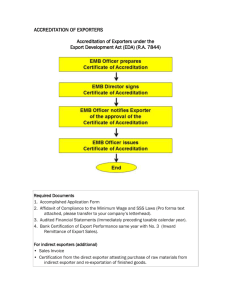

THE ROLE AND IMPORTANCE OF EXPORT CREDIT AGENCIES

advertisement