not only linnaeus

advertisement

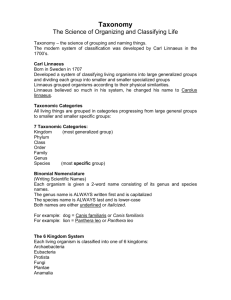

Sidan 1 av 6 UPPSALA UNIVERSITY: Dept of systematic biology Linnaeus’ Life and Sciences 7,5 p Web course autumn 2008 NOT ONLY LINNAEUS who influenced 2009-01-12 Birgitta Hahn Supervisor: Mariette Manktelow Sidan 2 av 6 NOT ONLY LINNAEUS Who influenced Reading about Linnaeus life and his classification of plants in the eighteenth century makes me curious. While still a young boy Linnaeus read many books on botany that might have inspired him and his own scientific work. Who influenced him to his sexual classification? What characteristics of style during the seventeenth and eighteenth century were prevalent? In this essay, I will start with a brief review of the history of the most influential classifiers of flowering plants from Antiques to 1700th century in Western world.1 Then I will present some later naturalists more closely and see how they might have influenced Linnaeus. Aristotle’s pupil THEOPHRASTUS (372-287 BC) was called the father of Botany by Linnaeus.2 He was the first one who made attempts to develop basic theoretical concepts about plants. He discussed for instance the principles of plant morphology and classification and he established a descriptive terminology. From this he arranged the 400 plants known to him into four groups: trees, bushes, shrubs and herbals. These groups had subdivisions. His classifying system was still used by naturalists in the seventeenth century! In the Roman Empire the approach to botany made up by Theophrastus got lost and the interest for plants was limited to how to use them medically.3 In the army of Nero there was a physician DIOSCORIDES (40-90 AC). In campaigns he saw much illness and he collected and identified about 500 medical species. In the book Matera Medica he described these very closely, origin, medical use and how to prepare medicals out of them. His principle of division was their medical property and he presented them in alphabetic order. For 1500 years these descriptions by Dioscorides were the authority and base for medical career. During the Middle Age, monasteries kept the knowledge of cultivated and medical plants. In the Age of Renaissance, the interest for the Antique woke up and the principles of Theophrastus were rediscovered and gradually his theoretical thoughts influenced botany.4 Universities were opened and later in the 1600th century Botanical Gardens. The main purpose of these gardens was for medical studies. The exploration of parts 1 Botany On Line sept. 2008. http://www.biologie.uni-hamburg.de/b-online/e01/01a.htm 2 Morton A.G.1981. History of Botanical Science.Acad. Press Inc.(London) Ltd. p 43 3 ibid. p 82-83 4 ibid. p 121 Sidan 3 av 6 of the New World brought a large number of new plants into the gardens. Luca Ghini (1490-155) the founder of the Pisa Garden was the first to use a plant press and a herbarium. Around this time, botany became a distinguished subject at the university. The invention of the printing press in 1446 made the circulation of information easier. Many herbal books – often very lavishly illustrated - got printed by naturalists Later they were shown honour when names were given to plant genera, for instance Brunfelsia (Otto Brunfels 1488-1534 CH), Fuchsia (Leonarth Fuchs 1501-1566 D) Dalechampsia (Jaque Dalechamp 1513-1588 F), Gesneria (Conrad Gesner 1516-1565 CH) etc. Linnaeus called these men the Herbalists in Fundamenta Botanica 1746 From the 1600th century A. Caesalpino and C. Bauhin have to be mentioned: CAESALPINO (1519–1603) an Italian botanist, was a pupil to Ghini and became supervisor of the Botanical Garden at Pisa University after him. He was well acquainted with Greek philosophy and science and expressed acknowledgements to Theophrastus as the inspirer of his own theoretical thoughts. In his main work "De plantis" (Of Plants) in 1583 Caesalpino present a classifying system based on the morphology of seeds and fruits instead of medical use and alphabetic order. He thought colour, scent and taste to be of no importance and recommended to pay no attention to them. However, he could not escape from the division made by Theophrastus. Linnaeus wrote about Caesalpino that he was the first real classifier and the first Fructist as he used characters of fructifications as basis. 