CREDIT:

2.0

Continuing Education

EARN CE CREDIT FOR THIS ACTIVITY AT WWW.DRUGTOPICS.COM

AN ONGOING CE PROGRAM OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CONNECTICUT

SCHOOL OF PHARMACY AND DRUG TOPICS

educationaL oBJectiVeS

Goal: To assist pharmacists and pharmacy

technicians in understanding the impact of

electronic health record (EHR) systems on

pharmacy practice, as the use of EHR systems

continues to increase.

After participating in this activity, pharmacists

will be able to:

● Summarize the impact on pharmacy practice

of the new HHS rules governing the use of

electronic health record (EHR) systems.

● Identify the ways in which EHR systems will

increase the efficiency of pharmacy practice

with respect to continuity of care, formulary

checks, drug-to-drug and drug-to-allergy

interactions, and medication reconciliation.

● Summarize the challenges pharmacists face

as EHR systems come into increasingly

wider use.

● Apply the process of pharmacists using

EHRs to case scenarios

The University of Connecticut School of

Pharmacy is accredited by the Accreditation

Council for Pharmacy Education as a provider

of continuing pharmacy education.

Pharmacists are eligible to participate in both the

knowledge-based and application-based activities,

and will receive up to 0.2 CEUs (2 contact hours) for

completing the activity/activities, passing the quiz/

quizzes with a grade of 70% or better, and completing

an online evaluation. Statements of credit are available

via the online system.

Pharmacy technicians are eligible to participate in

the knowledge-based activity and will receive 0.1

CEU (1 contact hour) for completing the activity,

passing the quiz with a grade of 70% or better, and

completing the online evaluation. Statements of

credit are available via the online system.

ACPE #0009-9999-12-007-H04-P/T (Part 1)

ACPE #0009-9999-12-008-HO4-P (Part 2)

Grant Funding: Funding for this activity was provided by:

Cephalon; Endo Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Purdue Pharma L.P.

Activity Fee: There is no fee for these activities.

Initial release date: 4/10/2012

Expiration date: 4/10/2014

To obtain immediate CPE credit, take the test online

at www.drugtopics.com/cpe. Just click on the link you

find under Free CPE Activities, which will take you to

the CPE site. For first-time users, please complete the

registration page. For those already registered, log

in, find, and click on this lesson. Test results will be

displayed immediately. Complete the evaluation form

and you will receive a printable statement of credit by

e-mail, showing your earned CPE credit.

For questions concerning the online CPE activities,

e-mail: cpehelp@advanstar.com.

the impact of electronic

health records on

pharmacy practice

Rachelle Spiro, RPh, FASCP

DIRECTOR, PHARMACY E-HEALTH INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY COLLABORATIVE, ALEXANDRIA, VA; CEO

AND PRESIDENT, SPIRO CONSULTING, INC., LAS VEGAS, NV

W

ith the American Recovery

and Reinvestment Act (ARRA),

which was signed into law in

2009, Congress set ambitious goals for

the nation to integrate information technology into healthcare delivery.1,2 A segment

of ARRA, the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act

(HITECH), authorized incentive payments

through Medicare and Medicaid to providers that use certified electronic health

records (EHRs) to achieve specified improvements in healthcare delivery and

implement a nationwide EHR system by

2014.3

At the bill’s enactment in 2009, only

11.9% of hospitals made any use of EHRs,

with only 2% meeting what would be stage

1 meaningful use criteria.4 Only 21.8% of

office-based physicians had basic electronic

systems and only 6.9% had fully functional

electronic systems.5 The U.S. Department

of Health & Human Services (HHS) finalized the meaningful use criteria for the first

2 years of the 3-stage incentive program

in mid 2010.5 The bill’s health information

technology (HIT) component followed the

earlier Office of the National Coordinator

(ONC) for Health Information Technology

created by presidential executive order in

Faculty: Rachelle Spiro, RPh, FaScP

Ms. Spiro is Director, Pharmacy e-Health Information Technology Collaborative, Alexandria, VA, and CEO

and President, Spiro Consulting, Inc., Las Vegas, NV. Editorial assistance was provided by Deborah

Kaplan. Ms. Kaplan’s revisions were reviewed and approved by Ms. Spiro.

Faculty Disclosure: Ms. Spiro has no actual or potential conflict of interest associated with this article.

Disclosure of Discussions of Off-Label and Investigational Uses of Drugs: This activity may contain discussion

of unlabeled/unapproved use of drugs. The content and views presented in this educational program are

those of the faculty and do not necessarily represent those of Drug Topics or University of Connecticut

School of Pharmacy. Please refer to the official prescribing information for each product for discussion

of approved indications, contraindications, and warnings.

46

Drug topics

April 2012

DrugTopics .c om

GETTY IMAGES/PHOTODISC/MACIEJ FROLOW

After participating in this activity, pharmacy

technicians will be able to:

● Recognize the impact on pharmacy practice

of the new HHS rules governing the use of

EHR systems.

● Identify the ways in which EHR systems will

increase the efficiency of pharmacy practice

with respect to continuity of care, formulary

checks, drug-to-drug and drug-to-allergy

interactions, and medication reconciliation.

