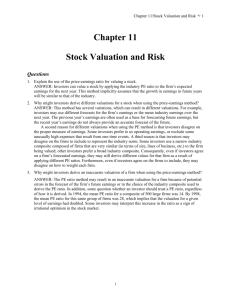

Stock Valuation: A Second Look

advertisement