5 BAUHIN (1560–1624) was a Swiss botanist who described over 6000 plants in Pinax theatri botanici" (The Survey of Plants)" 1623, a huge work in which he collected all synonymous plant names from antiquity to his own time6. Linnaeus mentioned him as a synonym specialist in Fundamenta Botanica §39. When classifying plants Bauhin like Caesalpino still used the traditional groups of Theophrastus. Every specie got a name and he introduced many names of genera that later were adopted by Linnaeus. In Bauhin´s nomenclature there are as few words as possible; in many case a single word was sufficient as a description- a diagnostic word rather than a name. That gave an appearance of a two-part name7. J. JUNGIUS (1587-1657) was a philosopher and mathematician born in Lübeck, studied medicine in Padua and later working in Hamburg. For Botany, I can see three notable ideas.8 First, he expected that conclusions should be drawn from experiments. 5 Nynäs C. 2007. Carl von Linné. Om Botanikens grunder. Ett 1700-talsmanuskript sammanställt av Lars Bergqvist. Atlantis. Stockholm. Fundamenta Botanica § 28,54 6 http://edb.kulib.kyoto-u.ac.jp/exhibit-e/b07/b07cont.html. Jan 2nd 2009 7 The History of Taxonomy 1583-1690. http://www.bihrmann.com/caudiciforms/DIV/hist1.asp. Oct. 2008 8 Botany On Line oct. 2008. http://www.biologie.uni-hamburg.de/b-online/e01/01e.htm#jungius Sidan 4 av 6 Second, he pointed out that all parts of plants, which were of the same nature should bear the same names even if they might have different shapes. For example: a leaf could be round, lobed etc and still it is a leaf. The whole terminology bases on this principle. He discussed leaves, leafstalk and their attachments, flowers, fruits and seeds, which were defined by their topological interrelations within the plant body. Third, he found it to be logically correct that exactly defined terms, just like numbers, had to be reliable and unalterable value. Jungius refined and extended the concept of plant morphology derived from Theophrastus and Caesalpino. As he was not a botanist he did not create an own classification system, but he criticised existing views and proposed a comprehensive terminology to describe the forms of all parts of the plant. He also had a real insight into the grouping of plants according to the morphology of their flowers and he gave name to the groups Compositae, Labiatae and Leguminosae! He rejected Theophrastus categories of trees, bushes, shrubs and herbs. Jungius ideas was published in two works: Isagoge Phytoscopia (“A guide to examining plants)” and Doxosopiae Physicae Minores “(Brief investigations of plants)”. These were edited and published by two former students after his dead in 1679 and 1662 respectively but manuscript copies circulated earlier. Linnaeus referred to Isagoge in his works, i.e. Fundamenta Botanica 1748. Goethe said that if the ideas of Jungius were accepted and used sooner, the advantage of human knowledge might have been hastened by a century9. J. RAY (RAJUS)10 (1627 - 1705) from England was a naturalist, who as early as 1660 read Jungius and accepted his morphological system and terminology almost entirely. Ray made up rules to be observed in classification: 1. Names should not be changed to avoid confusion and errors. 2. Characteristics have to be exactly and distinctively defined which means that those basing on relative relations like heights are not to be used. 3. The characteristics should easily be detected by everybody. 4. Groups accepted by almost all botanists have to remain. 5. It has to be taken care, that related plants should be united; unnatural ones and those that are different should not be united. 6. The number of characteristics to make a reliable classification must not increase without necessity, only as many as necessary shall be used. Based on these rules, he tried to make wider relationships (families, genera). Like Caesalpino Ray argued that it was not reliable to use only one or two characters as 9 Guthrie D. 1959. Joachim Junge (1587-1657) A Forgotten Genius 23,. Nature 183:, 1435-36 10 Morton A.J. pp 195 Sidan 5 av 6 basis in classifying. Linnaeus often mentioned Ray and Jungius in his works, so these men ought to be well known for him. Ray also made experiments on seed germination and from these he drew the conclusion that seed plants could be divided in Dicotyledones and Monocotyledones. This division was soon generally accepted. Illogical did Ray still adhered to the division between of wooden and herbaceous plants. When Linnaeus was 19 years old and studied in Växjö, Dr Rothman made an essay about the sexuality of plants known to him11. That text must have impressed much upon Linnaeus. The author was S. VAILLANT (1669-1722) from France and his essay ”Discours sur la structure des fleurs” (About structures of Herbaceous Plants) was from a speech he held in 1717 in which he shocked his contemporaries by he comparing stamen to penis of animals. Vaillant referred to the German R.J. CAMERARIUS (1665-1722), who in dioecious plants