● Recognize the challenges pharmacists face as

EHR systems come into increasingly wider use.

continuing education

glossary of terms

ACO

ADEs

ARRA

CAH

CCD

CDS

CMR

CMS

CPOE

CPT

DEA

EHR

EMR

EPCS

ePHR

Accountable care

organization

Adverse drug events

American Recovery and

Reinvestment Act

Critical access hospital

Continuity-of-care document

Clinical decision support

Comprehensive medication

review

Center for Medicare and

Medicaid Services

Computerized provider order

entry

Current procedural

terminology

Drug Enforcement Agency

Electronic health record

Electronic medical record

Electronic prescribing for

controlled substances

Electronic personal health

record

U.S. Department of Health &

Human Services

Health Insurance Portability

and Accountability Act

Health Information

Technology for Economic

Clinical Health

Health information exchange

Health information

technology

Health Level Seven

Long-term care

Medical therapy management

Office of the National

Coordinator

Primary care physician (or

provider)

Personal health record

Pharmacy management

system

Pharmacy/pharmacist

provider electronic health

record

Abstract

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 set ambitious goals for

the nation to integrate information technology into healthcare delivery. The

Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act segment of

the bill provides incentives for Medicare and Medicaid providers to use certified

electronic health records (EHRs) to achieve specified improvements in healthcare

and implement a nationwide EHR system by 2014. Meaningful use criteria

are being promulgated in 3 stages. Medicare and Medicaid incentive payments

will total $27 billion over a 10-year period with $17 billion designated for

EHR development. Pharmacists will not receive direct funding or incentives but

pharmacy schools may receive grants for incorporating electronic personal health

technology into clinical education. The nation’s goal for EHRs is to reduce costs

through less paperwork, improved safety, and reduced duplication of testing, and

improve health by gathering a patient’s entire health information in a single

location. Electronic connectivity through e-prescribing—the paperless, real-time

transmission of standardized prescription data among prescribers, pharmacies,

and payers—places pharmacists squarely within the healthcare technology team.

The Pharmacy e-Health Information Technology (HIT) Collaborative, a group of

9 national pharmacy organizations and associate members, advocates integrating

the pharmacist’s role of providing patient care services into the national HIT

interoperable framework. The greatest challenge that pharmacists face in the new

era of electronic health information is to be recognized by Medicare and Medicaid

as eligible providers of medication-related patient care services and as meaningful

use contributors to electronic health information.

The primary goals of improving the nation’s HIT infrastructure are to:

• Ensure protection and privacy of

HIPAA

healthcare information;

• Improve patient care by reducing

HITECH

medical errors;

• Reduce costs by removing administrative

barriers that result in duplicative claims

HIE

and services; and

HIT

• Improve coordination of care among

healthcare providers.

HL7

To achieve these goals, as much as $27

LTC

billion over 10 years was designated in MediMTM

care and Medicaid incentive payments for

ONC

eligible providers who use EHRs and demonstrate “meaningful use” of HIT.3 In addition,

HIT systems have to be certified as meetPCP

ing certain technologic standards. A total of

$19 billion was designated to implement HIT

PHR

regional health information exchange (HIE)

PMS

networks.1,3 Of this amount, $17 billion includes the incentive payments to physicians

PP-EHR

and hospitals to develop personal healthcare

records by 2014. The remaining $2 billion

is allocated to developing and improving the

2004.6 ONC works with the Center for Medi- nation’s HIT infrastructure.1,3

care and Medicaid Services (CMS) to set the

The Congressional Research Service

policies relevant to incentive payments under expects that the incentives will promote

meaningful use requirements.7

EHR use in 70% of hospitals and 90% of

HHS

DrugTopics .c om

physician offices by 2019.8 The Congressional Budget Office has projected that

HITECH will reduce federal and private sector spending on health services during the

next decade by tens of billions of dollars

by increasing efficiency.9 By October 2011,

$1.2 billion incentives had been paid.7 Preliminary data for 2011 show the use of

EHRs growing, but the goals for 2019 are

considered ambitious.10

Pharmacists will not receive direct funding or incentives for adopting electronic

medical record technology. Pharmacy

schools, however, are included among the

list of approved graduate schools that may

receive grants for incorporating electronic

personal health technology into clinical education.1 Stage 1 of the 3-stage meaningful

use program launched in 2010 focuses

on the integration of electronic healthcare

among patients, providers, government

agencies, and insurers. There are 25 Medicare and Medicaid meaningful use criteria,

of which eligible professionals must adopt

15 professional core objectives to qualify

for the incentives (Table 1, page 48).7

Eligible professionals can receive as much

as $44,000 over a 5-year period through

Medicare. For Medicaid, eligible professionApril 2012

Drug topics

47

eLectRonic HeaLtH RecoRdS

Continuing Education

TABLE 1

TABLE 2

proFessional core oBJecTives required For Medicare and

Medicaid incenTives

1. Use CPOE

2. Implement drug-drug and drug-allergy interaction checks

3. Maintain an up-to-date problem list of current and active diagnoses

4. Generate and transmit permissible prescriptions electronically

5. Maintain an active medications list

6. Maintain an active medications allergy list

7. Record demographics (preferred language, gender, race, ethnicity, date of birth)

8. Record vital signs and chart changes (height, weight, blood pressure, BMI, growth charts for

children aged 2 to 20 years)

9. Record smoking status for patients aged 13 years or older

10. Report ambulatory clinical quality measures

11. Implement clinical decision support rule as determined by the eligible professional

12. Provide patients with an electronic copy of their health information

13. Provide clinical summaries for patients for each office visit

14. Capability to exchange key clinical information electronically (eg, problem list, medication list,

diagnostic test results) among care providers and patient-authorized entities

15. Protect electronic health information by use of certified technology

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CPOE, computerized provider order entry.

Source: Ref 7

als can receive as much as $63,750 over 6

years.11 The first incentives were scheduled

for October 2011 based on 2010 performance. By 2015, physicians who are not

using certified EHRs could be penalized by

Medicare and Medicaid.12

In February 2012, federal officials released the stage 2 guidelines for meaningful use.11 The proposed stage 2 rules,

which are undergoing review at this time,

require physicians and hospitals to significantly increase their use of electronic

health information, as well as better engage patients and improve the transferability of records.13 The meaningful use

approach requires identification of standards structured in uniform ways so that

EHR systems can deliver the information

just as commonly used automated teller

machines depend on uniformly structured

data.7 If data cannot be captured uniformly, electronic systems cannot communicate or are not interoperable.14,15 Stage 2

meaningful usage will require that at least

60% of patients have their medications

and laboratory tests ordered electronically

instead of the 30% required by the stage

1 regulations. The government is placing

48

Drug topics

April 2012

emphasis on having electronic systems

that are interoperable or can communicate with each other. Thus, the 2012

stage 2 rules require that systems be able

to transfer patient information including a

patient’s notes, medications list, allergies,

and diagnostic and laboratory test results

across platforms. The information should

also be available to patients to view their

records online as well as download and

transfer information. Additionally, patients

should be able to communicate with their

physicians through a secure, online system or patient portal.13

integrating pharmacy

health information in

u.s. healthcare

Often the terms electronic medical record

(EMR) and electronic health record (EHR)

technology are used interchangeably.

