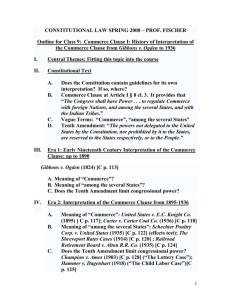

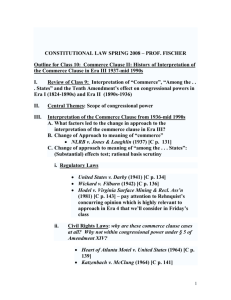

Federalism and Congressional Regulation of Commerce

advertisement