had found that the removal of stamens from male plants either greatly reduced or eliminated fertility12 and that female plants grown with no male plants anywhere near produced fruits without embryos. In his field experiments species of Morus and Mercurialis were among those plants he used. He assumed that in cases when stamens and pistils are not close to each other, pollen must transfer to pistils by some means. While Vaillant compared pistils and stamens to sexual organs, Linnaeus, 22 years old compared them to women and men in his Praeludia Sponsaliorum Plantarum (1929). In this text, he referred to Vaillant but not to Camerarius. However, he described the experiment with removal of testicolus in § XXVI and he attached an illustration of Mercurialis. In a later work, Sponsalia Plantarum (1746)14, Linnaeus mentions the name of Camerarius and even others who had contributed to the knowledge about sex among plants. According to Th. Fries15, Linnaeus was criticised in his way of standing out as being the only originator of that knowledge and by mentioning these persons the accusations could end. This resembles Linnaeus behaviour not giving acknowledgements to the illustrator Ehret in his Systema Naturae.14 (It is interesting to note that on the 11 Frängsmyr T., Ed.1983. Linnaeus: The man and his work. Berkeley &Los Angeles, CA, Univ. of California Press. G. Eriksson. Linnaeus the Botanist. pp 6312 Zarsky V.,Tupy J. 1995.A Missed Anniversary: 300 Years after Jakob Camerarius ”De sexu plantarum epistola”. Sex Plant Reproduction 8:375-376 14 Kungl. Svenska Vetenskapsakademin. Ed. 1908. Almqvist och Wiksell Boktryckeri AB. Uppsala Linnaeus C.v. Skrifter IV. Valda smärre skrifter af botaniskt innehåll 1.: Praeludia Sponsaliorum and Sponsalia Plantarum. Uppsala 1729 resp. 1746. 15 14 ibid. Fries Th. In Noter till Sponsalia Plantarum p 47 Blunt W. 2004 The Compleat Naturalist-A Life of Linnaeus. Frances Lincoln Limited, London. p106 Sidan 6 av 6 Swedish one hundred-crown bill of today there is a figure of Mercurialis taken from Sponsalia Plantarum) In Sweden by the time of Linnaeus there was a common pedagogical principle of the importance to order and classify. The book Orbis Sensualium Pictus written by J.A. Comenius (1592-1670) spread this principle. The English philosopher F. Bacon (15611626), the profounder of experimental science, also demanded system and order. We can see the impact on the architecture of the botanical gardens and in the outlook of the popular cabinets of naturalia from that time. Linnaeus was enthusiastic in ordering. He ordered everything, everything in his seeking for the right method to get to know all created plant species. Linnaeus cited Bacon in the preface of Fundamenta Botanica 1748. In this essay I have tried to show that Linnaeus was not the only one on the arena. The progress from Theophrastus via Caesalpino to Jungius and Ray in their thoughts of a distinct terminology in order to classify in a proper way is stressed. Linnaeus fulfilled these thoughts. Bauhin facilitated Linnaeus work in giving him the synonyms and maybe inspired him giving shorter names to the plants. Dioscorides work about medical plants led to botanical gardens that primarily were used for medical studies, which Linnaeus went into. As long as there was a limited number of known plants the dividing of plants according to Theophrastus was enough, but with increasing number of plants the demand of a good classifying system grew. Caesalpino made a system based upon the fructification. Ray used the morphology of flowers and his division according to cotyledons became a basic feature of the classification of flowering plants. There were also others, not mentioned here, who made their systems. Valliant’s essay about sexual organs in the flowers together with Jungius suggestion to use numbers as unalterable values could well have inspired Linnaeus to use the numbers of stamens and pistils in his system presented in Systema Naturae. It is not easy to directly see who influenced Linnaeus by reading i.e. Fundamenta Botanica. His way of expressing his ideas in aphorisms hinders to see the connection between his own and his predecessors’ thoughts. In §31 he wrote: (my own translation) “The sexualists, like me, divide on the basis of sex. d) Sexualists have made their system after sexuality or stamens and pistils. When Linnaeus started to examine herbals he found sexuality to be absolutely right; and that no method have more Genera beneath. Linnaei method can be seen in Syst. Nat Gen. Plant. Flora Svec. etc.” There is no explanation why he thought it was the absolutely right method. He really was a man with great self-confidence.