EHR is defined as “an electronic record of

health-related information on an individual

that is created, gathered, managed, and

consulted by authorized healthcare clinicians and staff.”11 The personal health

record (PHR) is defined as “an electronic

record of individually identifiable health

BeneFiTs oF MeaningFul

use oF ehrs

By adopting EHRs in a meaningful

way, healthcare providers can:

» Know more about their patients.

Information in EHRs can be used to

coordinate and improve the quality

of patient care.

» Make better decisions. With more

comprehensive information readily

and securely available, healthcare

providers will have the information

they need about treatments and

conditions – even best practices for

patient populations – when making

treatment decisions.

» Save money. EHRs require an

initial investment of time and

money, but healthcare providers

who have implemented them have

reported reductions in the amount

of time spent locating paper files,

transcribing, and spending time on

the phone with labs or pharmacies;

more accurate coding; and

reductions in reporting burden.

Abbreviations: EHR, electronic health record.

Source: Ref 11

information on an individual that can be

drawn from multiple sources and that is

managed, shared, and controlled by and

for the individual.”11 The EHR differs from

the EMR in that it contains information that

is shared among healthcare providers using

interoperability standards.6 The EHR is an

individual patient’s medical record in digital,

interoperable format that includes the patient’s demographics, medical history, allergies, medications, progress notes, laboratory and diagnostic test results, scans, and

advance directives. It contains data from

many sources and can communicate with

various health and medical entities.6

An electronic tool that is initiated by the

patient is the electronic personal health record (ePHR).6 In contrast to the EHR, which

is generated by healthcare providers, the

ePHR can be generated by physicians, patients, hospitals, pharmacies, and other

sources but is managed by the patient.11

Ultimately, it is the ePHR that healthcare

analysts consider the best electronic tool

to address concerns about privacy issues

DrugTopics .c om

continuing education

with electronic health information.16

The nation’s goal for EHRs is to reduce

costs through less paperwork, improved safety, reduced duplication of testing, and improve

health by gathering a patient’s entire health

information in a single location. Additionally,

EHRs can compute the information. For example, a qualified EHR not only contains a

record of a patient’s medications or allergies

but also automatically checks for problems

whenever a new medication is prescribed and

alerts the clinician to potential conflicts.7 The

meaningful use of EHRs and HIEs can help

clinicians provide higher quality and safer care

for their patients (Table 2, page 48).11

For the purposes of the Medicare and

Medicaid incentive programs, eligible professionals, eligible hospitals, and critical access hospitals (CAHs) must use certified

EHR technology. The federal government

has established certification standards

consistent with requirements for meaningful use.17 Certified EHR technology gives

assurance to purchasers and other users

that an EHR system or module offers the

necessary technologic capability, functionality, and security to help them meet the

meaningful use criteria. Certification also

helps providers and patients be confident

that the electronic HIT products and systems they use are secure, can maintain

data confidentially, and can work with other

systems to share information.11

The PP-EHR is the pharmacy/pharmacist provider electronic health record. The

Pharmacy e-HIT Collaborative, a group of

9 national pharmacy organizations and associate members, continues to work with

national EHR certification organizations and

pharmacy system vendors to assure that

the PP-EHR functionality is adopted with

the development of certification criteria to

meet the meaningful use of EHR concepts

related to pharmacy services.18 Members

of the Collaborative were involved in working

with a joint Health Level Seven (HL7) and National Council for Prescription Drug Programs

(NCPDP) work group in the development of

the PP-EHR functional profile, an HL7 functional profile that represents “the functionality required and desired for a care setting or

application, or reflect the functionality incorporated in a vendor’s EHR system.”18

To elaborate further, from a standards

perspective, all EHRs follow HL7 functionalDrugTopics .c om

TABLE 3

inTerneT resources For

e-prescriBing

www.cms.hhs.gov/eprescribing

www.ehealthinitiative.org

www.himss.org

www.nationalerx.com

www.surescripts.com

ity. Each provider type can adopt a standard

HL7 EHR functional profile (e.g., pharmacists can adopt a pharmacist EHR specific

for documentation of pharmacist-provided

patient care information). These are different from claims-based standards used by

pharmacists for billing prescriptions such

as NCPDP version D.0.

Each provider

type can adopt a

standard HL7 EHR

functional profile.

e-prescribing: use,

benefits, challenges

Electronic connectivity through electronic

(e)-prescribing—the paperless, real-time

transmission of standardized prescription

data among prescribers, pharmacies, and

payers—places pharmacists squarely

within the healthcare technology team.19

E-prescribing communicates medications

history, new prescriptions, changes, refills,

and other prescription data. In 2000, the

Institute of Medicine recommended that

e-prescribing be in place for all prescriptions by 2010. Although short of that goal,

by 2010 more than 300 million prescrip-

tions were being routed electronically.20

More than half of office-based physicians

in the United States are reported to use

e-prescribing.21 The number of pharmacies connected electronically also continues to increase. According to Surescripts,

91% of community pharmacies in the

United States in 2010 were connected

for prescription routing compared with

76% in 2008. For independently owned

pharmacies, 73% were connected in 2010

compared with 46% in 2008.20

A national survey reported that community pharmacists and technicians were generally satisfied with e-prescribing because

of the improved legibility of electronic prescriptions and more efficient processing.22

