How Old is Old? - Detroit Institute of Arts

advertisement

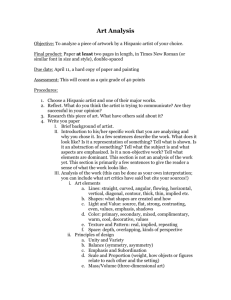

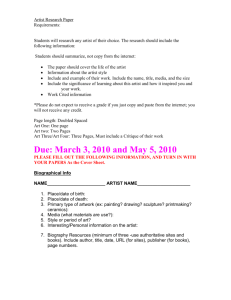

Student Exclusive HOW OLD IS OLD? You might think there’s a lot of old stu¼ at the Detroit Institute of Arts. But, this tour is about really old stu¼—hundreds, sometimes thousands of years old. The objects come from all over the world, and they’re located all over the museum. Hope you wore your walking shoes. Use the maps at the end of the guide to help you get around. Food forever Ancient Egyptians believed that a person’s soul lived on aªer death. Since food is pretty important for living, they made sure to include images of various cuisines in their tombs to nourish the soul. This guy, named Ka-aper, gets to have duck, bread, and a cut of meat. Extra bonus—the food’s not even moldy aªer four thousand years. Duck Meat Bread Check it out. There’s a computer station nearby where you can explore a really old scroll. Unknown artist, Egyptian; Relief of Ka-aper with O¼erings, 2565–2420 B.C.E.; limestone. Founders Society Purchase, Sarah Bacon Hill Fund —2— Can you find me? Here’s a clue: In the wild I grab flies with my tongue. Take a look around…keep looking…getting closer… eureka! You found me. I’m a golden frog, and I’m in a case with a bunch of other golden animals. An artist in Costa Rica made me for a chief over six hundred years ago. You may think frogs are wimpy, but the frog I’m based on had poison in its skin. By owning me, the chief let people know he was as tough as a poisonous frog. Check it out. Did you enjoy searching for the golden frog? Then, you’ll love Eye Spy. Throughout the museum you’ll see signs like the one shown here that give clues for finding objects in the galleries. Happy hunting. Unknown artist, Chiriqué culture, Costa Rica and Panama. Frog Ornament, 750–1400, gold. Bequest of Robert H. Tannahill —3— Spreading the power Ever heard of Alexander the Great? He was a king who ruled in ancient Greece more than two thousand years ago. He’s known for his enormous empire—he just kept making it bigger, and bigger, and bigger (use the globe nearby to see how big it got). There weren’t t.v.s or radios back then, so coins and statues were used to let everyone know just how important and powerful Alexander was. You might say it’s like seeing George Washington’s face on a quarter. Pick up the laminated sheet on the front of this case to learn more about the objects. Check it out. Down the hallway, you’ll find a case filled with metal helmets. Try the activity and see if you can guess how the helmets were used. Above leª: Unknown artist, Roman; Head of Alexander the Great as Hermanubis, 100–200 C.E.; marble. Giª of Madeline Verkinderin Above right: Unknown artist, Greek; Coin (tetradrachm) Depicting Alexander the Great, 323–281 B.C.E.; silver. City of Detroit Purchase —4— Light it up Before there were energy-saving light bulbs, there were lamps. Cool lamps, like this one. In order to keep their parties going well into the night, ancient Greeks and Romans used oil lamps to light up a room. This lamp was used by filling the base with olive oil and lighting a wick inserted through the man’s mouth. It probably looked like he was breathing fire. Check it out. Ancient Greeks and Romans liked to drink wine at their parties. Check out the nearby video to see how wine was mixed and served. Unknown artist, Roman; Lamp, 100–200 C.E.; bronze. Founders Society Purchase, with funds from Anne and Reginald Harnett —5— Where are my legs? No worries—the legs aren’t missing. The armor was only meant to cover the top half of the body. Around four hundred years ago, the grandson of Duke Cosimo I wore this armor during a sporting tournament. In front of an audience, he fought his opponent with wooden weapons over a waist-high railing. He didn’t need any leg protection, but he certainly needed plenty of upper body protection. The holes held another layer of metal to provide extra protection for the nose and chin. He fought with his right hand, so the right shoulder was made smaller than the leª for freer movement. Smooth edges guaranteed that a sword wouldn’t get caught on the armor. Extra metal helped protect the elbow joints. Check it out. Explore the timeline in this gallery to find out more about Duke Cosimo I and his family. Master Mariano, “The Armorer,” Italian; Boy’s Suit of Half-Armor (Corslet) for Cosimo II, about 1605; steel, partially purple-tinted with gold decoration. Giª of William Randolph Hearst Foundation —6— Go on in That’s right; this was part of an actual house called Whitby Hall. Step through the doors, and you’ll be transported back to 1754— the year the home was built. Sorr y! This wor k of art is tempo rarily o¼ view. This Philadephia residence once belonged to James Coultas, a wealthy merchant who wanted a place to entertain. Imagine the scene— women in fancy dresses, men sitting at a table playing cards, the sounds of laughing and the clinking of glasses. Not too shabby. The stairs, woodwork, and windows are from the original house. Unfortunately, you can’t go upstairs. But, there’s plenty to see on the first floor, so take a look around. Unknown artist, American; Whitby Hall, 1754. City of Detroit Purchase —7— Men with flowers That’s right. They’re holding flowers. But why? The small painting on the right shows a man from the 1400s following an old German tradition. By holding a carnation, he’s letting people know that he’s engaged or newly married. Five hundred years later, the artist Otto Dix decided to paint a picture of himself in the same way. Dix wasn’t engaged or married—he painted himself holding a flower because he wanted to imitate traditional German portraits. By presenting himself in a pose similar to the man on the right, Dix is showing his pride in his German heritage. Above leª: Otto Dix, German; Self-Portrait, 1912; oil on paper mounted on poplar panel. Giª of Robert H. Tannahill Above right: Michael Wohlgemut, German; A Young Man, 1486; oil on linden panel. Giª of Mr. and Mrs. Ernest Kanzler, in memory of Dr. and Mrs. Karl Kanzler —8— Lots and lots of bones OK. So, this is supposed to be a tour about old stu¼, and we’re in the contemporary galleries. Why? Well, the artist Nancy Graves created her sculpture by making copies of old camel leg bones. Imagine what camels’ legs look like when they move under the weight of those heavy humps. Each joint works together to keep the camel going forward. If you look closely at these bones, you’ll see that they look like they’re almost walking. That’s because the artist wanted to represent the movement of camels, animals that she loved to watch. Just for fun, see if you can count how many bones there are—try not to get dizzy. Nancy Graves, American; Variability of Similar Forms, 1970; steel, wax, marble, dust, acrylic, wood. Founders Society Purchase, W. Hawkins Ferry Fund, with funds from Joan and Armando Ortiz Foundation and Friends of Modern Art —9— 1st level —10— 2nd level Tell us what you think. • Did you find this guide useful? • What did you like the most? • What didn’t work so well? Your comments will help us improve guides for future visits. Email: guides@dia.org Cover: Unknown artist, Greek; Coin (tetradrachm) Depicting Alexander the Great, 323–281 B.C.E.; silver. City of Detroit Purchase —11—