texas history. Drawn by a Federal officer under orders to note all homesteads, roads—many of which follow early Spanish trails— vegetation, supplies, and other details necessary for the occupation of Texas during the Civil War. In its original format, white on back or negative, the many segments of the entire document were inverted, stitched, and assembled by counties by Robert W. Shook, Ph.D., Historical Consultant, Victoria County Heritage Office, where the segments are available for educational purposes only. Topo USA, De Lorme, version 5.0 34