Pharmacists in the survey also noted that

refill prescriptions and new prescriptions

required less staff time. Prescribing errors

were the most commonly cited negative

feature of e-prescribing, particularly those

which called for a wrong drug or gave erroneous directions.22

In more than 100 interviews with physician practices and pharmacies nationwide

this past year, researchers at the Center

for Studying Health System Change noted

flaws and inconsistencies concentrated in

3 critical areas in e-prescriptions. These include prescription renewals, connectivity between physician offices and mail-order pharmacies, and manual entry of prescription

information by pharmacists.23 Moreover,

pharmacies and physicians report duplicate or conflicting messages. Significantly,

short-cut features fail to aid that message

and communication fields that complete

automatically often require follow-up calls

or manual entry by pharmacists to clarify a

physician’s orders, verify quantities and sig

codes (pharmacy terminology), or provide

patient-friendly instructions.23

One barrier to e-prescribing—maintenance of a parallel paper system for controlled substances—essentially ended

pause&ponder

according to a national survey, community pharmacists

and technicians were generally satisfied with

e-prescribing because of the improved legibility of

electronic prescriptions. However, are you still following

up frequently with physicians to clarify orders?

April 2012

Drug topics

49

eLectRonic HeaLtH RecoRdS

Continuing Education

TABLE 4

TABLE 5

10 goals For pharMacy inTegraTion in healThcare sysTeM

vocaBulary sTandards

For elecTronic healTh

inForMaTion (code seTs)

1. Ensure HIT supports pharmacists in healthcare service delivery

2. Achieve integration of clinical data with electronic prescription (e-prescribing) information

3. Advocate pharmacist recognition in existing programs and policies

4. Ensure HIT infrastructure includes and supports MTM services

5. Integrate pharmacist-delivered immunizations into the EHR

6. Achieve recognition of pharmacists as meaningful users of EHR quality measures

7. Advance system vendor EHR certification

8. Promote pharmacist adoption and use of HIT and EHRs

9. Achieve integration of pharmacies and pharmacists into health information exchanges

10. Establish the value and effective use of HIT solutions by pharmacists

Abbreviations: EHR, electronic health record; HIT, health information technology; MTM, medication therapy management.

Source: Ref 18

when the prohibition against e-prescribing

for controlled substances (EPCS) was

amended in 2010 when the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) issued new

regulations that provide practitioners with

the option of EPCS. The revised DEA regulations also permit pharmacies to receive,

dispense, and archive electronic prescriptions.24 It is important to note, however, that

not all states have authorized EPCS, particularly Schedule II controlled substances.

For more information on e-prescribing,

please consult the websites listed in Table

3, page 49.

EHr systems increase

efficiency of pharmacy

practice, improving patient

outcomes

The Pharmacy e-HIT Collaborative advocates integrating the pharmacist’s role of

providing patient care services into the

national HIT interoperable framework.18

The Collaborative has issued a 10-goal

plan entitled “The Roadmap for Pharmacy

Health Information Technology Integration in U.S. Health Care” to promote the

inclusion of pharmacists as recognized

providers of the CMS HIT strategy (Table

4).18 The Collaborative states that pharmacists have an important role in optimal

therapeutic outcomes and safe and costeffective medication use and that the clinical services of pharmacists are a critical

component of the U.S. healthcare system.

For example, the ability to report adverse

drug events (ADEs) within the EHR and integrate reports on a national level allows

for tracking ADEs and early identification

of potentially dangerous medication side

effects.18

Medication therapy management (MTM),

which can optimize therapeutic outcomes

for individual patients, is a unique area of

contribution for pharmacy.25 Pharmacists

are key information providers in MTM, including medication reconciliation and care

transitions, medication adherence, medication monitoring, medication safety, and

evaluation of medication errors.18

MTM core elements include: medication

therapy review; personal medication record;

medication-related action plan; intervention

and referral; and documentation.18 Sharing

components of MTM between providers by

means of the continuity-of-care document

(CCD) demonstrates the value of meaningful use of the EHR by pharmacists. The

pause&ponder

Pharmacists have an important role in optimal

therapeutic outcomes and safe and cost-effective

medication use. are pharmacists in your practice setting

utilized appropriately to help during transitions of care?

50

Drug topics

April 2012

Codes sets are used for encoding

data elements, such as medical

concepts, diagnoses, or procedures.

(Nonmedical code sets, also known

as administrative code sets, encode

nonmedical data, including ZIP code,

state abbreviations.)

» Clinical terms. Systematized

Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical

Terms (SNOMED CT)

» Diagnosis codes: ICD-10 (coding

for all providers covered by the

Health Insurance Portability and

Accountability Act (HIPAA)

» Laboratory test results. Logical

Observation Identifiers Names and

Codes (LOINC)

» Medications. RxNorm, a standardized

nomenclature for clinical drugs and

drug delivery devices, is produced by

the National Library of Medicine.

» Immunizations. Code set for

vaccines administered (CVX)

Source: Ref 7

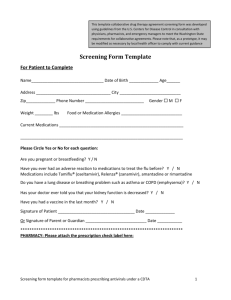

MTM core elements service model illustrates how pharmacists can interface with

the patient care process (Figure 1, page

51). The process begins with medication

therapy review. The patient interview is

conducted and a database with patient

information is created. Medications are reviewed for indication, effectiveness, safety,

and adherence. A list of medication-related problems is generated and prioritized,

generating a MTM plan. Intervention and/

or referrals involve patient, physician, pharmacist, or other healthcare professionals.

It is estimated that more than half of

medication errors occur during patient care

transitions.26 The proposed 2012 stage 2

meaningful use objectives require that medication reconciliation be conducted by 65%

of care transitions by the receiving providers.18 Therefore, medication reconciliation

at transitions of care should be part of the

EHR documentation process in all practice

settings.18 At a minimum the following information should be communicated electronically to pharmacists at transitions of care:

medications list, medical condition, and allerDrugTopics .c om

continuing education

FIGURE 1

The Medication Therapy Management Core Elements Service Model

The diagram depicts how the MTM Core Elements (❖) interface with the patient care process to create an MTM Service Model.

