Resources for Cultural and Linguistic Services

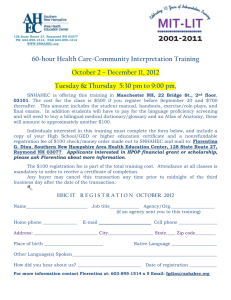

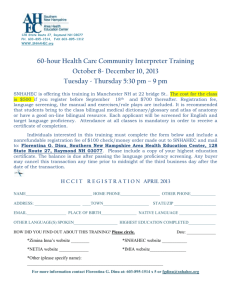

advertisement