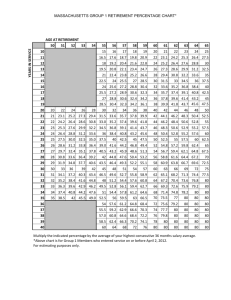

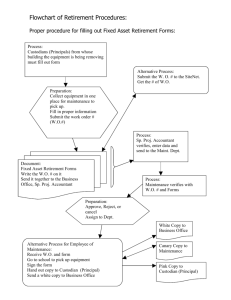

Self-management of career and retirement

advertisement