❖

MEDICATION THERAPY REVIEW

❖

INTERVENTION AND/OR REFERRAL

Interview patient and create

a database with patient

information

Possible referral of patient

to physician, another pharmacist or other healthcare

professional

Review medications for indication, effectiveness, safety, and

adherence

Interventions directly with patients

List medication-related

problem(s) & Prioritize

Create a plan

❖

Implement

Plan

Interventions via collaboration

Create/Communicate

PERSONAL

MEDICATION

RECORD (PMR)

Create/Communicate

MEDICATIONRELATED ACTION

PLAN (MAP)

❖

Complete/Communicate

& Conduct

Physician and other healthcare

professionals

❖

DOCUMENTATION &

FOLLOW-UP

Used with permission. Copyright © 2008 by the American Pharmacists Association and the National Association of Chain Drug Stores Foundation. All rights reserved.

Source: Ref 18

gies. For optimal medication management,

pharmacists should receive the full content

of the CCD including laboratory values, prescriber information, and medication history.18

The process of medication reconciliation

includes comparing a patient’s medication

orders to all the medications that the patient has been taking, and it should be undertaken at every transition of care in which

new medications are ordered or existing orders are rewritten. The principles of medication reconciliation must be incorporated

into EHR systems, and to ensure that it is

done appropriately, professional guidelines

should be implemented and overseen by

pharmacists.18

Medication adherence is a basic component of comprehensive MTM. The Collaborative states that with access to electronic

health information from the CCD, pharmacists and other providers can better assess medication adherence outcomes and

address medication-related problems such

as drug-drug and drug-allergy interactions.18

Further, CMS recognizes the role of

pharmacists as MTM providers under the

Medicare Part D program. This includes

pharmacist-provided education counseling

for beneficiaries, compliance programs

such as refill reminders and special packaging, and detection of adverse events and

patterns of prescription drug overuse and

DrugTopics .c om

under use. Because of their professional

knowledge and capabilities, pharmacists

should be recognized as meaningful users

of the EHR in matters of Medicare Part D.18

Challenges pharmacists

face as EHR systems come

into increasingly wider use

The greatest challenge that pharmacists

face in the new era of electronic health

information is to be recognized as eligible

providers by Medicare and Medicaid and

by accountable care organizations (ACOs)

of medication-related patient care services

and as meaningful users and contributors

to EHR. As a first step, the Collaborative

of pharmacy organizations urges that

e-prescribing be adopted in all practice

settings. Further, pharmacists should

exchange clinical information with each

other and other healthcare providers in a

bidirectional manner. Pharmacists need

to work with pharmacy system vendors to

set communications standards and build

awareness of the standardized certified

pharmacist EHR functional profile.18 Such

alliances support meaningful use and enable pharmacies to support improvements

in care, safety, cost, and health outcomes.

A recent example of such collaboration

is the announcement by Walgreens that all

of the 7,800 Walgreens and Duane Reade

pharmacies and 350 Take Care Clinics

nationwide will use the Surescripts clinical

interoperability network to deliver immunization records to the patient’s primary care

provider.27 Currently, records such as inpharmacy immunizations have been sent

to physicians by fax or traditional mail. By

using the electronic network, pharmacists

and pharmacy healthcare providers contribute to the compilation of more complete

medical histories for their patients.27

In the 2011-2012 flu season, more

than 27,000 certified immunizing pharmacists, nurse practitioners, and physician

assistants at Walgreens and Duane Reade

pharmacies and Take Care Clinics administered more than 5.5 million immunizations.

Surescripts will use a standard format to

capture immunization details and send

the record to the patient’s primary care

physician in whatever form the provider is

able to receive it, electronically or via fax

or mail. Physicians using a Surescriptscertified EHR, however, will have the option of receiving immunization records via

the Surescripts Clinical Interoperability

Network.27

The pharmacy profession is actively

contributing to quality patient care through

MTM services that identify and prevent

medication-related problems, improve medication use, and optimize individual patient

April 2012

Drug topics

51

eLectRonic HeaLtH RecoRdS

Continuing Education

therapeutic outcomes. As MTM programs

continue to expand within the healthcare

system, however, the lack of standardization for documentation and billing of MTM

services is limiting its use and is a barrier

to MTM service delivery for patients.28 To

allow for the interchange of electronic information, pharmacists need to champion

e-prescribing standards and use current

procedural terminology (CPT) billing codes

for MTM services.6 Table 5 (page 50) identifies common code sets.7

Pharmacy organizations large and small

must recognize that implementing HIT requires designing workflow management to

overcome the disruption that arrives with

new technologic practices.6 The negative

impact of HIT implementation on care processes, workflow, and safety is known and

was the subject of a Joint Commission alert

in 2008.29 Stresses placed on healthcare

providers and staff when workflow is compromised by new technology systems can

produce technology-related adverse events.6

The USP MEDMARX for 2006 reported that

one-quarter of more than 175,000 medication errors involved some aspect of computer technology.30 For example, an actual increased risk for HIT-related medication errors

was reported in a study of a computerized

provider order entry (CPOE) system.31 Examples included fragmented CPOE displays

that conveyed erroneous information about

patient medications and orders.

To evaluate the effects of CPOE with

clinical decision support (CDS) on ADEs,

researchers reviewed the medical literature

for original investigations, randomized and

nonrandomized clinical trials, and observational studies.32 They found studies that

identified the type of computer system

used, drug categories evaluated, types of

ADEs measured, and clinical outcomes.

Of the 543 citations identified, 10 studies

met inclusion criteria. These studies were

grouped into categories based on their setDownload or take the test online at

www.drugtopics.com/cpe

once there, click on the link below

Free cpE Activities

52

Drug topics

April 2012

ting: hospital or ambulatory; no studies

related to the long-term care setting were

identified. In 5 (50%) of the 10 studies,

CPOE with CDS contributed to a statistically significant decrease in ADEs (P ≤.05).

