Voting Behaviour in Namibia

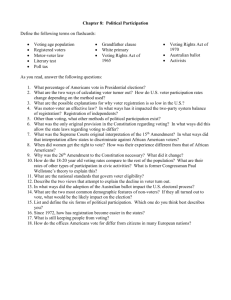

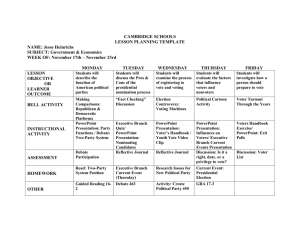

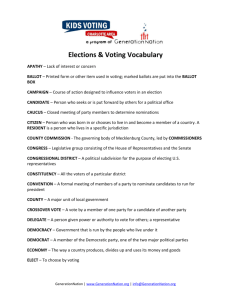

advertisement