Four studies (40%) reported a nonstatistically significant reduction in ADE rates, and

1 study (10%) demonstrated no change in

ADE rates.32

At a study at a 700-bed academic medical center in Chicago, clinical staff pharmacists saved all orders that contained a prescribing error for a week in early 2002.33

The investigators classified drug class,

error type, proximal cause, phase of hospitalization, and potential for patient harm

and rated the likelihood that CPOE would

have prevented the prescribing error. A total

of 1,111 prescribing errors were identified

(62.4 errors per 1,000 medication orders),

most occurring on admission (64%). Of

these, 30.8% were rated clinically significant and were most frequently related to

anti-infective medication orders, incorrect

dose, and medication knowledge deficiency. Of all verified prescribing errors, 64.4%

were rated as likely to be prevented with

CPOE (including 43% of potentially harmful

errors), 13.2% unlikely to be prevented with

CPOE, and 22.4% possibly prevented with

CPOE depending on specific CPOE system

characteristics. The investigators concluded

that although prescribing errors are common in the hospital setting, CPOE systems

could improve practitioner prescribing. The

design and implementation of a CPOE system should focus on errors with the greatest potential for patient harm. Pharmacist

involvement, in addition to a CPOE system

with advanced CDS, is vital for medication

safety.33

conclusion

As members of the electronically connected healthcare team, pharmacists

have the unique knowledge, expertise,

and responsibility to assume a significant

role in electronic health information. And

as governments and the healthcare community develop strategic plans for the

widespread adoption of HIT, pharmacists

must use their knowledge of information

systems and the medication use process

to ensure that the new technologies lead

to better patient outcomes.

References

1. American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.

http://www.recovery.gov/About/Pages/The_Act.

aspx#act. Accessed March 20, 2012.

2. Gold MR, McLaughlin CG, Devers KJ, Berenson

RA, Bovbjerg RR. Obtaining providers’ ‘buy-in’ and

establishing effective means of information exchange

will be critical to HITECH’s success. Health Aff

(Millwood). 2012;31(3):514–526.

3. Health Information Technology for Economic and

Clinical Health (HITECH) Act, Title XIII of Division A and

Title IV of Division B of the American Recovery and

Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA), Pub. L. No. 1115 (Feb. 17, 2009), codified at 42 U.S.C. §§300jj et

seq.; §§17901 et seq. Updated September 28, 2011.

http://healthit.hhs.gov/portal/server.pt/community/

healthit_hhs_gov__regulations_and_guidance/1496.

Accessed March 20, 2012.

4. Jha AK, DesRoches CM, Kralovec PD, Joshi MS. A progress

report on electronic health records in US hospitals. Health

Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(10):1951–1957.

5. Hsiao C-J, Hing E, Socey TC, Cai B. Electronic medical

record/electronic health record systems of office-based

physicians: United States, 2009 and preliminary 2010

state estimates. Health E-Stats. Hyattsville, MD: National

Center for Health Statistics. 2010. http://www.cdc.

gov/nchs/data/hestat/emr_ehr_09/emr_ehr_09.pdf.

Accessed March 20, 2012.

6. Webster L, Spiro RF. A new world for pharmacy.

Pharmacy Today. 2010;16:32–44.

7. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS EMR

meaningful use overview. Baltimore, MD: CMS. Last

modified December 8, 2011. https://www.cms.gov/

EHRIncentivePrograms/01_Overview.asp#TopOfPage.

Accessed March 20, 2012.

8. Redhead CS. The Health Information Technology for

Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act: CRS report

for Congress. Washington, DC: Congressional Research

Service; February 23, 2009.

9. Stark P. Congressional intent for the HITECH act. Am J

Manag Care. 2010;16(12 Suppl HIT):SP24-SP28.

10. Hsiao C-J, Hing E, Socey TC, Cai B. Electronic health record

systems and intent to apply for meaningful use incentives

among office-based physician practices, United States

2001–2011. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health

Statistics; 2011, Data Brief No. 79. Revised February 8,

2012. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/DB79.pdf.

Accessed March 20, 2012.

11. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Office

of the National Coordinator for Health Information

Technology. Health IT. Washington, DC: HHS. Updated

February 18, 2011. http://www.healthit.hhs.gov/.

Accessed March 20, 2012.

12. Healthcare Finance News. Eligible provider

meaningful use criteria. December 31, 2009. www.

healthcarefinancenews.com/news/eligible-providermeaningful-use-criteria. Accessed March 20, 2012.

13. Torres C. Electronic health records program advances

to ‘stage 2.’ Capsules, KHN blog. Kaiser Health News,

February 24, 2012. http://capsules.kaiserhealthnews.

org/index.php/2012/02/health-it-coordinator-releaseof- stage-2-guidelines-a-push-ahead/. Accessed March

20, 2012.

14. Diamond CC, Shirky C. Health information technology:

A few years of magical thinking? Health Aff (Millwood).

2008;27(5):383–390.

15. Hammond WE, Bailey C, Boucher P, Spohr M, Whitaker

P. Connecting information to improve health. Health Aff

(Millwood). 2010;29(2):284–288.

16. Healthcare Information and Management Systems

Society. HIMSS’ PHR and ePHR definition and position

statement. http://www.himss.org/asp/topics_news_item.

asp?cid=67200&tid=34. Accessed March 20, 2012.

17. Bean C. Certification programs. Presentation at: Office

of the National Coordinator for Health Information

DrugTopics .c om

continuing education

Technology Annual Meeting; Washington, DC,

November 16–18, 2011.

18.Pharmacy e-Health Information Technology

Collaborative. The Roadmap for Pharmacy Health

Information Technology Integration in U.S. Health

Care. http://www.pharmacyhit.org/pdfs/11-392_

RoadMapFinal_singlepages.pdf. Accesssed March

20, 2012.

19.Spiro RF, Gagnon JP, Knutson AR. Role of health

information technology in optimizing pharmacists’

patient care services. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003).

2010;50(1):4–8.

20.Surescripts. The National Progress Report on

E-Prescribing and Interoperable Healthcare 2010.

http://www.surescripts.com/pdfs/national-progressreport.pdf. Accessed March 20, 2012.

21.Surescripts. Surescripts announces that majority

of doctors in U.S. now use e-prescribing. http://

www.surescripts.com/news-and-events/pressreleases/2011/november/0911_safer x.aspx.

Accessed March 20, 2012.

22.Rupp MT, Warholak TL. Evaluation of e-prescribing

in chain community pharmacy: Best-practice

recommendations. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003).

2008;48(3):364–370.

23.Enderle L. The pitfalls of e-prescribing. Pharmacy Times.

November 29, 2011. http://www.pharmacytimes.com/

web-exclusives/The-Pitfalls-of-E-Prescribing. Accessed

March 20, 2012.

24.U.S. Department of Justice. Drug Enforcement

Administration. Office of Diversion Control. Electronic

prescriptions for controlled substances clarification.

http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/fed_regs/

notices/2011/fr1019.htm. Accessed March 20, 2012.

25.Bluml BM. Definition of medication therapy

management: Development of professionwide

c o n s e n s u s . J A m P ha r m A s s o c (20 0 3).

2005;45(5):566–572.

26.National Transitions of Care Coalition. Transitions

of Care Measures, Paper by the NTOCC Measures

Work Group, 2008. http://www.ntocc.org/Portals/0/

TransitionsOfCare_Measures.pdf. Accessed March

20, 2012.

27.Surescripts. Walgreens and Surescripts improve

coordination of care by electronically delivering

immunization and patient summary records to

primary care providers. March 12, 2012. http://

www.surescripts.com/news-and-events/pressreleases/2012/march/312_walgreens.aspx. Accessed

March 20, 2012.

28.Millonig MK. Mapping the route to medication

therapy management documentation and billing

standardization and interoperabilility within the health

care system: meeting proceedings. J Am Pharm Assoc

(2003). 2009;49(3):372–382.

29.The Joint Commission. Safely implementing health

information and converging technologies. Sentinel

Event Alert, Issue 42, December 11, 2008. http://www.

jointcommission.org/sentinel_event_alert_issue_42_

safely_implementing_health_information_and_

converging_technologies/. Accessed March 20, 2012.

30.USP U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention. MEDMARX

2006 data report. www.usp.org/products/medMarx.

Accessed March 20, 2012.

31.Isaac T, Weissman JS, Davis RB, et al. Overrides of

medication alerts in ambulatory care. Arch Intern Med.

2009;169(3):305–311.

32.Wolfstadt JI, Gurwitz JH, Field TS, et al. The effect of

computerized physician order entry with clinical decision

support on the rates of adverse drug events: A systematic

review. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(4):451–458.

33.Bobb A, Gleason K, Husch M, Feinglass J, Yarnold PR,

Noskin GA. The epidemiology of prescribing errors:

The potential impact of computerized prescriber order

entry. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(7):785–792.

DrugTopics .c om

test questions

1.

Results from a study evaluating prescribing errors

during 1 week in 2002 at a 700-bed academic

medical center showed that:

a. Most prescribing errors occurred at

discharge from the hospital.

b. Of all verified prescribing errors, 64.4% were

likely to be prevented with a computerized

provider order entry (CPOE) system.

c. Prescribing errors are uncommon in a large

academic setting.

d. The errors rated clinically significant were

most frequently related to antihypertensive

medication.

2.The goals of “The Roadmap for Pharmacy Health

Information Technology Integration in U.S. Health

Care” include:

a. Ensure federal incentives for pharmacists

b. Ensure medication standards for hospital

formularies

c. Achieve unique pharmacy coding for

pharmacy-provided immunizations

d. Achieve recognition of pharmacists as

meaningful users of electronic health record

(EHR) quality measures

3.The 15 professional core objectives required for

Medicare and Medicaid incentives include:

a. Record smoking status for adults (aged 20

years or older) only

b. Record vital signs and chart changes for

children from newborn to 20 years

c. Use a CPOE system

d. Provide patients with paper and electronic

copies of their health information

4.According to Surescripts, what percentage

of community pharmacists in the United

States are connected for routing prescriptions

electronically?

a. 73%

b. 76%

c. 82%

d. 91%

5.Because of recent changes in Drug Enforcement

Agency regulations, which of the following is no

longer a barrier to electronic prescribing?

a. Short-cut features that automatically

complete information fields

b. Pharmacists’ investment in electronic

software

c. Manual prescription information entry

d. Prohibition against electronic prescribing for

controlled substances

6.The results of a review of the medical literature

to evaluate the effects of CPOE on adverse drug

events showed that:

a. CPOE with clinical decision support

contributed a statistically significant

decrease in adverse drug events (ADEs) in

50% of the studies.

b. Three studies reported a nonstatistically

significant reduction in ADE rates.

c. Four studies demonstrated no change in

ADE rates.

d. No study met the inclusion criteria of

computer system, drug categories, types of

ADEs, and clinical outcomes.

7.The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act,

which was signed into law in 2009, authorizes:

a. $10 billion designated to implement health

information technology (HIT) regional health

information exchange networks

b. As much as $6,750 over 6 years for eligible

pharmacists

c. $27 billion over 10 years designated in

Medicare and Medicaid incentive payments

for eligible providers who use EHRs and

demonstrate “meaningful use” of HIT

d. As much as $144,000 for eligible

physicians over a 5-year period through

Medicare

8.In February 2012, federal officials released the

stage 2 guidelines for meaningful use including:

a. Requiring physicians and hospitals to

significantly increase their use of electronic

health information

b. Meaningful usage requiring that at

least 80% of patients must have their

medications and laboratory tests ordered

electronically

c. Requirements for stage 2 meaningful use to

be in place immediately

d. Pharmacy HIT systems become

interoperable by 2014

9.The nation’s goal for EHRs is to reduce costs

through less paperwork, improved safety,

and reduced duplication of testing, and to

improve health by gathering a patient’s entire

health information in a single location. EHRs

accomplish this by:

a.Being “an electronic record of health-related

information on an individual that is created,

gathered, managed, and consulted by

authorized healthcare clinicians and staff.”

b.Being “an electronic record of individually

identifiable health information on an

individual that can be drawn from multiple

sources and that is managed, shared, and

controlled by and for the individual.”

c. Restricting data from certain defined sources

and health and medical entities.

d. Being generated by physicians, patients,

hospitals, pharmacies, and other sources

but initiated and managed by the patient.

10.In more than 100 interviews with physician

practices and pharmacies nationwide this past

year, researchers at the Center for Studying

Health System Change noted flaws and

inconsistencies concentrated in 3 critical areas

in e-prescriptions. These include:

a. New prescriptions

b. Volume of electronic prescriptions

c. Connectivity between physician offices and

mail-order pharmacies

d. Computerized entry of prescription

information by pharmacists

April 2012

Drug topics

53

caSe StudieS

Continuing Education

case a

A primary care physician (PCP) electronically prescribes 5 medications for a Medicare Part D patient post yearly physician visit.

Four of the medications were continued from the previous visit.

This patient qualifies for a yearly comprehensive medication review (CMR) as defined by the Part D plan’s medication therapy

management (MTM) program.

The pharmacist receives the electronic prescriptions, and the

pharmacy management system (PMS) alerts the pharmacist that

the patient’s prescription drug plan will authorize a CMR using the

National Council for Prescription Drug Programs (NCPDP) standardized transaction (an electronic transaction for a payer to request

MTM services from a provider). Mail and fax are other ways to

receive a CMR request. Under the Part D plan’s business agreement, the clinical pharmacist in charge of the pharmacy’s MTM

service programs messages the patient and the PCP that a CMR

is needed. The PMS adopted a pharmacist electronic health record

(EHR) functionality, and the PMS is certified for the meaningful use

of the EHR criteria.

Using the pharmacy’s e-prescribing network, the PMS queries the PCP’s EHR, the patient’s personal health record (PHR),

and the state health information exchange (HIE) for the patient’s

continuity-of-care documents (CCD), which contain allergies, chief

complaints, active medications list, diagnosis, family history, immunizations, functional status, social history, vital signs, laboratory

data, etc. The patient schedules a CMR with the clinical pharmacist. The result of the CMR is electronically exchanged with the

PCP’s EHR and the medication action plan is electronically sent

to the patient’s PHR.

1.

Which of the following statements is correct?

a. Only e-prescribing networks can electronically connect with PMS.

b. PMS can connect with e-prescribing networks and HIEs.

c. Pharmacists are not allowed to access patient information through an

HIE.

d. Only physicians can access patient information through an HIE.

2.

How is a request for a CMR transmitted?

a.

b.

c.

d.

3.

Electronically using an NCPDP standardized transaction

Fax

Mail

All of the above

electronic prescription for a Schedule C-II controlled substance

was transmitted to the patient’s local pharmacy using an eprescribing network. Using the pharmacist EHR, which does

not have to be confined to the four walls of a pharmacy, the

clinical pharmacist electronically queried the patient’s hospital

discharge summary and electronically coordinated a pain medication action plan with the PCP and the home healthcare nurse.

1.

a. Controlled substance prescriptions cannot be sent via e-prescribing.

b. Only Schedule C-II medications can be sent via e-prescribing.

c. Pharmacies can receive electronic prescriptions for controlled substances from a hospital.

d. All of the above.

2. . In which of the following situations can a pharmacist query a hospital’s

EHR?

a.

b.

c.

d.

3.

c. All of the above

d. None of the above

54

Drug topics

April 2012

The medication action plan should be discussed with which of the following

individuals:

b. Patient

c. Nurse

d. All of the above

case c

An elderly patient asks her local chain pharmacy about getting

her flu shot. The pharmacist is not familiar with this patient and

notices that the patient displays symptoms of mild confusion.

Using the PMS’s EHR, the pharmacist queries the PCP’s EHR

and the public health department for the patient’s immunization

history, allergy information, and other pertinent information in

the form of a CCD. The query indicates that the patient has no

known allergies, received a flu vaccine last year, and a pneumococcal immunization the previous year. The pharmacist administers the flu vaccines and electronically transmits the new flu

vaccine information to the PCP and the public health department.

1.

If a pharmacist is unfamiliar with a patient’s vaccination history, the

following may be conducted:

a.

b.

c.

d.

2.

Patient should be asked about their vaccination history.

Using a CCD, a pharmacist can query a PCP’s EHR.

Allergy information is available in a CCD.

All of the above

Which of the following information can be found in the CCD?

a. Immunization history

b. Allergy information

case B

A patient in a car accident and post hospital surgery was

discharged home with a broken arm and leg. The patient’s

discharge summary in the form of a CCD, which contains allergies, chief complaints, active medications list, diagnosis,

family history, immunizations, functional status, social history,

vital signs, laboratory data including electronic x-ray images,

was electronically transmitted to the PCP and home healthcare agency coordinating the patient’s rehabilitation therapy. An

Pharmacist working in a community pharmacy

Pharmacist working in a chain pharmacy

Pharmacist not working within the four walls of a pharmacy

All of the above

a. PCP

A PMS can query which of the following:

a. PCP’s EHR

b. Personal health records

Which of the following statements is correct?

3.

c. Active medications list

d. All of the above

Which of the following statements is correct?

a. Pharmacists providing immunizations should only electronically transmit

flu vaccine information to the PCP.

b. The public health department should not be notified of patient immunization updates.

c. Pharmacists providing immunizations should provide vaccine information to the patient’s PCP and the public health department.

d. None of the above

DrugTopics .c om